Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

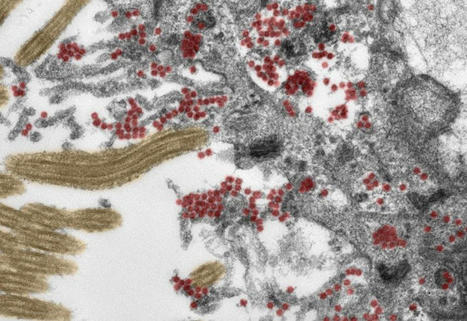

New research helps explain why long COVID can occur in people who had mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 cases. The coronavirus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, can spread within days from the airways to the heart, brain and almost every organ system in the body, where it may persist for months, a study found. In what they describe as the most comprehensive analysis to date of the virus’s distribution and persistence in the body and brain, scientists at the U.S. National Institutes of Health said they found the pathogen is capable of replicating in human cells well beyond the respiratory tract. The results, released online Saturday in a manuscript under review for publication in the journal Nature, point to delayed viral clearance as a potential contributor to the persistent symptoms wracking so-called long COVID sufferers. Understanding the mechanisms by which the virus persists, along with the body’s response to any viral reservoir, promises to help improve care for those afflicted, the authors said. “This is remarkably important work,” said Ziyad Al-Aly, director of the clinical epidemiology center at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System in Missouri, who has led separate studies into the long-term effects of COVID-19. “For a long time now, we have been scratching our heads and asking why long COVID seems to affect so many organ systems. This paper sheds some light, and may help explain why long COVID can occur even in people who had mild or asymptomatic acute disease.” The findings haven’t yet been reviewed by independent scientists, and are mostly based on data gathered from fatal COVID cases, not patients with long COVID or “post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2,” as it’s also called. Contentious Findings The coronavirus’s propensity to infect cells outside the airways and lungs is contested, with numerous studies providing evidence for and against the possibility. The research undertaken at the NIH in Bethesda, Maryland, is based on extensive sampling and analysis of tissues taken during autopsies on 44 patients who died after contracting the coronavirus during the first year of the pandemic in the U.S. The burden of infection outside the respiratory tract and time to viral clearance isn’t well characterized, particularly in the brain, wrote Daniel Chertow, who runs the NIH’s emerging pathogens section, and his colleagues. The group detected persistent SARS-CoV-2 RNA in multiple parts of the body, including regions throughout the brain, for as long as 230 days following symptom onset. This may represent infection with defective virus, which has been described in persistent infection with the measles virus, they said. In contrast to other COVID autopsy research, the NIH team’s post-mortem tissue collection was more comprehensive and typically occurred within about a day of the patient’s death. Culturing Coronavirus The NIH researchers also used a variety of tissue preservation techniques to detect and quantify viral levels, as well as grow the virus collected from multiple tissues, including lung, heart, small intestine and adrenal gland from deceased COVID patients during their first week of illness. “Our results collectively show that while the highest burden of SARS-CoV-2 is in the airways and lung, the virus can disseminate early during infection and infect cells throughout the entire body, including widely throughout the brain,” the authors said. The researchers posit that infection of the pulmonary system may result in an early “viremic” phase, in which the virus is present in the bloodstream and is seeded throughout the body, including across the blood-brain barrier, even in patients experiencing mild or no symptoms. One patient in the autopsy study was a juvenile who likely died from unrelated seizure complications, suggesting infected children without severe COVID-19 can also experience systemic infection, they said. Immune Response The less-efficient viral clearance in tissues outside the pulmonary system may be related to a weak immune response outside the respiratory tract, the authors said. SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in the brains of all six autopsy patients who died more than a month after developing symptoms, and across most locations evaluated in the brain in five, including one patient who died 230 days after symptom onset. The focus on multiple brain areas is especially helpful, said Al-Aly at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System. “It can help us understand the neurocognitive decline or ‘brain fog’ and other neuropsychiatric manifestations of long COVID,” he said. “We need to start thinking of SARS-CoV-2 as a systemic virus that may clear in some people, but in others may persist for weeks or months and produce long COVID -- a multifaceted systemic disorder.” Preprint (Dec. 20, 2021) of the research cited available at: https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-1139035/v1_covered.pdf?c=1640020576

