A T cell discovery, "hachimoji" DNA, a new species of human, and mounting fears of espionage rounded off the list this year.

Discovery of a new T cell

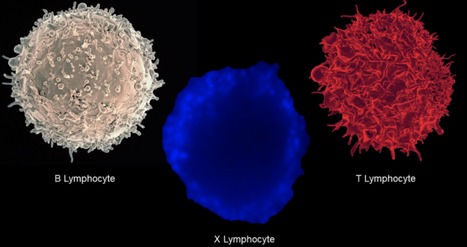

With all the extensive investigations scientists have conducted of the human immune system over the past century, it is astonishing that there are still new cell types to be found. Yet in May, researchers described a hybrid of B and T cells, which they named dual expresser (DE) cells, in people with type 1 diabetes. “We think [the DE cell peptide may play] a very major role during the initial phase of the disease,” Abdel Hamad, an immunologist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the senior author of the study, told The Scientist at the time. That same month, scientists also reported that humans’ natural killer cells, thought to form the innate immune response, can also keep memories of past encounters with offending antigens, much like the adaptive immune response does. The discovery challenges the basic dogma of how these cells function—another reminder there is still so much unknown even in our own blood.

Infectious diseases spread

Measles, Ebola, and polio flared up in 2019. Cases of measles in the US were the highest since the virus was declared eradicated in America in 2000, and they have been soaring in Europe and elsewhere. Public health officials say insufficient immunization, fueled by anti-vaccine sentiment, is to blame. All the while, scientists continued to learn about the virus—and just how dangerous it is. In October, researchers reported that infection with the virus that causes measles appears to leave the immune system vulnerable to infections by other pathogens.

Thousands of people died of measles this year in Democratic Republic of Congo, where an outbreak of Ebola has also been ongoing since the 2018. Violence in the region has hampered efforts to get the Ebola epidemic under control, but newly developed drugs and vaccines administered this year may help slow Ebola’s spread.

Polio will soon have another vaccine to contend with as researchers have developed one to designed to counteract the failure of an older vaccine that allowed the virus to continue to circulate and eventually revert to virulence. Such vaccine-derived polio cases have now become more common than those caused by the wild virus, but the new vaccine, which is genetically engineered to avoid such reversion, is set to be deployed in 2020....

First human-monkey chimeras

To “avoid legal issues,” researchers from Spain and the US developed the first human-monkey chimeras in China, a Spanish newspaper reported in July. The embryos’ development was stalled after a few weeks, but the scientists would like to grow animals whose organs could be harvested for human transplant, a goal at least one expert finds impractical. “I always made the case that it doesn’t make sense to use a primate for that. Typically they are very small, and they take too long to develop,” Pablo Ross, a veterinary researcher at the University of California, Davis, told MIT Technology Review.

While still illegal to pursue in the US using federal research funds, human-animal chimera projects got the regulatory green light in Japan last spring. “It’s good that they now allow people to do human-animal [chimera embryos] with species like pigs and sheep,” Sean Wu, a developmental biologist at Stanford University, told The Scientist in April. But human-primate chimeras are a different, um, animal. “There’s just too many things we don’t know about when you try to chimerize two species that are so close to each other, like humans with nonhuman primates.”....

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

https://recherchechimique.com/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-victoza-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-wegovy-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-saxenda-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-ozempic-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-mysimba-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/extase-molly/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/bleu-et-jaune-ikea-mdma-220mg/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-vyvanse-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/brun-donkey-kong-mdma-260mg/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-adderall-xr-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-du-cristal-de-mdma-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-du-marbre-hash-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-3-meo-pcp-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-acquista-xanax-2mg-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-de-lheroine-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-de-la-codeine-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-de-la-methadone-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-de-la-morphine-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-hydrocodone-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-oxycontin-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-percocet-en-ligne/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/ayahuasca-dmt/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/bonbons-au-lsd/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/buvards-lsd/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/comprimes-de-gel-de-lsd/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/cristaux-de-ketamine/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/deadhead-chimiste-dmt/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/glace-methamphetamine/

