Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Federal public health officials are turning to wastewater surveillance to help fill in the gaps in efforts to track H5N1 bird flu outbreaks in dairy cows. R eluctance among dairy farmers to report H5N1 bird flu outbreaks within their herds or allow testing of their workers has made it difficult to keep up with the virus’s rapid spread, prompting federal public health officials to look to wastewater to help fill in the gaps. On Tuesday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is expected to unveil a public dashboard tracking influenza A viruses in sewage that the agency has been collecting from 600 wastewater treatment sites around the country since last fall. The testing is not H5N1-specific; H5N1 belongs to the large influenza A family of viruses, as do two of the viruses that regularly sicken people during flu season. But flu viruses that cause human disease circulate at very low levels during the summer months. So the presence of high levels of influenza A in wastewater from now through the end of the summer could be a reliable indicator that something unusual is going on in a particular area. Wastewater monitoring, at least at this stage, cannot discern the sources — be they from dairy cattle, run-off from dairy processors, or human infections — of any viral genetic fragments found in sewage, although the agency is working on having more capability to do so in the future. CDC wastewater team lead Amy Kirby told STAT that starting around late March or early April, some wastewater collection sites started to notice unusual increases in influenza A virus in their samplings. Those readings stood out because by the last week of March, data the CDC tracks on the percentage of people seeking medical care for influenza-like illnesses suggested that the 2023-2024 flu season was effectively over. The increases were very site-specific, she said, and were not reflected in other areas. In fact, she called it “a very limited phenomenon. … The vast majority of our sites are not seeing this.” To date there has been little information in the public sphere about where infected cattle herds have been located. When the U.S. Department of Agriculture announces positive test results, it merely names the state in which the herd was located when the testing took place. Last week, the USDA reported that six additional herds — in Michigan, Idaho, and Colorado — had tested positive for H5N1, bringing the total to 42....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The avian influenza virus that has been infecting dairy cows and spreading alarm in the United States was expected to reach Germany this week. But that’s actually good news. A shipment of samples of the H5N1 virus from Cornell University virologist Diego Diel is destined for the Federal Research Institute for Animal Health in Riems, which has one of the rare high-security labs worldwide that are equipped to handle such dangerous pathogens in cattle and other large animals. There, veterinarian Martin Beer will use the samples to infect dairy cows, in search of a fuller picture of the threat the virus poses, to both cattle and people, than researchers have been able to glean from spotty data collected in the field. Six weeks into the outbreak that has spread to farms in nine U.S. states, the flow of data from those locations remains limited as public health officials sort out authorities and some farms resist oversight. “It’s incredibly difficult to get the right sample sets off the infected farms,” says Richard Webby, an avian influenza researcher at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. “It’s clearly a barrier to understanding what’s going on. … That’s why these experimental infections of cows are really going to be super informative.”

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Sporadic human infections with highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) virus, with a wide spectrum of clinical severity and a cumulative case fatality of more than 50%, have been reported in 23 countries over more than 20 years. HPAI A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b viruses have spread widely among wild birds worldwide since 2020–2021, resulting in outbreaks in poultry and other animals. Recently, HPAI A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b viruses were identified in dairy cows, and in unpasteurized milk samples, in multiple U.S. states. We report a case of HPAI A(H5N1) virus infection in a dairy farm worker in Texas. In late March 2024, an adult dairy farm worker had onset of redness and discomfort in the right eye. On presentation that day, subconjunctival hemorrhage and thin, serous drainage were noted in the right eye. Vital signs were unremarkable, with normal respiratory effort and an oxygen saturation of 97% while the patient was breathing ambient air. Auscultation revealed clear lungs. There was no history of fever or feverishness, respiratory symptoms, changes in vision, or other symptoms. The worker reported no contact with sick or dead wild birds, poultry, or other animals but reported direct and close exposure to dairy cows that appeared to be well and with sick cows that showed the same signs of illness as cows at other dairy farms in the same area of northern Texas with confirmed HPAI A(H5N1) virus infection (e.g., decreased milk production, reduced appetite, lethargy, fever, and dehydration). The worker reported wearing gloves when working with cows but did not use any respiratory or eye protection. Conjunctival and nasopharyngeal swab specimens were obtained from the right eye for influenza testing. The results of real-time reverse-transcription–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) testing were presumptive for influenza A and A(H5) virus in both specimens. On the basis of a presumptive A(H5) result, home isolation was recommended, and oral oseltamivir (75 mg twice daily for 5 days) was provided for treatment of the worker and for postexposure prophylaxis for the worker’s household contacts (at the same dose). The next day, the worker reported no symptoms except discomfort in both eyes; reevaluation revealed subconjunctival hemorrhage in both eyes, with no visual impairment. Over the subsequent days, the worker reported resolution of conjunctivitis without respiratory symptoms, and household contacts remained well.... Published in NEJM (May 3, 2024):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The USDA tested 30 samples from states with herds infected by H5N1. Tests of ground beef purchased at retail stores have been negative for bird flu so far, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced Wednesday, after studying meat samples collected from states with herds infected by this year's unprecedented outbreak of the virus in cattle. The results "reaffirm that the meat supply is safe," the department said in a statement published late Wednesday after the testing was completed. Health authorities have cited the "rigorous meat inspection process" overseen by the department's Food Safety Inspection Service, or FSIS, when questioned about whether this year's outbreak in dairy cattle might also threaten meat eaters. "FSIS inspects each animal before slaughter, and all cattle carcasses must pass inspection after slaughter and be determined to be fit to enter the human food supply," the department said. The National Veterinary Services Laboratories tested 30 samples of ground beef in total, which were purchased at retail outlets in states with dairy cattle herds that had tested positive. To date, dairy cattle in at least nine states — Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Michigan, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota and Texas — have tested positive for H5N1, which is often lethal to poultry and other animals, like cats, but has largely spared cattle aside from sometimes disrupting their production of milk for a few weeks. A USDA spokesperson said the ground beef they tested came from stores in only eight of those states. Colorado was only confirmed to have H5N1 in a dairy cow after USDA had collected the samples. The spokesperson did not comment on whether beef from stores in additional states would be sampled. More results from the department related to bird flu in beef are expected soon. Samples collected from the beef muscle of dairy cows condemned by inspectors at slaughter facilities are still being tested for the virus. The department is also testing how cooking beef patties to different temperatures will kill off the virus. "I want to emphasize, we are pretty sure that the meat supply is safe. We're doing this just to enhance our scientific knowledge, to make sure that we have additional data points to make that statement," Dr. Jose Emilio Esteban, USDA under secretary for food safety, told reporters Wednesday. The studies come after the USDA ramped up testing requirements on dairy cattle moving across state lines last month in response to the outbreak. Officials said that was in part because it had detected a mutated version of H5N1 in the lung tissue of an asymptomatic cow that had been sent to slaughter. While the cow was blocked from entering the food supply by FSIS, officials suggested the "isolated" incident raised questions about how the virus was spreading. Signs of bird flu have also made its way into the retail dairy supply, with as many as one in five samples of milk coming back positive in a nationwide Food and Drug Administration survey. The FDA has chalked those up to harmless fragments of the virus left over after pasteurization, pointing to experiments showing that there was no live infectious virus in the samples of products like milk and sour cream that had initially tested positive. But the discovery has worried health authorities and experts that cows could be flying under the radar without symptoms, given farms are supposed to be throwing away milk from sick cows. One herd that tested positive in North Carolina remains asymptomatic and is still actively producing milk, a spokesperson for the state's Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services told CBS News. It remains unclear how H5N1 has ended up in the milk supply. Don Prater, the FDA's top food safety official, said Wednesday that milk processors "can receive milk from hundreds of different farms, which may cross state lines," complicating efforts to trace back the virus. "This would take extensive testing to trace it that far," Bailee Woolstenhulme, a spokesperson for the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food, told CBS News. Woolstenhulme said health authorities are only able to easily trace back milk to so-called "bulk tanks" that bottlers get. "These bulk tanks include milk from multiple dairies, so we would have to test cows from all of the dairies whose milk was in the bulk tank," Woolstenhulme said.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Virus has already killed other mammals including sea lions and seals, while also taking toll on farm animals. The first case of a walrus dying from bird flu has been detected on one of Norway’s Arctic islands, a researcher has said. The walrus was found last year on Hopen island in the Svalbard archipelago, Christian Lydersen, of the Norwegian Polar Institute, told AFP. Tests carried out by a German laboratory revealed the presence of bird flu, Lydersen said. The sample was too small to determine whether it was the H5N1 or the H5N8 strain. “It is the first time that bird flu has been recorded in a walrus,” Lydersen said. About six dead walrus were found last year in the Svalbard islands, about 1,000km (620 miles) from the north pole and halfway between mainland Norway and the north pole.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