Via Juan Lama

Anxiety disorders, depression, and insomnia were the most common disorders reported after people developed the disease. People across the world have been experiencing a higher level of stress due to the pandemic, but researchers at the University of Oxford have found the link between COVID-19 and mental illness may be more direct than initially thought. A study published in The Lancet found one in five people diagnosed with COVID-19 developed some form of mental illness 90 days after being diagnosed with the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. The patients had not had mental health disorders prior to contracting the coronavirus. The study analyzed data from 69 million people in the United States, 62,000 of whom were COVID-19 patients. Anxiety disorders, depression, and insomnia were the most common disorders reported after people developed the disease. The virus attacks the central nervous system The authors of the study said they were unsure why the virus would increase mental health problems in people with otherwise no history of mental illness, and that more research is needed.Simon Wessely, a psychiatry professor at King's College London who was not involved in the study, told Reuters the link between mental health and COVID-19 might be explained by how COVID-19 attacks the central nervous system. Michael Bloomfield, a consultant psychiatrist at University College London, added the effects of the coronavirus coupled with the external stress of the pandemic might be why this correlation between COVID-19 and mental illness exists. "This is likely due to a combination of the psychological stressors associated with this particular pandemic and the physical effects of the illness," Bloomfield told Reuters. Previous research found COVID-19 can lead to lasting cognitive effects Mental health consequences aren't the only neurological symptoms exhibited by COVID-19 patients. A study published in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology in October found 80% of people hospitalized with COVID-19 had neurological symptoms like muscle aches, dizziness, and confusion. It also found one-third of COVID-19 patients sustained encephalopathy, a broad term for damage to the brain. The study published in The Lancet found that in addition to mental illness, people over the age of 65 who developed COVID-19 were more likely to receive their first diagnosis of dementia, a neurological disorder, within 90 days. People with previous mental illness were 65% more likely to develop COVID-19 The study authors said they were also surprised to find how vulnerable mental illness made people to contracting COVID-19. People who had mental health conditions prior to the pandemic were 65% more likely to develop COVID-19. "This is important when we think of the people at risk which should receive the vaccine first. It might be that a history of mental illness should be considered in this decision," Dr. Maxime Taquet, lead author of the study, told Insider. Study cited published in The Lancet (Nov. 9, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4

Via Juan Lama

autoantibodies in neurological forms

Few detailed investigations of neurologic complications in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection have been conducted. We describe 3 patients with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease who showed development of encephalopathy and encephalitis. Neuroimaging showed nonenhancing unilateral, bilateral, and midline changes not readily attributable to vascular causes. All 3 patients had increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of anti-S1 IgM. One patient who died also had increased levels of anti–envelope protein IgM. CSF analysis also showed markedly increased levels of interleukin (IL) 6, IL-8, and IL-10, but severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 was not identified in any CSF sample. These changes provide evidence of CSF periinfectious/postinfectious inflammatory changes during coronavirus disease with neurologic complications.

|

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19 enters the brain via neurons in the olfactory mucosa.

