Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Explore the latest developments in Multiple Sclerosis research, focusing on the potential of a vaccine targeting the Epstein-Barr Virus. Learn about the impact of EBV on MS and the groundbreaking efforts towards vaccine development. Recent scientific advancements have brought hope in the fight against Multiple Sclerosis (MS), a debilitating neurological condition affecting millions worldwide. Key to this optimism is the potential development of a vaccine targeting the Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), a common factor in nearly all MS patients. Understanding Multiple Sclerosis and EBV Multiple Sclerosis is an autoimmune disease that leads to the destruction of myelin, the protective sheath surrounding nerve fibers. This results in a wide range of symptoms, including severe physical disability. The exact cause of MS remains unknown, but the link between MS and the Epstein-Barr Virus, known for causing mononucleosis, has been extensively documented. Research suggests that MS may develop when the immune system attacks myelin in the nervous system, confused by molecular similarities between myelin proteins and those produced by EBV. Groundbreaking Research and Vaccine Development A pivotal study tracking American military personnel revealed a significantly higher rate of EBV antibodies in those diagnosed with MS, reinforcing the virus's role in the disease's development. This discovery has led to the exploration of antiviral therapies aimed at reducing EBV in the immune system. Notably, Moderna and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases are at the forefront, developing vaccines focused on the gp350 protein of EBV. Though the journey to a comprehensive solution is ongoing, these efforts represent a significant leap towards potentially eradicating MS. The Road Ahead As the scientific community rallies behind these promising developments, the implications for MS treatment and prevention are profound. However, the effectiveness of these vaccines in preventing MS remains to be fully assessed, with years of research ahead. The potential for a world where MS can be prevented or substantially mitigated is on the horizon, thanks to these innovative strategies targeting the root causes of the disease. The battle against Multiple Sclerosis is entering a hopeful phase, with groundbreaking approaches offering a glimpse into a future where this devastating disease could be significantly controlled or even eliminated. While challenges remain, the dedication and innovation of researchers worldwide signal a potentially transformative era in MS treatment and prevention.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Scientists can now spot key differences in the blood of people who have long Covid symptoms— and those who don't. More than three years into the pandemic, the millions of people who have suffered from long Covid finally have scientific proof that their condition is real. Scientists have found clear differences in the blood of people with long Covid — a key first step in the development of a test to diagnose the illness. The findings, published Monday in the journal Nature, also offer clues into what could be causing the elusive condition that has perplexed doctors worldwide and left millions with ongoing fatigue, trouble with memory and other debilitating symptoms. The research is among the first to prove that "long Covid is, in fact, a biological illness," said David Putrino, principal investigator of the new study and a professor of rehabilitation and human performance at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Dr. Marc Sala, co-director of the Northwestern Medicine Comprehensive Covid-19 Center in Chicago, called the findings "important." He was not involved with the new research. "This will need to be investigated with more research, but at least it's something because, quite frankly, right now we don't have any blood tests" either to diagnose long Covid or help doctors understand why it's occurring, he said. Putrino and his colleagues compared blood samples of 268 people. Some had Covid but had fully recovered, some had never been infected, and the rest had ongoing symptoms of long Covid at least four months after their infection. Several differences in the blood of people with long Covid stood out from the other groups. The activity of immune system cells called T cells and B cells — which help fight off germs — was "irregular" in long Covid patients, Putrino said. One of the strongest findings, he said, was that long Covid patients tended to have significantly lower levels of a hormone called cortisol. A major function of the hormone is to make people feel alert and awake. Low cortisol could help explain why many people with long Covid experience profound fatigue, he said. "It was one of the findings that most definitively separated the folks with long Covid from the people without long Covid," Putrino said. The finding likely signals that the brain is having trouble regulating hormones. The research team plans to dig deeper into the role cortisol may play in long Covid in future studies. Meanwhile, doctors do not recommend simply boosting a person's cortisol levels in an attempt to "fix" the problem... Study published in Nature (Sept. 25, 2023): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06651-y