In early March, veterinarian Barb Petersen noticed the dairy cows she cared for on a Texas farm looked sick and produced less milk, and that it was off-color and thick. Birds and cats on the farm were dying, too. Petersen contacted Kay Russo at Novonesis, a company that helps farms keep their animals healthy and productive. “I said, you know, I may sound like a crazy, tinfoil hat–wearing person,” Russo, also a veterinarian, recalled at a 5 April public talk sponsored by her company. “But this sounds a bit like influenza to me.” She was right, as Petersen and Russo soon learned. On 19 March, birds on the Texas farm tested positive for H5N1, the highly pathogenic avian flu that has been devastating poultry and wild birds around the world for more than 2 years. Two days later, tests of cow milk and cats came back positive for the same virus, designated 2.3.4.4b. “I was at Target with my kids, and a series of expletives came out of my mouth,” Russo said. Now, 3 weeks into the first ever outbreak of a bird flu virus in dairy cattle, Russo and others are still dismayed—this time by the many questions that remain about the infections and the threat they may pose to livestock and people, and by the federal response. Eight U.S. states have reported infected cows, but government scientists have released few details about how the virus is spreading. In the face of mounting criticism about sharing little genetic data—which could indicate how the virus is changing and its potential for further spread—the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) did an unusual Sunday evening dump on 21 April of 202 sequences from cattle into a public database. (Some may be different samples from the same animal.) And despite public reassurances about the safety of the country’s milk supply, officials have yet to provide supporting data. The cow infections, first confirmed by USDA on 25 March, were “a bit of an inconvenient truth,” Russo says. Taking and testing samples, sequencing viruses, and running experiments can take days, if not weeks, she acknowledges. But she thinks that although officials are trying to protect the public, they are also hesitant to cause undue harm to the dairy and beef industries. “There is a fine line of respecting the market, but also allowing for the work to be done from a scientific perspective,” Russo says. Only one human case linked to cattle has been confirmed to date, and symptoms were limited to conjunctivitis, also known as pink eye. But Russo and many other vets have heard anecdotes about workers who have pink eye and other symptoms—including fever, cough, and lethargy—and do not want to be tested or seen by doctors. James Lowe, a researcher who specializes in pig influenza viruses, says policies for monitoring exposed people vary greatly between states. “I believe there are probably lots of human cases,” he says, noting that most likely are asymptomatic. Russo says she is heartened that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has “really started to mobilize and do the right thing,” including linking with state and local health departments, as well as vets, to monitor the health of workers on affected farms. As farms in more states began to report infected dairy cows last month, one theory held migratory birds were carrying the virus across the country and introducing it repeatedly to different dairy herds. But Lowe dismisses the idea as “some fanciful thinking by some cow veterinarians and some cow producers” who hoped to “protect the industry.” Richard Webby, an avian influenza researcher at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, notes that available data on the virus’ genetic sequence show “no smoking guns”—mutations that could enable it to jump readily from birds to cows. At a 4 April meeting organized by a group known as the Global Framework for the Progressive Control of Transboundary Animal Diseases, Suelee Robbe Austerman of USDA’s National Veterinary Services Laboratory said “a single spillover event or a couple of very closely related spillover events” from birds is more likely. The cow virus—which USDA has designated 3.13—could then have moved between farms as southern herds were moved northward for the spring, perhaps spreading from animal to animal on milking equipment. Lowe notes that researchers at Iowa State necropsied infected cows and found no virus in their respiratory tracts, which could enable spread through the air. USDA considers H5N1 in poultry a “program disease,” which means it is foreign to the country and subject to regulations to control it. But the agency has made no such determination for the cow disease, which means the federal government has no power to restrict movement of cattle or to require testing and reporting of infected herds or of the humans who work with them. As a result, confusion is rife. A knowledgeable source who asked not to be identified says cattle that were healthy when they left a Texas farm appear to have brought the virus to a North Carolina farm. That raises the possibility that many cattle are infected but asymptomatic, which would make the virus harder to contain. Evidence suggests it has spread from cattle back to poultry, USDA says. Another source told Sciencenone that birds tested positive for the 3.13 strain and were culled at a Minnesota turkey farm right next to a dairy farm that refused to test its cattle. The industry and veterinarians bear some responsibility for the confusion, Lowe says. “We didn’t even try to get ahead of this thing,” he says. “That’s a black mark on the industry and on the profession.” Webby also faults USDA for not releasing data more quickly. The agency made six sequences from cattle—plus six related ones from birds and one from a skunk—available on the GISAID database on 29 March, 1 week after learning that cows were infected. It released one more sequence on 5 April, but then shared nothing else until the data dump 16 days later. Webby suspects the agency has moved cautiously because of the potential impact on the dairy industry. “There are a lot of people who are vested in this, and their livelihoods, at least on paper, can be impacted by whatever is found.” Thijs Kuiken, an avian influenza researcher at Erasmus Medical Center, says the “very sparse” information released by the U.S. government has international implications, too. State and federal animal health authorities have “abundant information … that [has] not been made public, but would be informative for health professionals and scientists” in the United States and abroad, he says, “to be able to better assess the outbreak and take measures, both for animal health and for human health.” He notes that even the new sequences released by USDA do not include locations of the samples or the date they were taken. USDA said in a statement to Sciencenone that it will continue “to provide timely and accurate updates” and that its staff “are working around the clock” on a thorough epidemiological investigation to determine routes of transmission and help control spread. With its Sunday evening release, USDA made the unusual move to bypass GISAID—which requires a login and restricts how data can be used—and instead posted on a database run by the National Institutes of Health that everyone can access and do with as they please. USDA explained it did this “in the interest of public transparency and ensuring the scientific community has access to this information as quickly as possible to encourage disease research.” The dairy industry is particularly worried that sales could suffer because of unwarranted fears that milk might infect people with the virus. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has said it has “no concern” that pasteurized milk presents risks because the process “has continually proven to inactivate bacteria and viruses, like influenza, in milk.” But Lowe says for this specific virus, there are no data to back that claim. That’s “shocking,” he says. “It should not be that hard to get that data. I do not know why the foot dragging is occurring there.” In a statement to Sciencenone, FDA said the agency is working to “reinforce our current assessment that the commercial milk supply is safe” and will share data as soon as possible. “U.S. government partners are working with all deliberate speed on a wide range of studies looking at milk along all stages of production, including on the farm, during processing and on shelves,” the statement said. Daniel Perez, an influenza researcher at the University of Georgia, is doing his own test tube study of pasteurization of milk spiked with a different avian influenza virus. The fragile lipid envelope surrounding influenza viruses should make them vulnerable, he says. Still, he wonders whether the commonly used “high temperature, short time” pasteurization, which heats milk to about 72°C for 15 or 20 seconds, is enough to inactivate all the virus in a sample. Lowe predicts that with increased safety precautions at farms, including more rigorous cleaning of milking equipment, and the end to the seasonal movement of cattle, this outbreak likely will die out—as often happens when bird influenza viruses infect mammals that do not make particularly good hosts. But he and other researchers say to truly assess the continuing threat of H5N1 in cattle, they need to understand how this virus succeeded at infecting dairy cows in the first place. “Which cells is the virus replicating in? How is it getting around the body? What receptor is it using to get into cells?” Lowe wonders. “Those are the really interesting questions.” Correction, 23 April 2024, 7:35 a.m.: A previous version of this story said James Lowe necropsied infected cows. He didn't but noted that researchers at Iowa State University did.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