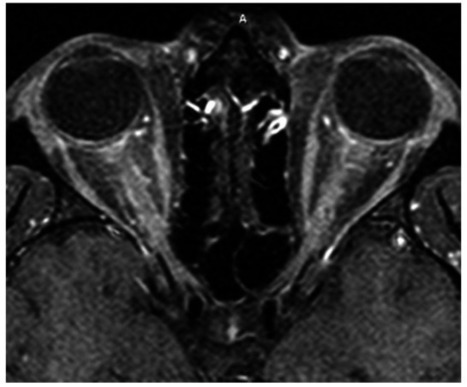

The outbreak of the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the etiological agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), was first reported in late December 2019 in Wuhan, China, (1) and has since transformed into a rapidly evolving global pandemic. As the number of infections grows, so does our knowledge of possible clinical symptoms, signs, and manifestations. The coronavirus family of viruses, including SARS coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), is most well known for causing respiratory syndromes, with severe cases leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). There is an ever-growing body of literature describing other organs as sites of damage caused by this family of viruses, including cardiac (2), gastrointestinal (3), neurological (4–11), and ophthalmic (12–14) involvement. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, and other coronaviruses has been described, and it has been hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 may be able to directly access the central nervous system (CNS) through a transsynaptic route given considerable sequence homology, and that this may be a mechanism of respiratory failure in COVID-19 (5). Moreover, a recent report of SARS-CoV-2 preceding antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (9) leading to thrombus formation underscores the potential for this infectious agent to trigger autoantibody production. Additional reports of COVID-19 presenting as Miller Fisher syndrome (10), Guillain–Barré syndrome (11), and Kawasaki syndrome (13) offer specific examples of this virus's ability to dysregulate the immune system. Herein, we describe a case of a young man presenting with bilateral severe optic neuritis and myelitis, determined to be simultaneously SARS-CoV-2 and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) IgG antibody positive. We believe this is a unique neuro-ophthalmic manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 and the first such case to be reported in the literature. This report adheres to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient data were obtained through inpatient and outpatient encounters and medical records at Keck Medical Center, University of Southern California. Informed consent was obtained verbally as well as part of the patient agreement for use of clinical information and photographs for educational purposes. A 26-year-old Hispanic man presented for evaluation of bilateral, subacute, sequential vision loss first affecting the left eye, then the right eye 3 days later. Pain with eye movements preceded the vision symptoms in each eye. An ophthalmologist noted disc edema and urgently referred him to our practice for further evaluation. On review of systems, he reported a few days of progressive dry cough before the onset of eye pain and vision loss. He also endorsed numbness on the soles of his feet and neck discomfort with forward flexion but denied shooting, electric-like pain. He denied fevers, chills, sweats, shortness of breath, rhinorrhea, chest pain, or changes in taste or smell. There were no recent headaches, weakness, imbalance, bowel or bladder dysfunction, and cognitive or mood changes. He further denied personal or family history of demyelinating or autoimmune disorders. He had 4 dogs at home and denied cat exposure. He denied recent travel or sick contacts. Our examination revealed hand motion vision in the right eye and 20/250 in the left eye, with a right relative afferent pupillary defect. Ocular motor and remaining cranial nerve examinations were normal. Dilated fundus examination revealed bilateral disc edema and venous congestion, with retinal perivenous hemorrhages in the right eye (Fig. (Fig.11). His clinical picture of severe sequential bilateral optic neuritis with disc edema was highly suspicious for MOG antibody disease, but the broader differential diagnosis also included infectious, inflammatory, and infiltrative processes. Our initial workup included testing for QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus, rapid plasma reagin, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and aquaporin-4 (AQP4) and MOG-IgG cell-based assays. Given our evolving understanding of the heterogenous clinical presentations of this novel pathogen, and the potential for this presentation to be the result of a secondary immune response, we felt that SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was justified, despite our patient demonstrating only one well-described clinical symptom of COVID-19 (dry cough). Within 24 hours, SARS-CoV-2 testing from nasal and oropharyngeal swabs processed by the Roche Cobas 6800 SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR system (Roche Molecular 66 Systems, Branchburg, NJ) returned positive. He was admitted to Keck Hospital for completion of the workup, multidisciplinary management, and careful clinical monitoring. MRI of the brain and orbits with and without contrast revealed avid, uniform enhancement and thickening of both optic nerves extending from the globe to their intracranial prechiasmal segments, without overt involvement of the chiasm (Fig. (Fig.2).2). One small nonenhancing, nonspecific periventricular T2 hyperintensity was present, adjacent to the occipital horn of the right lateral ventricle. MRI of the spine with and without contrast was notable for patchy T2 hyperintensities in the lower cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord associated with mild central thickening and gadolinium enhancement (Fig. (Fig.3).3). Lumbar puncture revealed a normal opening pressure of 12.7 cm, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein 31, and glucose 57 (within normal limits). CSF white blood cells were elevated at 55 cells/μL (normal < 5) with 100% mononuclear cells. Identical oligoclonal bands were present in both serum and CSF, but none were unique to the CSF, consistent with a systemic inflammatory response. CSF bacterial cultures and SARS-CoV-2 RNA PCR were negative. Serum AQP4 antibodies were not detected; however, MOG-IgG was highly positive at a titer of 1:1,000 (Mayo Clinical Laboratories, Mayo, Rochester, MN). Immediately after the lumbar puncture, one gram of intravenous methylprednisolone was administered daily for 5 days, followed by an oral prednisone taper. Visual acuity improved rapidly and incrementally to the level of 20/50 in each eye by the time of discharge on the seventh day after admission. His vitals and pulmonary function remained completely normal throughout his hospital course, and he displayed no additional signs