https://recherchechimique.com/produit/ketamine-hcl/

https://profarmaceutico.com/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-mounjaro-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-victoza-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-saxenda-6mg-ml-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ozempic-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-wegovy-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-mysimba-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-targin-40-mg-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-targin-20-mg-10-mg/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-targin-10-mg-5-mg-compresse/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-dysport-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-neuronox-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-bocouture-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-nembutal-in-polvere-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-online-nembutal-solution/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ketamina-hcl-500mg-10ml-in-linea/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-fentanyl-in-polvere-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-fentanyl-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-cristallo-mdma-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/a-215-ossicodone-actavis/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adderall-30mg/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adipex-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ossicodone-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-oxycontin-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-codeina-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adma-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ambien/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ativan-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-botox-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-cerotti-al-fentanil/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-codeina-linctus-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-demerol-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-depalgo-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-diazepam-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-idromorfone-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-endocet-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-eroina-bianca/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-hydrocodone-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-instanyl-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-l-ritalin-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-metadone/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-morfina-solfato/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-opana-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-percocet-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-phentermine-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-stilnox-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-suboxone-8mg/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-subutex-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-vicodin-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-vyvanse-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-xanax-2mg/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-rohypnol-2mg/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-sibutramina-online/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/efedrina-hcl-in-polvere/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/ephedrine-hcl-30mg/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/sciroppo-di-metadone/

https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/tramadolo-hcl-200mg/

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/a-215-ossicodone-actavis/">a-215-ossicodone-actavis</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adderall-30mg/">acquista-adderall-30mg</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adipex-online/">acquista-adipex-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ossicodone-online/">acquista-ossicodone-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-oxycontin-online/">acquista-oxycontin-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-codeina-online/">acquista-codeina-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adma-online/">acquista-adma-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ambien/">acquista-ambien</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ativan-online/">acquista-ativan-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-botox-online/">acquista-botox-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-cerotti-al-fentanil/">acquista-cerotti-al-fentanil</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-codeina-linctus-online/">acquista-codeina-linctus-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-demerol-online/">acquista-demerol-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-depalgo-online/">acquista-depalgo-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-diazepam-online/">acquista-diazepam-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-dilaudid-8mg/">acquista-dilaudid-8mg</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-endocet-online/">acquista-endocet-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-eroina-bianca/">acquista-eroina-bianca</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-green-xanax/">acquista-green-xanax</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-hydrocodone-online/">acquista-hydrocodone-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-instanyl-online/">acquista-instanyl-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-l-ritalin-online/">acquista-l-ritalin-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-metadone/">acquista-metadone</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-morfina-solfato/">acquista-morfina-solfato</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-opana-online/">acquista-opana-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-percocet-online/">acquista-percocet-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-phentermine-online/">acquista-phentermine-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-roxy-roxicodone-30-mg/">acquista-roxy-roxicodone-30-mg</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-stilnox-online/">acquista-stilnox-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-suboxone-8mg/">acquista-suboxone-8mg</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-subutex-online/">acquista-subutex-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-vicodin-online/">acquista-vicodin-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-vyvanse-online/">acquista-vyvanse-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-xanax-2mg/">acquista-xanax-2mg</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-dapoxetina-online/">acquistare-dapoxetina-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-rohypnol-2mg/">acquistare-rohypnol-2mg</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-sibutramina-online/">acquistare-sibutramina-online</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/efedrina-hcl-in-polvere/">efedrina-hcl-in-polvere</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/ephedrine-hcl-30mg/">ephedrine-hcl-30mg</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/sciroppo-di-metadone/">sciroppo-di-metadone</a>;

<a href="https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/tramadolo-hcl-200mg/">tramadolo-hcl-200mg</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/extase-molly/">extase-molly</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/bleu-et-jaune-ikea-mdma-220mg/">bleu-et-jaune-ikea-mdma-220mg</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-vyvanse-en-ligne/">cheter-vyvanse-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/5-meo-dmt-5ml-purecybine/">5-meo-dmt-5ml-purecybine</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/a-champignons-magiques/">a-champignons-magiques</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-du-marbre-hash-en-ligne/">acheter-du-marbre-hash-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-3-meo-pcp-en-ligne/">acheter-3-meo-pcp-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-acquista-xanax-2mg-en-ligne/">acheter-acquista-xanax-2mg-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-de-lheroine-en-ligne/">acheter-de-lheroine-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-adderall-xr-en-ligne/">acheter-adderall-xr-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-de-la-codeine-en-ligne/">acheter-de-la-codeine-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-de-la-methadone-en-ligne/">acheter-de-la-methadone-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-de-la-morphine-en-ligne/">acheter-de-la-morphine-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-des-champignons-magiques-alacabenzi-en-ligne/">acheter-des-champignons-magiques-alacabenzi-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-des-champignons-magiques-albino-a-en-ligne/">acheter-des-champignons-magiques-albino-a-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-des-champignons-magiques-albino-penis-envy-en-ligne/">acheter-des-champignons-magiques-albino-penis-envy-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-deschampignons-magiques-albinos-cambodgiens-en-ligne/">acheter-deschampignons-magiques-albinos-cambodgiens-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-du-cristal-de-mdma-en-ligne/">acheter-du-cristal-de-mdma-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-hydrocodone-en-ligne/">acheter-hydrocodone-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-oxycontin-en-ligne/">acheter-oxycontin-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/acheter-percocet-en-ligne/">acheter-percocet-en-ligne</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/ayahuasca-dmt/">ayahuasca-dmt</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/bonbons-au-lsd/">bonbons-au-lsd</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/brun-donkey-kong-mdma-260mg/">brun-donkey-kong-mdma-260mg</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/buvards-lsd/">buvards-lsd</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/champignons-magiques-albino-treasure-coast/">champignons-magiques-albino-treasure-coast</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/comprimes-de-gel-de-lsd/">comprimes-de-gel-de-lsd</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/cristaux-de-ketamine/">cristaux-de-ketamine</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/deadhead-chemist-dmt-3-cartouches-deal-5ml/">deadhead-chemist-dmt-3-cartouches-deal-5ml</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/deadhead-chimiste-5-meo-dmt-cartouche-5ml/">deadhead-chimiste-5-meo-dmt-cartouche-5ml</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/deadhead-chimiste-dmt/">deadhead-chimiste-dmt</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/glace-methamphetamine/">glace-methamphetamine</a>;