As the virus continues its spread to new species, the World Health Organization fears it is moving closer to people. The risk of bird flu jumping into humans is of “enormous concern,” the World Health Organization has warned as the virus continues its spread into new species. Since 2020, an outbreak of the H5N1 strain has killed tens of millions of birds worldwide, along with thousands of mammals, including sea lions, elephant seals and even one polar bear. More recently, the virus emerged in 16 herds of cattle in Texas – a development which has surprised experts, as it was previously believed the animals were not susceptible to infection, and raised concerns that H5N1 could eventually spill over into humans. “This remains, I think, an enormous concern,” Dr Jeremy Farrar, the WHO’s chief scientist, told reporters on Thursday in Geneva. “When you come into the mammalian population, then you’re getting closer to humans … this virus is just looking for new, novel hosts.” He warned that, by circulating in new mammals, the virus improves its chances of further evolving and developing “the ability to infect humans and then critically the ability to go from human to human”. In the recent cattle outbreak in Texas, one person was diagnosed with bird flu following close contact with dairy cows presumed to have been infected. Over the past 20 years, hundreds of others have caught the virus following exposure to an infected animal – yet there has been no evidence of human-to-human transmission in these cases. Yet the mortality rate for humans is “extraordinarily high,” Dr Farrar warned. From 2003 to 2024, 463 deaths and 889 cases were reported from 23 countries, according to the WHO – a case fatality rate of 52 per cent. The Texas infection is the second case of bird flu in the US and appears to have been the first infection of the H5N1 strain through contact with an infected mammal, said the WHO. Dr Farrar said the ongoing bird flu outbreak had become “a global zoonotic animal pandemic” and called for increased monitoring, adding that it was “very important” to understand how many human infections are occuring “because that’s where adaptation [of the virus] will happen”. He added: “It’s a tragic thing to say, but if I get infected with H5N1 and I die, that’s the end of it. If I go around the community and I spread it to somebody else then you start the cycle.” He said efforts were being made to develop vaccines and therapeutics for the strain and stressed the importance of international health authorities having the capacity to diagnose the virus. This would ensure that the world would be “in a position to immediately respond” if the strain “did come across to humans, with human-to-human transmission”, said Dr Farrar.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

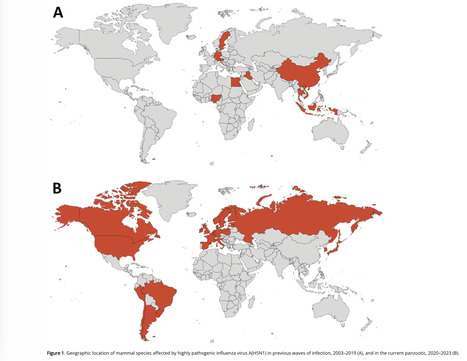

We reviewed information about mammals naturally infected by highly pathogenic avian influenza A virus subtype H5N1 during 2 periods: the current panzootic (2020–2023) and previous waves of infection (2003–2019). In the current panzootic, 26 countries have reported >48 mammal species infected by H5N1 virus; in some cases, the virus has affected thousands of individual animals. The geographic area and the number of species affected by the current event are considerably larger than in previous waves of infection. The most plausible source of mammal infection in both periods appears to be close contact with infected birds, including their ingestion. Some studies, especially in the current panzootic, suggest that mammal-to-mammal transmission might be responsible for some infections; some mutations found could help this avian pathogen replicate in mammals. H5N1 virus may be changing and adapting to infect mammals. Continuous surveillance is essential to mitigate the risk for a global pandemic. Since last century, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses have caused diverse waves of infection. However, the ongoing panzootic event (2020–2023) caused by HPAI A(H5N1) virus could become one of the most important in terms of economic losses, geographic areas affected, and numbers of species and individual animals infected. This pathogen appears to be emerging in several regions of the world (e.g., South America); it has caused death in domestic and wild birds but also in mammals. This trend is of great concern because it may indicate a change in the dynamics of this pathogen (i.e., an increase in their range of hosts and the severity of the disease). H5N1 has affected several mammal species since 2003, thus raising concern because H5N1 mammalian adaptation could represent a risk not only for diverse wild mammals but also for human health. Unfortunately, information about this topic, especially related to the current panzootic (2020–2023), is disperse and available often only in gray literature (e.g., databases and official government websites). This fact complicates access and evaluation for many stakeholders working on the front lines (e.g., wildlife managers, conservationists, and public health authorities at regional and local levels). For this article, we compiled and analyzed information from scientific literature about mammal species, including humans, naturally affected by the current panzootic event and compared those findings with the outcomes of previous waves of H5N1 infection. We focus particularly on the species infected, their habitat, phylogeny, and trophic level, and the sources of infection, virus mutations, clinical signs, and necropsy findings associated with this virus. We also address potential risks for biodiversity and human health. Published in Emerging Infectious Diseases (March 2024): https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3003.231098

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Health Alert Network (HAN). Provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Summary The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is issuing this Health Alert Network (HAN) Health Advisory to inform clinicians, state health departments, and the public of a recently confirmed human infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) virus in the United States following exposure to presumably infected dairy cattle. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) recently reported detections of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in U.S. dairy cattle in multiple states. This Health Advisory also includes a summary of interim CDC recommendations for preventing, monitoring, and conducting public health investigations of potential human infections with HPAI A(H5N1) virus. Background

A farm worker on a commercial dairy farm in Texas developed conjunctivitis on approximately March 27, 2024, and subsequently tested positive for HPAI A(H5N1) virus infection. HPAI A(H5N1) viruses have been reported in the area’s dairy cattle and wild birds. There have been no previous reports of the spread of HPAI viruses from cows to humans. The patient reported conjunctivitis with no other symptoms, was not hospitalized, and is recovering. The patient was recommended to isolate and received antiviral treatment with oseltamivir. Illness has not been identified in the patient’s household members, who received oseltamivir for post-exposure prophylaxis per CDC Recommendations for Influenza Antiviral Treatment and Chemoprophylaxis. No additional cases of human infection with HPAI A(H5N1) virus associated with the current infections in dairy cattle and birds in the United States, and no human-to-human transmission of HPAI A(H5N1) virus have been identified.