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

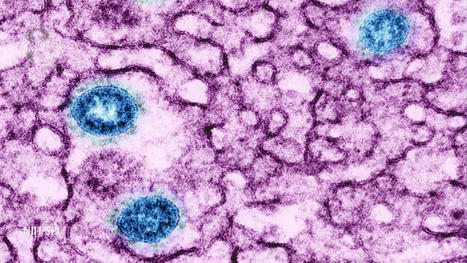

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is easily spread through bodily fluids, primarily saliva, such as kissing, shared drinks or using the same eating utensils. Not surprisingly then, EBV is also among the most ubiquitous of viruses: More than 90% of the world’s population has been infected, usually during childhood. EBV causes infectious mononucleosis and similar ailments, though often there are no symptoms. Most infections are mild and pass, but the virus persists in the body, becoming latent or inactive, sometimes reactivating. Long-term latent infections are associated with several chronic inflammatory conditions and multiple cancers. In a new paper, published April 12, 2023 in the journal Nature, researchers at University of California San Diego, UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center and Ludwig Cancer Research at UC San Diego, describe for the first time how the virus exploits genomic weaknesses to cause cancer while reducing the body’s ability to suppress it. These findings show “how a virus can induce cleavage of human chromosome 11, initiating a cascade of genomic instability that can potentially activate a leukemia-causing oncogene and inactivate a major tumor suppressor,” said senior study author Don Cleveland, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Medicine, Neurosciences and Cellular and Molecular Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “It’s the first demonstration of how cleavage of a ‘fragile DNA’ site can be selectively induced.” Throughout every person’s genome or full set of genes are fragile sites, specific chromosomal regions more likely to produce mutations, breaks or gaps when replicating. Some are rare, some are common; all are associated with disorders and disease, sometimes heritable conditions, sometimes not, such as many cancers. In the new study, Cleveland and colleagues focus on EBNA1, a viral protein that persists in cells infected with EBV. EBNA1 was previously known to bind at a specific genomic sequence in the EBV genome at the origin of replication. The researchers found that EBNA1 also binds a cluster of EBV-like sequences at a fragile site on human chromosome 11 where increasing abundance of the protein triggers chromosomal breakage. Other prior research has shown that EBNA1 inhibits p53, a gene that plays a key role in controlling cell division and cell death. It also suppresses tumor formation when normal. Mutations of p53, on the other hand, are linked to cancer cell growth. When the scientists examined whole-genome sequencing data for 2,439 cancers across 38 tumor types from the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes project, they found that cancer tumors with detectable EBV revealed higher levels of chromosome 11 abnormalities, including 100% of the head and neck cancer cases. “For a ubiquitous virus that is harmless for the majority of the human population, identifying at-risk individuals susceptible to the development of latent infection-associated diseases is still an ongoing effort,” said the study’s first author Julia Li, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Cleveland’s lab. “This discovery suggests that susceptibility to EBNA1-induced fragmentation of chromosome 11 depends on the control of EBNA1 levels produced in latent infection, as well as the genetic variability in the number of EBV-like sequences present on chromosome 11 in each individual. Going forward, this knowledge paves the way for screening risk factors for the development of EBV-associated diseases. Moreover, blocking EBNA1 from binding at this cluster of sequences on chromosome 11 can be exploited to prevent the development of EBV-associated diseases.” Published in Nature (April 12, 2023):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Led by the Department of Clinical Oncology, School of Clinical Medicine, LKS Faculty of Medicine, the University of Hong Kong (HKUMed), an international group of the world's top clinicians in managing nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) has recently published recommendations on measuring plasma EBV DNA in managing NPC in an acute setting of serious resource and personnel constraints during the COVID-19 pandemic. The international recommendations serve as important guidelines on future management of NPC when severe disasters or disruptions arise in future. The consensus statements of these recommendations were published in the oncology research journal The Lancet Oncology. NPC is endemic in Southern China, Southeast Asia, and North and East Africa, which is highly associated with prior Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. It is also common in Hong Kong, closely related to genetic predisposition and dietary factors such as consumption of Chinese-style salted fish, with an age-standardized incidence rate of 5.8 per 100,000 population in 2020, ranked 8th and 17th for males and females respectively. While histological proof is the gold standard in NPC diagnosis, plasma EBV DNA, the secretory DNA fragments of EBV, easily extracted in routine blood taking, has been regarded as the most sensitive and accurate tumor marker that has gained wide popularity and acceptance in NPC screening, diagnosis, stage segregation, treatment response monitoring, and