or symptoms of COVID-19. The remainder of his infectious and inflammatory bloodwork returned unremarkable. Outpatient follow-up 3 weeks later revealed 20/30 vision in both eyes and complete resolution of disc edema and retinal findings. Our case of a young Hispanic man with severe bilateral sequential vision loss associated with optic disc edema, retinal venous congestion, long-segment bilateral optic neuritis, and myelitis is fairly classic for MOG-IgG–mediated demyelinating disease (15). MOG-IgG antibodies target the MOG uniquely expressed on oligodendrocytes. It is thought to serve as a cellular receptor, adhesion molecule, or regulator of microtubule stability (16,17). MOG antibodies can circulate freely but do not exhibit a pathologic effect, unless they gain access to the CNS through disruption of the blood–brain barrier, typically as a result of inflammation or infection (18). Once access to the CNS is gained, pathology is mediated by T cells and complement-fixing antibodies, leading to the varied clinical features associated with MOG antibody–mediated CNS disease, including optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, encephalitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) (15–17). An etiologic link between parainfectious or postinfectious demyelinating syndromes and a prodromal viral illness has long been considered and is now well established. The earliest such report may be from 1790 describing a 23-year-old woman with weakness and bladder dysfunction occurring 1 week after a measles rash (19). Leake et al. (20) noted that 93% of patients with ADEM in their series had a history of viral illness within 21 days of the onset of neurological symptoms. The prevailing mechanism of injury is felt to involve molecular mimicry, where a variety of potential viral antigens trigger an immune response directed toward endogenous CNS myelin proteins, including MOG (21). Recent literature has focused on the considerable phenotypic, epidemiologic, and immunologic overlap between ADEM and MOG-IgG–mediated CNS disease. As many as 50% of patients with ADEM have been reported to test positive for serum MOG antibodies, and this proportion may be even higher in ADEM patients with recurrent polyphasic disease (22). Hence, there is a large body of established literature linking viral pathogens and the development of ADEM and MOG antibody–mediated CNS injury (23–26). Pertinent to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, in 2004, Yeh et al. (27) described a patient with ADEM associated with a human coronavirus (HCoV-OC43) detected in his serum and CSF samples, and murine hepatitis coronavirus has been implicated in CNS demyelinating disease for over 2 decades (28). SARS-CoV-2 has demonstrated its ability to incite a profound host immune response. The most established immunological manifestation is ARDS, occurring in up to 29% of cases (29). Multiple groups have begun to characterize its complex immunological basis, involving a variety of cytokines and inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein, D-dimer, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, granulocyte colony stimulating factor, IP10, MCP1, MIP1A, and TNFα, particularly in patients with more severe COVID-19 disease. Our report, along with the aforementioned recent reports of antiphospholipid antibody, Kawasaki, Miller Fisher, and Guillain–Barré syndromes in association with SARS-CoV-2, highlights the potential for this infectious agent to trigger autoantibody production, which could have a broad array of clinical manifestations depending on the target organ of the autoantibodies. Interestingly, our patient did not have ARDS or some other manifestation of severe COVID-19 clinically, suggesting that novel autoantibody syndromes may need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of mild COVID-19 when clinically appropriate. We recognize that CSF SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing has not been validated, and its sensitivity and specificity in clinical settings are not currently known. As such, the negative CSF SARS-CoV-2 PCR result does not rule out direct CNS infection in this case. Although neurotropism is certainly plausible, we believe a secondary, immune-based pathogenesis triggered by SARS-CoV-2 is far more likely in this case. The clinical symptoms and signs, serum and CSF results, radiological findings, and dramatic treatment response to steroids all firmly support an inflammatory disorder and are quite characteristic of MOG-IgG–mediated CNS disease. The established connection between a viral prodrome and MOG antibody disease, taken together with the clear temporal sequence between our patient's SARS-CoV-2 infection, neuroimmunological presentation, and MOG-IgG seropositivity, provides robust evidence supporting a causal link between SARS-CoV-2 infection and MOG-IgG–mediated CNS demyelination. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case to establish concurrent SARS-CoV-2 infection and MOG-IgG antibody–mediated CNS disease. As a global community, we continue to learn in real time about the myriad of possible clinical manifestations comprising COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 infection should be considered in any patient presenting with new neuroimmunological manifestations potentially consistent with MOG-IgG–mediated disease. Failure to recognize this potential connection and immunological basis for devastating vision loss in this context may lead to a number of adverse outcomes. These include delayed diagnosis of the underlying SARS-CoV-2 infection, systemic compromise after treatment with high-dose corticosteroids (30) in the presence of an unrecognized SARS-CoV-2 infection, or a potential delay in initiation or withholding of high-dose corticosteroids, if the secondary autoantibody response is unrecognized and the clinical presentation is presumed secondary to direct viral injury. STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP Category 1: a. Conception and design: S. Zhou, E. C. Jones-Lopez, D. J. Soneji, C. J. Azevedo, and V. R. Patel; b. Acquisition of data: S. Zhou, E. C. Jones-Lopez, D. J. Soneji, C. J. Azevedo, and V. R. Patel; c. Analysis and interpretation of data: S. Zhou, E. C. Jones-Lopez, D. J. Soneji, C. J. Azevedo, and V. R. Patel. Category 2: a. Drafting the manuscript: S. Zhou, C. J. Azevedo, and V. R. Patel; b. Revising it for intellectual content: S. Zhou, E. C. Jones-Lopez, D. J. Soneji, C. J. Azevedo, and V. R. Patel. Category 3: a. Final approval of the completed manuscript: S. Zhou, E. C. Jones-Lopez, D. J. Soneji, C. J. Azevedo, and V. R. Patel.