CDC has sequenced the influenza virus genome identified in a specimen collected from the patient and compared it with HPAI A(H5N1) sequences from cattle, wild birds, and poultry. While minor changes were identified in the virus sequence from the patient specimen compared to the viral sequences from cattle, both cattle and human sequences lack changes that would make them better adapted to infect mammals. In addition, there were no markers known to be associated with influenza antiviral drug resistance found in the virus sequences from the patient’s specimen, and the virus is closely related to two existing HPAI A(H5N1) candidate vaccine viruses that are already available to manufacturers, and which could be used to make vaccine if needed. This patient is the second person to test positive for HPAI A(H5N1) virus in the United States. The first case was reported in April 2022 in Colorado in a person who had contact with poultry that was presumed to be infected with HPAI A(H5N1) virus. Currently, HPAI A(H5N1) viruses are circulating among wild birds in the United States, with associated outbreaks among poultry and backyard flocks and sporadic infections in mammals....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

This is a technical summary of an analysis of the genomic sequences of viruses associated with an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) viruses in Texas. This analysis supports the conclusion that the overall risk to the general public associated with the ongoing HPAI A(H5N1) outbreak has not changed and remains low at this time. The genome of the virus identified from the patient in Texas is publicly posted in GISAID and has been submitted to GenBank. April 2, 2024 – CDC has sequenced the influenza virus genome identified in a specimen collected from the patient in Texas who was confirmed to be infected with highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) [“HPAI A(H5N1)”] virus and compared these with HPAI A(H5N1) sequences from cattle, wild birds and poultry. The virus sequences are HA clade 2.3.4.4b HPAI A(H5N1) with each individual gene segment closely related to viruses detected in dairy cattle available from USDA testing in Texas. While minor changes were identified in the virus sequence from the patient specimen compared to the viral sequences from cattle, both cattle and human sequences maintain primarily avian genetic characteristics and for the most part lack changes that would make them better adapted to infect mammals. The genome for the human isolate had one change (PB2 E627K) that is known to be associated with viral adaptation to mammalian hosts, and which has been detected before in people and other mammals infected with HPAI A(H5N1) virus and other avian influenza subtypes (e.g., H7N9), but with no evidence of onward spread among people. Viruses can undergo changes in a host as they replicate after infection. Further, there are no markers known to be associated with influenza antiviral resistance found in the virus sequences from the patient’s specimen and the virus is very closely related to two existing HPAI A(H5N1) candidate vaccine viruses that are already available to manufacturers, and which could be used to make vaccine if needed. Overall, the genetic analysis of HPAI A(H5N1) viruses in Texas supports CDC’s conclusion that the human health risk currently remains low. More details are available in this technical summary below...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

U.S. regulators confirmed that sick cattle in Texas, Kansas and possibly in New Mexico contracted avian influenza. They stressed that the nation’s milk supply is safe. A highly fatal form of avian influenza, or bird flu, has been confirmed in U.S. cattle in Texas and Kansas, the Department of Agriculture announced on Monday. It is the first time that cows infected with the virus have been identified. The cows appear to have been infected by wild birds, and dead birds were reported on some farms, the agency said. The results were announced after multiple federal and state agencies began investigating reports of sick cows in Texas, Kansas and New Mexico. In several cases, the virus was detected in unpasteurized samples of milk collected from sick cows. Pasteurization should inactivate the flu virus, experts said, and officials stressed that the milk supply was safe. “At this stage, there is no concern about the safety of the commercial milk supply or that this circumstance poses a risk to consumer health,” the agency said in a statement. Outside experts agreed. “It has only been found in milk that is grossly abnormal,” said Dr. Jim Lowe, a veterinarian and influenza researcher at the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In those cases, the milk was described as thick and syrupy, he said, and was discarded. The agency said that dairies are required to divert or destroy milk from sick animals.... USDA report (March 25, 2024): https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/news/sa_by_date/sa-2024/hpai-cattle

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Tissue samples from a polar bear that was found dead have tested positive for the virus. A highly lethal form of bird flu that has been spreading across the world has now been detected in a dead polar bear in Alaska. It is the first known case in the Arctic animals, which are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Why It Matters: The virus is a new threat for many wild mammals. The infected polar bear provides further evidence of how widespread this virus, a highly pathogenic form of H5N1, has become and how unprecedented its behavior has been. Since the virus emerged in 2020, it has spread to every continent except for Australia. It has also infected an unusually broad array of wild birds and mammals, including foxes, skunks, mountain lions and sea lions. “The number of mammals reported with infections continues to grow,” Dr. Bob Gerlach, Alaska’s state veterinarian, said. In most cases, the virus has not caused mass die-offs in wild mammal populations. (South American sea lions have been one notable exception.) But it does represent a new threat for the already vulnerable polar bear, which is imperiled by climate change and the loss of sea ice. “The concern is that we don’t know the overall extent of what the virus may do in the polar bear species,” Dr. Gerlach said. Background: The bear showed signs of disease. The polar bear was found dead this past fall in far northern Alaska, near Utqiagvik. Swabs collected from the animal initially tested negative for the virus. But when experts conducted a more comprehensive work-up, performing a necropsy and collecting tissue samples from the bear, they found clear signs of inflammation and disease, Dr. Gerlach said. Last month, tissue samples from the bear tested positive for the virus, according to the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation. The virus was ultimately identified in multiple organs, Dr. Gerlach said. “I think it would be a safe thing to say that it died from the virus,” he said. Alaska has previously reported infections in a brown bear and a black bear, as well as in several red foxes. What We Don’t Know: Have other polar bears been infected? It is not clear how the polar bear contracted the virus, but sick birds had been reported in the area. The polar bear might have been infected after eating a dead or ailing bird, Dr. Gerlach said. And scientists don’t know whether this case is a one-off or whether there are other infected polar bears that have escaped detection. It can be tricky to monitor the virus in wild animal populations, especially those that live in places as remote as northern Alaska. “How do you know how many are affected?” Dr. Gerlach said. “We really don’t.” Local scientists, officials and other experts will continue to look for signs of the virus in wild animals, including in polar bears that turn up dead or seem sick, Dr. Gerlach said. Emily Anthes is a science reporter, writing primarily about animal health and science. She also covered the coronavirus pandemic.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Mexican animal safety authorities confirmed the first case of H5N1 avian influenza in a wild bird on Wednesday, after declaring the country's poultry farms free of the virus earlier in the day. A case of H5N1 avian influenza was found in a "clinically healthy" migratory duck in the state of Jalisco, the animal safety agency Senasica, which is part of the agriculture ministry, said in a statement. Earlier, the government declared in its official gazette that the country was H5N1 free, almost a year after starting a bird vaccination campaign in high-risk areas to prevent its spread. Senasica stressed that the confirmed H5N1 case does not signal an outbreak of the disease or contradict that declaration but instead it means that poultry farmers should be on alert to prevent the entry of infected wild birds. The H5N1-free designation facilitates the sale of live poultry, as well as poultry products and by-products originating in Mexico, according to the gazette. Last October, the agriculture ministry reported it had detected the virus in a 60,000-bird commercial farm in the state of Nuevo Leon a few days after notifying the World Organization for Animal Health of a first case of the serious strain. To guarantee Mexico remains free of the disease, it will maintain epidemiological surveillance, traceability, control of movement and other strict safety procedures, the government said in the document. The Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, commonly called bird flu, has led to the culling of millions of birds in the United States and Europe. In May, Brazil decreed a 180-day animal health emergency after detecting several cases, and Ecuador confirmed the presence of the virus in some birds in the Galapagos Islands in September.