prognostication. Currently, standard investigations in clinical management of NPC include clinical examinations, imaging scans and nasoendoscopy, a high-risk procedure of aerosol generation. However, the essential personnel, facilities and resources could be exceedingly scarce and constrained during the raging COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, it is sensible to consider whether plasma EBV DNA could replace nasoendoscopy, imaging scans, and even face-to-face clinical consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic and in the future when similar or even more devastating pandemics occur, leading to insufficiency of personnel and personal protective equipment. The Department of Clinical Oncology invited 33 top international clinicians from a broad range of clinical disciplines (head and neck surgery or otorhinolaryngology, medical oncology, radiation oncology and clinical oncology), representing 51 international professional societies and national clinical trial groups across four continents (Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America) during the COVID-19 pandemic to complete a modified Delphi consensus process of three rounds with 22 questions on whether plasma EBV DNA can replace the aforesaid routine clinical procedures and consultations in various clinical settings of NPC management when they are substantially restrained. In particular, all experts (100%) disagreed that the use of plasma EBV DNA and IgA viral capsid antigen, without imaging tools, could replace nasoendoscopy and biopsy as the only staging investigations for NPC in the resource-constrained setting. Even with the availability of imaging tools, 73% of the experts disagreed that the use of plasma EBV DNA should replace nasoendoscopy and biopsy as the only staging investigation for NPC. The findings revealed that although plasma EBV DNA (supplemented, when possible, by imaging scans) can be used in most clinical circumstances in the context of resource limitations, it cannot entirely replace nasoendoscopy and tumor biopsy. All experts who rejected the use of plasma EBV DNA as the only tool in NPC management maintained that these procedures are essential, and that the patients' right to receive these standard investigations should not be suppressed, insofar as the health-care system allows. These recommendations have taken into consideration various clinical scenarios from the joint perspectives of surgeons and non-surgeons, unlike previous recommendations published by individual clinical disciplines separately. Significance of the consensus In contrast to previous recommendations that endoscopic examinations should be exclusive to patients who are deemed to be at high risk of cancer recurrence and mortality from head and neck cancers and only when adequate personal protective equipment is available, this latest consensus concludes that merely measuring plasma EBV DNA should not replace the conventional but essential nasoendoscopic examinations, even when imaging services are very limited. Plasma EBV DNA combined with imaging scans can be considered an acceptable alternative in a very restricted clinical setting, but cannot replace face-to-face consultations and nasoendoscopy, and it cannot be used alone without imaging in NPC management. Dr. Victor Lee Ho-fun, chairperson and clinical associate professor, Department of Clinical Oncology, School of Clinical Medicine, HKUMed, who spearheaded and designed the survey, commented, "These recommendations, which are the results of concerted efforts of international collaboration and cooperation, can serve as references and be used in other acute settings or during natural disasters, where there is an unexpectedly high risk of health hazards to patients and health care workers and a severe paucity of health personnel and resources." Dr. Lee also hopes that "these recommendations can further stimulate international harmonization of plasma EBV DNA leading to more affordable use at institutions and hospitals in low-income and middle-income countries, and foster future researches in devising more sensitive and accurate tumor markers for NPC and other cancers when the pandemic is much contained." Published December 2022 in The Lancet Oncology: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00505-8

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

COVID-19 reactivated viruses that had become latent in cells following previous infections, particularly in people with chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as ME/CFS. This is the conclusion of a study from Linköping University in Sweden. The results, published in Frontiers in Immunology, contribute to our knowledge of the causes of the disease and prospects of reaching a diagnosis. Severe, long-term fatigue, post-exertional malaise, pain and sleep problems are characteristic signs of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, “ME/CFS”. The causes of the condition are not known with certainty, although it has been established that the onset in most cases follows a viral or bacterial infection. The health of the person affected is not restored even after the original infection is resolved. Indeed – the condition is sometimes known by its alternative name: post-viral fatigue. Since the cause is not known, diagnostic tests have not been developed. “This patient group has been neglected. Our study now