“I tell the same stories repeatedly; I forget words I know.”

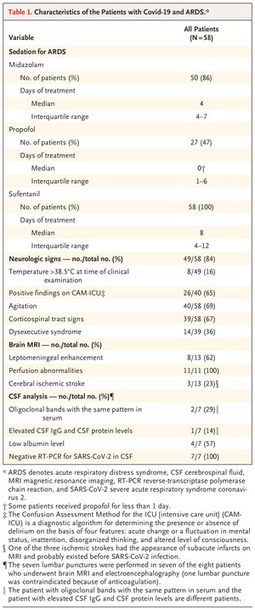

Neurologic Features in SARS-CoV-2 Infection In a consecutive series of 64 patients with Covid-19 and ARDS, 58 of whom underwent neurologic examination, severe agitation and corticospinal sign

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Magic Mushroom Compound Called Psilocybin May Help Treat DepressionThe psychedelic substance found in magic mushrooms, also known as shrooms, can relieve symptoms in people with major depressive disorder, according to a new studyTrusted Source.

While additional research is needed, this study shows the clinical potential of psilocybin, particularly for treating depression that’s resistant to other therapies.

The study was published on November 4 in JAMA Psychiatry.

“This is an extremely important study that advances the study of psychedelics and mental health, but more importantly, offers a new and novel treatment for major depressive disorder,” said Dr. Rakesh Jetly, chief medical officer at Mydecine, who wasn’t involved in the new study.

Twenty-four people completed the study, which involved receiving two doses of psilocybin along with supportive psychotherapy.

Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers reported that the participant’s depressive symptoms improved rapidly, with over two-thirds responding well to the treatment.

Four weeks after psilocybin treatment, over half of the participants met the criteria for remission of their depression.