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Avian influenza (serotype H5N1) is a highly pathogenic virus that emerged in domestic waterfowl in 1996. Over the past decade, zoonotic transmission to mammals, including humans, has been reported. Although human to human transmission is rare, infection has been fatal in nearly half of patients who have contracted the virus in past outbreaks. The increasing presence of the virus in domesticated animals raises substantial concerns that viral adaptation to immunologically naive humans may result in the next flu pandemic. Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) to track viruses was historically used to track polio and has recently been implemented for SARS-CoV2 monitoring during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, using an agnostic, hybrid-capture sequencing approach, we report the detection of H5N1 in wastewater in nine Texas cities, with a total catchment area population in the millions, over a two-month period from March 4th to April 25th, 2024. Sequencing reads uniquely aligning to H5N1 covered all eight genome segments, with best alignments to clade 2.3.4.4b. Notably, 19 of 23 monitored sites had at least one detection event, and the H5N1 serotype became dominant over seasonal influenza over time. A variant analysis suggests avian or bovine origin but other potential sources, especially humans, could not be excluded. We report the value of wastewater sequencing to track avian influenza. Preprint in medRxiv ( May 10, 2024): https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.05.10.24307179v1.full.pdf

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

An outbreak of H5N1 highly pathogenic influenza A virus (HPIAV) has been detected in dairy cows in the United States. Influenza A virus (IAV) is a negative-sense, single-stranded, RNA virus that has not previously been associated with widespread infection in cattle. As such, cattle are an extremely under-studied domestic IAV host species. IAV receptors on host cells are sialic acids (SAs) that are bound to galactose in either an α2,3 or α2,6 linkage. Human IAVs preferentially bind SA-α2,6 (human receptor), whereas avian IAVs have a preference for α2,3 (avian receptor). The avian receptor can further be divided into two receptors: IAVs isolated from chickens generally bind more tightly to SA-α2,3-Gal-β1,4 (chicken receptor), whereas IAVs isolated from duck to SA-α2,3-Gal-β1,3 (duck receptor). We found all receptors were expressed, to a different degree, in the mammary gland, respiratory tract, and cerebrum of beef and/or dairy cattle. The duck and human IAV receptors were widely expressed in the bovine mammary gland, whereas the chicken receptor dominated the respiratory tract. In general, only a low expression of IAV receptors was observed in the neurons of the cerebrum. These results provide a mechanistic rationale for the high levels of H5N1 virus reported in infected bovine milk and show cattle have the potential to act as a mixing vessel for novel IAV generation. Preprint in bioRxiv (May 3, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.03.592326

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses cross species barriers and have the potential to cause pandemics. In North America, HPAI A(H5N1) viruses related to the goose/Guangdong 2.3.4.4b hemagglutinin phylogenetic clade have infected wild birds, poultry, and mammals. Our genomic analysis and epidemiological investigation showed that a reassortment event in wild bird populations preceded a single wild bird-to-cattle transmission episode. The movement of asymptomatic cattle has likely played a role in the spread of HPAI within the United States dairy herd. Some molecular markers in virus populations were detected at low frequency that may lead to changes in transmission efficiency and phenotype after evolution in dairy cattle. Continued transmission of H5N1 HPAI within dairy cattle increases the risk for infection and subsequent spread of the virus to human populations. Preprint in bioRxiv (May 01, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.01.591751

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

We report highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in dairy cattle and cats in Kansas and Texas, United States, which reflects the continued spread of clade 2.3.4.4b viruses that entered the country in late 2021. Infected cattle experienced nonspecific illness, reduced feed intake and rumination, and an abrupt drop in milk production, but fatal systemic influenza infection developed in domestic cats fed raw (unpasteurized) colostrum and milk from affected cows. Cow-to-cow transmission appears to have occurred because infections were observed in cattle on Michigan, Idaho, and Ohio farms where avian influenza virus–infected cows were transported. Although the US Food and Drug Administration has indicated the commercial milk supply remains safe, the detection of influenza virus in unpasteurized bovine milk is a concern because of potential cross-species transmission. Continued surveillance of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in domestic production animals is needed to prevent cross-species and mammal-to-mammal transmission. Published in Emerging Infectious Diseases (April 20, 2024) https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3007.240508

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Bird flu isn’t just lurking inside cows, new research shows. Florida scientists have reported the first known case of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza in a common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). Though the case dates back to 2022, it’s the latest indication that these flu strains can potentially infect a wide variety of mammals. The report was published Friday in the Nature journal Communications Biology. According to the paper, the flu-infected dolphin was first identified on March 29, 2022. Researchers with the University of Florida’s Marine Animal Rescue Program were notified of a dolphin that appeared to be in clear distress around the waters of Horseshoe Beach in North Florida. By the time they arrived, however, the dolphin had already died. It was subsequently packed in ice and taken to the university for an autopsy the following day. The post-mortem examination found signs of poor health and inflammation in the dolphin’s brain and meninges (the membrane layers that protect the brain and spinal cord). The dolphin tested negative for other common infectious causes of brain inflammation, which prompted the researchers to expand their search. They knew that wild birds can develop neuroinflammation from highly pathogenic strains of avian influenza, that several bird die-offs tied to the flu had occurred in the area recently, and that recent outbreaks had occurred among other populations of marine mammals elsewhere, so they decided to screen for it. Testing then revealed the presence of H5N1 within the dolphin’s lungs and brain. There have been sightings of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in other marine mammals lately, such as harbor seals and other species of dolphins. But this is the first reported case documented in a common bottlenose dolphin and the first report in any cetacean (dolphins and whales) within the waters of North America. Strains of bird flu are classified as highly pathogenic when they cause severe illness and deaths in wild birds, so it’s not necessarily a given that they will be as dangerous to other animals they infect. The current outbreaks of H5N1 bird flu in cows, for instance, have caused generally mild illness to date. But strains belonging to this particular lineage of H5N1 (2.3.4.4b) have been deadly to marine mammals. The strain in this case did not appear to develop known genetic changes that would make it easier to infect and transmit between mammals, the authors found. But flu viruses mutate very quickly, leaving open the possibility that some strains will adapt and pick up the right changes that can make them a much bigger threat to mammals both on land and in the sea. “Human health risk aside, the consequences of A(H5N1) viruses adapting for enhanced replication in and transmission between dolphins and other cetacea could be catastrophic for these populations,” the authors wrote. The researchers are continuing to investigate the case, hoping to pinpoint the origins of the dolphin’s infection and to better understand the potential for bird flu strains to successfully jump the species barrier to these marine mammals. Studiy cited published in Communications Biology (April 18, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06173-x