shows that objective measurements are available that show physiological differences in the body’s reaction to viruses between ME patients and healthy controls,” says Anders Rosén, professor emeritus in the Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences (BKV) at Linköping University, and leader of the study. One theory that has been examined in several research studies is that a new infection can activate viruses that lie latent in the body’s cells after a previous infection. It has long been known that several herpes viruses, for example, can remain in a latent state in the body. Latent viruses can be reactivated many years later and give rise to a new bout of disease. It has, however, been difficult to determine whether such reactivated viruses are involved in ME/CFS – until now. The extensive spread of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus during the COVID-19 pandemic has given researchers a unique opportunity to study what happens in people with ME/CFS during a mild virus infection and compare this with what happens in healthy controls. In collaboration with the Bragée Clinic in Stockholm, the research group initiated a study early in the pandemic. Ninety-five patients who had been diagnosed with ME/CFS and 110 healthy controls participated in the study. They provided blood and saliva samples on four occasions during one year. The researchers analysed samples for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and latent viruses, and found a special fingerprint of antibodies against common herpes viruses in saliva. One of these viruses was the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which has infected nearly everybody. Most people experience a mild infection during childhood. People who are infected with EBV in the teenage years can develop glandular fever, commonly called mononucleosis, and also known as “kissing disease”. The virus then remains in a latent condition in the body. The EBV virus may proliferate in situations in which the immune system is impaired, causing fatigue, an autoimmune responses, and increased risk of lymphoma, if allowed to continue. Approximately half of the participants were infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the first wave of the pandemic and developed mild COVID-19 (58% of those with ME/CFS and 41% of the control group). In more than one third of cases, infection had been asymptomatic, so the person had not been aware of the infection. After the SARS-CoV-2 infection had passed, however, the researchers detected specific antibodies in the saliva that suggested that three latent viruses had been strongly reactivated, one of them being EBV. The reactivation was seen both in patients with ME/CFS and in the control group, but was significantly stronger in the ME/CFS group. Anders Rosén describes what happens as a domino effect: infection with a new virus, SARS-CoV-2, can activate other, latent, viruses in the body. The researchers suggest that this can, in turn, give rise to a chain reaction with an elevated immune response. This can have negative consequences, one of which is that the immune system attacks certain tissues, such as nerve tissue, in the body. Previous studies have also shown that the mitochondria, which produce energy in the cells, are affected, which suppresses the energy metabolism of people with ME/CFS. “Another important result from the study is that we see differences in antibodies against the reactivated viruses only in the saliva, not in the blood. This means that we should use saliva samples when investigating antibodies against latent viruses in the future,” says Anders Rosén. He points out that there is a great deal of overlap between the symptoms of ME/CFS and those of long COVID, which is experienced by around one third of patients who contract COVID-19. Exhaustion after light exercise, brain fog and unrefreshing sleep are common symptoms, while impaired lung capacity and abnormal senses of smell and taste are more specific for long COVID. The researchers believe that the results from the study can contribute to developing immunological tests to diagnose ME/CFS, and possibly also long COVID. “We now want to continue and carry out more detailed investigations into the immune response in ME/CFS, and in this way understand the differences between the antibody responses against latent viruses,” says Eirini Apostolou, principal research engineer, and lead author of the article. The study was financially supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society and Linköping University. Some of the authors have financial interests in the Bragée Clinic. Study cited published in Frontiers in Immunology (Oct. 20, 2022): https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.949787