<a href="https://recherchechimique.com/produit/ketamine-hcl/">ketamine-hcl</a>;

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/a-215-ossicodone-actavis/" rel="dofollow">a-215-ossicodone-actavis</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adderall-30mg/" rel="dofollow">acquista-adderall-30mg</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adipex-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-adipex-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ossicodone-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-ossicodone-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-oxycontin-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-oxycontin-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-codeina-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-codeina-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adma-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-adma-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ambien/" rel="dofollow">acquista-ambien</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ativan-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-ativan-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-botox-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-botox-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-cerotti-al-fentanil/" rel="dofollow">acquista-cerotti-al-fentanil</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-codeina-linctus-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-codeina-linctus-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-demerol-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-demerol-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-depalgo-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-depalgo-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-diazepam-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-diazepam-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-dilaudid-8mg/" rel="dofollow">acquista-dilaudid-8mg</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-endocet-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-endocet-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-eroina-bianca/" rel="dofollow">acquista-eroina-bianca</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-green-xanax/" rel="dofollow">acquista-green-xanax</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-hydrocodone-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-hydrocodone-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-instanyl-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-instanyl-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-l-ritalin-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-l-ritalin-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-metadone/" rel="dofollow">acquista-metadone</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-morfina-solfato/" rel="dofollow">acquista-morfina-solfato</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-opana-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-opana-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-percocet-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-percocet-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-phentermine-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-phentermine-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-roxy-roxicodone-30-mg/" rel="dofollow">acquista-roxy-roxicodone-30-mg</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-stilnox-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-stilnox-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-suboxone-8mg/" rel="dofollow">acquista-suboxone-8mg</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-subutex-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-subutex-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-vicodin-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-vicodin-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-vyvanse-online/" rel="dofollow">acquista-vyvanse-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-xanax-2mg/" rel="dofollow">acquista-xanax-2mg</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-dapoxetina-online/" rel="dofollow">acquistare-dapoxetina-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-rohypnol-2mg/" rel="dofollow">acquistare-rohypnol-2mg</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-sibutramina-online/" rel="dofollow">acquistare-sibutramina-online</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/efedrina-hcl-in-polvere/" rel="dofollow">efedrina-hcl-in-polvere</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/ephedrine-hcl-30mg/" rel="dofollow">ephedrine-hcl-30mg</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/sciroppo-di-metadone/" rel="dofollow">sciroppo-di-metadone</a>

<a href="https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/tramadolo-hcl-200mg/" rel="dofollow">tramadolo-hcl-200mg</a>

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/a-215-ossicodone-actavis/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adderall-30mg/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adipex-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ossicodone-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-oxycontin-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-codeina-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-adma-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ambien/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-ativan-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-botox-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-cerotti-al-fentanil/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-codeina-linctus-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-demerol-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-diazepam-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-dilaudid-8mg/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-endocet-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-eroina-bianca/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-green-xanax/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-hydrocodone-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-instanyl-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-l-ritalin-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-metadone/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-morfina-solfato/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-opana-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-percocet-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-phentermine-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-roxy-roxicodone-30-mg/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-stilnox-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-suboxone-8mg/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-subutex-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-vicodin-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-vyvanse-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquista-xanax-2mg/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-dapoxetina-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-rohypnol-2mg/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/acquistare-sibutramina-online/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/efedrina-hcl-in-polvere/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/ephedrine-hcl-30mg/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/sciroppo-di-metadone/

https://www.google.it/url?q=https://profarmaceutico.com/Prodotto/tramadolo-hcl-200mg/