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

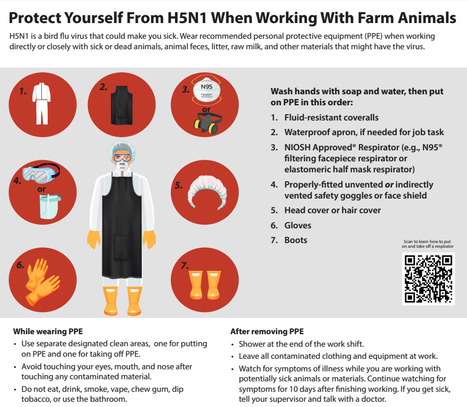

Recommendations for Worker Protection and Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to Reduce Exposure to Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A H5 Viruses - CDC Information for workers Any person working with or exposed to animals such as poultry and livestock farmers and workers, backyard bird flock owners, veterinarians and veterinary staff, and responders should take steps to reduce the risk of infection with avian influenza A viruses associated with severe disease when working with animals or materials potentially infected or confirmed to be infected with these viruses. Avoid unprotected direct or close physical contact with: - Sick birds, livestock, or other animals

- Carcasses of birds, livestock, or other animals

- Feces or litter

- Raw milk

- Surfaces and water (e.g., ponds, waterers, buckets, pans, troughs) that might be contaminated with animal excretions.

If you must work with or enter any not yet disinfected buildings where these materials or sick or dead animals potentially infected or confirmed to be infected are or were present, wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) in addition to the PPE you might be using for your normal duties (e.g., waterproof apron, hearing protection, etc.). Appropriate PPE depends on the hazards present and a site-specific risk assessment. If you have questions on the type of PPE to use or how to fit it properly, ask your supervisor. Recommended PPE to protect against novel influenza A viruses includes: - Disposable or non-disposable fluid-resistant [i] coveralls, and depending on task(s), add disposable or non-disposable waterproof apron

- Any NIOSH Approved® particulate respirator (e.g., N95® or greater filtering facepiece respirator, elastomeric half mask respirator with a minimum of N95 filters)

- Properly-fitted unvented or indirectly vented safety goggles [ii] or a faceshield if there is risk of liquid splashing onto the respirator

- Rubber boots or rubber boot covers with sealed seams that can be sanitized or disposable boot covers for tasks taking a short amount of time

- Disposable or non-disposable head cover or hair cover

- Disposable or non-disposable gloves [iii]

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The U.S. must act decisively, acknowledging the potential gravity of H5N1 mammalian transmission. Humans have no natural immunity to the bird flu virus. The recent detection of H5N1 bird flu in U.S. cattle, coupled with reports of a dairy worker contracting the virus, demands a departure from the usual reassurances offered by federal health officials. While they emphasize there’s no cause for alarm and assert diligent monitoring, it’s imperative we break from this familiar script. H5N1, a strain of the flu virus known to infect bird species globally and several mammalian species in the U.S. since 2022, has now appeared to have breached a new barrier of inter-mammalian transmission, as exemplified by the expanding outbreak in dairy cows in several jurisdictions linked to an initial outbreak in Texas. Over time, continued transmission among cattle is likely to yield mutations that will further increase the efficiency of mammal-to-mammal transmission. As the Centers for Disease Control continues to investigate, this evolutionary leap, if confirmed, underscores the adaptability of the H5N1 virus and raises concerns about the next step required for a pandemic: its potential to further evolve for efficient human transmission. Because humans have no natural immunity to H5N1, the virus can be particularly lethal to them. Despite assertions of an overall low risk of H5N1 infection to the general population, the reality is that the understanding of this risk is limited, and it’s evolving alongside the virus. The situation could change very quickly, so it is important to be prepared. Comparisons to seasonal flu management underestimate the unique challenges posed by H5N1. Unlike its seasonal counterparts, vaccines produced and stockpiled to tackle bird flu were not designed to match this particular strain and are available in such limited quantities that they could not make a dent in averting or mitigating a pandemic, even if deployed in the early stages to dairy workers. The FDA-approved H5N1 vaccines — licensed in 2013, 2017, and 2020 — do not elicit a protective immune response after just one dose. Even after two doses, it is unknown whether the elicited immune response is sufficient to protect against infection or severe disease, as these vaccines were licensed based on their ability to generate an immune response thought to be helpful in preventing the flu. Early studies done by mRNA vaccine companies on seasonal flu are promising, which could be good news here since mRNA vaccines can be made more quickly than vaccines using eggs or cells. Congressional funding is needed to catalyze rapid vaccine development and production. While FDA-approved antiviral drugs like Tamiflu and Xofluza could be an important line of defense against H5N1, logistical barriers impede their timely administration, as they work best when given as early as possible within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms. Most Americans would find it challenging to get a prescription filled for these medicines within the optimal time frame. Streamlining access to stockpiled antiviral drugs through improved test-to-treat measures like behind-the-counter distribution or dedicated telemedicine consultations could vastly improve their effectiveness as a frontline defense. Making plans to do that need to start now. For vulnerable people — older adults and anyone who is immunocompromised — clinicians have become accustomed to relying on monoclonal antibodies. Sadly, their performance for flu has been disappointing in many clinical trials and can’t be counted on. The need for robust diagnostic capabilities cannot be overstated. H5N1 will not be detected by the typical rapid flu antigen tests that are administered in emergency rooms and many doctors’ offices. New tests will have to be made from scratch. The dismantling of diagnostic infrastructure post-Covid-19 and supply chain disruptions, however, pose significant challenges to the availability of such tests. Rapid investment in diagnostic testing, coupled with efforts to secure essential materials, is imperative to ensure timely detection and antiviral treatment. President Biden’s emphasis on infrastructure presents a unique opportunity to fortify America’s defenses against infectious diseases. A national initiative to enhance indoor air quality in schools and communal spaces could mitigate transmission risks should this virus learn how to efficiently be transmitted between humans, and would pay dividends every respiratory virus season and for years to come. In the face of uncertainty, complacency is not an option. The U.S. must act decisively, acknowledging the potential gravity of the H5N1 situation while leveraging every available resource to safeguard public health. The stakes are too high to repeat past mistakes. Luciana Borio is an infectious disease physician, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations, a venture partner at ARCH Venture Partners, and former director for medical and biodefense preparedness policy at the National Security Council. Phil Krause is a virologist, infectious disease physician, and former deputy director of the Office of Vaccines Research and Review at the FDA. The authors have no links to any companies producing or evaluating any of the vaccines or therapies mentioned in this article, and declare no conflicts of interest.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A man in the Mekong Delta's Tien Giang Province has become the first person in Vietnam to be infected with avian flu A/H9. The 37-year-old man, who lives in Chau Thanh District, had a fever and purchased medicine to treat himself on March 10. As his conditions got serious, he was taken to the HCMC Hospital for Tropical Diseases on March 16, where doctors diagnosed him with severe viral pneumonia.A man in the Mekong Delta's Tien Giang Province tested positive with avian flu A/H9, becoming the first recorded case in Vietnam with the disease. Test results revealed that he had influenze A, and there were genetic segments similar to the A/H9 influenze strain. The Pasteur Institute of HCMC also confirmed the result. The man is under intensive care. The man lives near a wet market that sells poultry, and there is no sick or dead animal in the areas around the patient's family. Those who have had close contact with the patient have been listed and being monitored, and they have shown no signs of respiratory infection. No outbreaks have been recorded near the patient's neighborhood. The A/H9 influenza is an avian flu infectious to people. There have been no evidence to prove that the virus can be transmitted between humans. The Ministry of Health said the man from Tien Giang is the first recorded case of A/H9 in Vietnam. From 2015 to 2023, 98 such cases have been recorded within the West Pacific region, with two deaths. There is currently no cure or vaccine for avian flu. Death rates for avian flu may reach 50%, while the rates for normal flu is at 1-4%.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The bird flu virus spreading through dairy cattle in the United States may be expanding its reach via milking equipment, the people doing the milking, or both, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) representatives reported today at an international, virtual meeting held to update the situation. The avian virus may not be spreading directly from cows breathing on cows, as some researchers have speculated, according to USDA scientists who took part in the meeting, organized jointly by the World Organisation for Animal Health and the United Nations’s Food and Agricultural Organization. “We haven’t seen any true indication that the cows are actively shedding virus and exposing it directly to other animals,” said USDA’s Mark Lyons, who directs ruminant health for the agency and presented some of its data. The finding might also point to ways to protect humans. So far one worker at a dairy farm with infected cattle was found to have the virus, but no other human cases have been confirmed. USDA researchers tested milk, nasal swabs, and blood from cows at affected dairies and only found clear signals of the virus in the milk. “Right now, we don’t have evidence that the virus is actively replicating within the body of the cow other than the udder,” Suelee Robbe Austerman of USDA’s National Veterinary Services Laboratory told the gathering. The virus might be transmitted from cow to cow in milk droplets on dairy workers’ clothing or gloves, or in the suction cups attached to the udders for milking, Lyons said. (In a 30 March interview with Sciencenone, Thijs Kuiken, a leading avian influenza researcher at Erasmus Medical Center, had suggested the milking machines might be responsible because the components may not always be disinfected between cows.) The influenza virus causing the outbreak, an H5N1 subtype that is known as clade 2.3.4.4b, has devastated wild birds and poultry around the world for more than 2 years, and researchers at first thought migratory birds were responsible for spreading it to all of the affected dairy farms. But USDA scientists now think the movement of cattle, which are frequently transported from the southern parts of the country to the Midwest and north in the spring, may also have played an important role. And they floated the possibility, without naming specific herds or locations, that all affected cows may trace back to a single farm. Since first revealing the infection of dairy cows with this bird flu virus on 25 March, USDA has confirmed it has spread to cattle in six states. And the agency has used the virus’ genetics to track its movements. The virus found on U.S. farms has a specific genetic signature, which led USDA to name it 3.13. “It’s not a common [strain], but it’s very much a descendant of the viruses that have been dominating the flyways in the Pacific and the central flyways in the United States,” Robbe Austerman said. The USDA scientists reported that the agency’s analysis of the different viruses from the cows indicates they likely came from one source. Cows from infected farms in Texas appear to have moved the virus to farms in Idaho, Michigan, and Ohio. “The cow viruses so far have all been similar enough that it would be consistent with a single spillover event or a couple of very closely related spillover events,” Robbe Austerman said. “So far we don’t have any evidence that this is being introduced multiple times into the cows.” The virus in cows could spread to poultry, which has that industry on edge. USDA tightly regulates avian influenza virus strains that are deadly to poultry, requiring culling of entire flocks if one bird tests positive for this H5N1 or one of its relatives; to date, commercial and backyard poultry farms have had to cull 85 million birds because of this virus. But USDA is not calling for any such drastic measures with cow herds. In response to questions from Sciencenone, Ashley Peterson, who handles regulatory affairs for the National Chicken Council, said “out of an abundance of caution, we believe it is prudent to restrict the movement of cows from positive herds.” Although some researchers agree USDA should stop the transport of dairy cows, the agency has so far declined to take that disruptive action. “We heavily rely on the producers who have been isolating the animals within the dairy herds,” Lyons said. USDA also says it has no evidence of beef cattle becoming infected. USDA and the Food and Drug Administration have stressed that pasteurization kills viruses, so there is “no concern” about the safety of commercial milk. They do recommend people not consume raw milk or products made from it. Sources tell Science none some dairy farms that were later shown to be infected first noticed dead cats as early as mid-February. The animals, which often drink spilled milk on farms, “were the canary in the mine,” one said. The cows’ milk was also unusually thick. Those signs, coupled with the discovery of dead birds on the farms, led to the testing of cow milk for the bird flu virus and the 25 March USDA announcement. Oddly, the dead birds on infected farms were not waterfowl, the migratory birds that typically spread the avian flu viruses to poultry, but “peridomestic” species such as grackles, blackbirds, and pigeons. One farm had the virus detected in poultry before it was found in its cows, and although Robbe Austerman said she hesitated to call it the “ancestral strain,” she noted that “all of the detection so far in cattle are clustered around that.” Further studies should clarify how the virus wound up in cows, which sometimes become infected with flu viruses but have never before been shown to have one that causes high mortality in birds. One possibility is that birds infected cows by shedding their droppings in the cows’ feed or water. But bird flu viruses in the past have also spread for many kilometers in the wind, moving from one poultry farm to another. So the current H5N1 strain could have moved from waterfowl to poultry to cattle—or directly from poultry to cattle and then even to the peridomestic birds. “This could be a multifactorial presentation that we’re seeing,” Lyons said. “Lots of questions still to be answered.”

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The Idaho State Department of Agriculture announced that HPAI, known as highly pathogenic avian influenza, or bird flu, has been found in dairy cattle in Idaho. This now brings the number of affected states to four, adding more evidence the virus may be spreading cow to cow. The cows were recently brought into the Cassia County dairy from another state that had found HPAI in dairy cattle, according to the ISDA. The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) announced that an investigation into mysterious illnesses in dairy cows in three states—Kansas, New Mexico, and Texas—was due to HPAI and that wild birds are the source of the virus. Symptoms of HPAI in cattle include: - Drop in milk production

- Loss of appetite

- Changes in manure consistency

- Thickened or colostrum-like milk

- Low-grade fever

At this stage, there is no concern about the safety of the commercial milk supply or that this circumstance poses a risk to consumer health. The pasteurization process of heating milk to a high temperature ensures milk and dairy products can be consumed safely. The ISDA encourages all dairy producers to closely monitor their herd and contact their local veterinarian immediately if cattle appear to show symptoms. HPAI is a mandatory reportable disease, and any Idaho veterinarians who suspect cases of HPAI in livestock should immediately report it to ISDA at 208-332-8540 or complete the HPAI Livestock Screen at agri.idaho.gov/main/animals/hpai/. APHIS (USDA) update on the dairy cattle bird flu outbreaks (March 29, 2024): https://www.aphis.usda.gov/news/agency-announcements/usda-fda-cdc-share-update-hpai-detections-dairy-cattle

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The Minnesota Board of Animal Health (MBAH) today announced that highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) has been detected in a baby goat that lived on a farm where an outbreak had recently been detected in poultry. Today’s announcement marks the first US detection in livestock. Health officials, including the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), are investigating the transmission of the virus on the farm, which is located in Stevens County in west-central Minnesota. All species on the farm have been placed under quarantine. Poultry had already been quarantined following the February outbreak. "This finding is significant because, while the spring migration is definitely a higher risk transmission period for poultry, it highlights the possibility of the virus infecting other animals on farms with multiple species, " said Minnesota state veterinarian Brian Hoefs, DVM. " Thankfully, research to-date has shown mammals appear to be dead-end hosts, which means they’re unlikely to spread HPAI further...."

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A new study highlights both the promise and the limitations of gene editing, as a highly lethal form of avian influenza continues to spread around the world. Scientists have used the gene-editing technology known as CRISPR to create chickens that have some resistance to avian influenza, according to a new study that was published in the journal Nature Communications on Tuesday. The study suggests that genetic engineering could potentially be one tool for reducing the toll of bird flu, a group of viruses that pose grave dangers to both animals and humans. But the study also highlights the limitations and potential risks of the approach, scientists said. Some breakthrough infections still occurred, especially when gene-edited chickens were exposed to very high doses of the virus, the researchers found. And when the scientists edited just one chicken gene, the virus quickly adapted. The findings suggest that creating flu-resistant chickens will require editing multiple genes and that scientists will need to proceed carefully to avoid driving further evolution of the virus, the study’s authors said. The research is “proof of concept that we can move toward making chickens resistant to the virus,” Wendy Barclay, a virologist at Imperial College London and an author of the study, said at a news briefing. “But we’re not there yet.” Some scientists who were not involved in the research had a different takeaway. “It’s an excellent study,” said Dr. Carol Cardona, an expert on bird flu and avian health at the University of Minnesota. But to Dr. Cardona, the results illustrate how difficult it will be to engineer a chicken that can stay a step ahead of the flu, a virus known for its ability to evolve swiftly. “There’s no such thing as an easy button for influenza,” Dr. Cardona said. “It replicates quickly, and it adapts quickly.” What to Know About Avian Flu The spread of H5N1. A new variant of this strain of the avian flu has spread widely through bird populations in recent years. It has taken an unusually heavy toll on wild birds and repeatedly spilled over into mammals, including minks, foxes and bears. Here’s what to know about the virus: What is avian influenza? Better known as the bird flu, avian influenza is a group of flu viruses that is well adapted to birds. Some strains, like the version of H5N1 that is currently spreading, are frequently fatal to chickens and turkeys. It spreads via nasal secretions, saliva and fecal droppings, which experts say makes it difficult to contain. Should humans be worried about being infected? Although the danger to the public is currently low, people who are in close contact with sick birds can and have been infected. The virus is primarily a threat to birds, but infections in mammals increase the odds that the virus could mutate in ways that make it more of a risk to humans, experts say. How can we stop the spread? The U.S. Department of Agriculture has urged poultry growers to tighten their farms’ biosecurity measures, but experts say the virus is so contagious that there is little choice but to cull infected flocks. The Biden administration has been contemplating a mass vaccination campaign for poultry. Is it safe to eat poultry and eggs? The Agriculture Department has said that properly prepared and cooked poultry and eggs should not pose a risk to consumers. The chance of infected poultry entering the food chain is “extremely low,” according to the agency. Can I expect to pay more for poultry products? Egg prices soared when an outbreak ravaged the United States in 2014 and 2015. The current outbreak of the virus — paired with inflation and other factors — has contributed to an egg supply shortage and record-high prices in some parts of the country. Avian influenza refers to a group of flu viruses that are adapted to spread in birds. Over the last several years, a highly lethal version of a bird flu virus known as H5N1 has spread rapidly around the globe, killing countless farmed and wild birds. It has also repeatedly infected wild mammals and been detected in a small number of people. Although the virus remains adapted to birds, scientists worry that it could acquire mutations that help it spread more easily among humans, potentially setting off a pandemic. Many nations have tried to stamp out the virus by increasing biosecurity on farms, quarantining infected premises and culling infected flocks. But the virus has become so widespread in wild birds that it has proved impossible to contain, and some nations have begun vaccinating poultry, although that endeavor presents some logistic and economic challenges. If scientists could engineer resistance into chickens, farmers would not need to routinely vaccinate new batches of birds. Gene editing “promises a new way to make permanent changes in the disease resistance of an animal,” Mike McGrew, an embryologist at the University of Edinburgh’s Roslin Institute and an author of the new study, said at the briefing. “This can be passed down through all the gene-edited animals, to all the offspring.” CRISPR, the gene-editing technology used in the study, is a molecular toolthat allows scientists to make targeted edits in DNA, changing the genetic code at a precise point in the genome. In the new study, the researchers used this approach to tweak a chicken gene that codes for a protein known as ANP32A, which the flu virus hijacks to copy itself. The tweaks were designed to prevent the virus from binding to the protein — and therefore keep it from replicating inside chickens. The edits did not appear to have negative health consequences for the chickens, the researchers said. “We observed that they were healthy, and that the gene-edited hens also laid eggs normally,” said Dr. Alewo Idoko-Akoh, who conducted the research as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Edinburgh. The researchers then sprayed a dose of flu virus into the nasal cavities of 10 chickens that had not been genetically edited, to serve as the control. (The researchers used a mild version of the virus different from the one that has been causing major outbreaks in recent years.) All of the control chickens were infected with the virus, which they then transmitted to other control chickens they were housed with. When the researchers administered flu virus directly into the nasal cavities of 10 gene-edited chickens, just one of the birds became infected. It had low levels of the virus and did not pass the virus on to other gene-edited birds. “But having seen that, we felt that it would be the responsible thing to be more rigorous, to stress test this and ask, ‘Are these chickens truly resistant?’” Dr. Barclay said. “‘What if they were to somehow encounter a much, much higher dose?’” When the scientists gave the gene-edited chickens a flu dose that was 1,000 times higher, half of the birds became infected. The researchers found, however, that they generally shed lower levels of the virus than control chickens exposed to the same high dose. The researchers then studied samples of the virus from the gene-edited birds that had been infected. These samples had several notable mutations, which appeared to allow the virus to use the edited ANP32A protein to replicate, they found. Some of these mutations also helped the virus replicate better in human cells, although the researchers noted that those mutations in isolation would not be enough to create a virus that was well adapted to humans. Seeing those mutations is “not ideal,” said Richard Webby, who is a bird flu expert at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and was not involved in the research. “But when you get to the weeds of these particular changes, then it doesn’t concern me quite so much.” The mutated flu virus was also able to replicate even in the complete absence of the ANP32A protein by using two other proteins in the same family, the researchers found. When they created chicken cells that lacked all three of these proteins, the virus was not able to replicate. Those chicken cells were also resistant to the highly lethal version of H5N1 that has been spreading around the world the last several years. The researchers are now working to create chickens with edits in all three of the genes for the protein family. The big question, Dr. Webby said, was whether chickens with edits in all three genes would still develop normally and grow as fast as poultry producers needed. But the idea of gene editing chickens had enormous promise, he said. “Absolutely, we’re going to get to a point where we can manipulate the host genome to make them less susceptible to flu,” he said. “That’ll be a win for public health.”

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...