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Low cortisol levels and herpes-virus reactivation are associated with prolonged COVID-19 symptoms, preliminary research suggests. Researchers looking for biological drivers and markers of long COVID have linked the syndrome to herpes viruses, as well as to reduced levels of a stress hormone1. The exploratory study drew both praise and criticism from scientists contacted by Nature. “A major weakness of this paper is the very small sample size,” says infectious-disease specialist Michael Sneller at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in Bethesda, Maryland. “I would take with a huge grain of salt all these findings unless they are confirmed in larger studies.” But Danny Altmann, an immunologist at Imperial College London who was not involved in the study, says such reports are exactly what the long-COVID research community needs. “We’re really desperate to work out which drugs to test” for long COVID, he says. “The more studies we have like this, the more it enables us to race off and plan appropriate randomized, controlled trials.” The study, posted on the preprint server medRxiv, has not yet been peer reviewed. The disease that lingers Long COVID consists of a constellation of sometimes debilitating symptoms that last for months or years after a SARS-CoV-2 infection. It is common — affecting anywhere from 5% to 50% of people who contract COVID-19 — but researchers have few clues to its causes. The latest study, led by immunobiologist Akiko Iwasaki at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, involved performing tests that generated thousands of data points for each of 215 participants in an attempt to reveal key immunological features that distinguish people with long COVID from healthy individuals. The study included 99 people with long COVID — those who reported persistent symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection — and 116 healthy participants who had either never had COVID-19 or had recovered after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Most strikingly, the study found that in the long-COVID group, levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that has a role in regulating inflammation, blood sugar levels and sleep cycles, were about 50% lower than in healthy participants. The authors also found hints that in people with long COVID, Epstein–Barr virus, which can cause mononucleosis, and varicella-zoster virus, which causes chickenpox and shingles, might recently have been ‘reactivated’. Both of these viruses are in the herpes family, persist indefinitely in the body after infection and can start to multiply again after a period of quiescence. People in the long-COVID group also had unusual levels of certain types of blood and immune cell, as well as dysfunctional immune cells, suggesting that their immune systems are working overtime. Iwasaki cautions that the results do not suggest that low cortisol levels or herpes viruses cause long COVID, but that their association with the syndrome warrants further study. The findings build on previous reports associating low cortisol levels and Epstein–Barr virus with long COVID, including a Cell paper2 published in March. With only 215 participants, the Iwasaki’s study is relatively small, and only a subset of the participants were included in some parts of the work. For example, in the analysis of cortisol levels, the researchers included all 99 people with long COVID, but only 40 of the 116 healthy people. “The small number of controls compared to the long-COVID group is problematic” because it makes the study less statistically robust, says Sneller, who is leading a separate study on the drivers of long COVID. Iwasaki says that samples were collected from the remaining healthy volunteers later and are being sent for analysis this week. Another limitation of the study is that Iwasaki’s team did not analyse participants’ samples for the presence of the Epstein–Barr and varicella-zoster viruses, instead measuring levels of antibodies against the viruses. Members of the long-COVID group had higher levels of these antibodies than did the healthy people, which suggests a more recent reactivation of the virus, Iwasaki says. However, the only way to determine definitively whether there is current reactivation is to test for viral DNA in the blood. Iwasaki’s team is now running such tests. Her group also plans to test participants’ cortisol levels throughout the day, because the stress hormone’s levels tend to fluctuate, and to examine how immune features vary at different time points after infection. “This is an exploratory, hypothesis-generating study, and clearly not the conclusion to what long COVID is, but it does begin to open doors,” says Iwasaki. Published in Nature (August 25, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-02296-5

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

For many people, Epstein-Barr virus causes mild initial infection, but it is also linked to cancers and multiple sclerosis. What do we do about it? Statistically speaking, the virus known as Epstein-Barr is inside you right now. It is inside 95 percent of us. It spreads through saliva, so perhaps you first caught the virus as a baby from your mother, who caught it as a baby from her mother. Or you picked it up at day care. Or perhaps from a friend with whom you shared a Coke. Or the pretty girl you kissed at the party that cold New Year’s Eve. If you caught the virus in this last scenario—as a teen or young adult—then Epstein-Barr may have triggered mono, or the “kissing disease,” in which a massive immune response against the pathogen causes weeks of sore throat, fever, and debilitating fatigue. For reasons poorly understood but not unique among viruses, Epstein-Barr virus, or EBV, hits harder the later you get it in life. If you first caught the virus as a baby or young child, as most people do, the initial infection was likely mild, if not asymptomatic. Unremarkable. And so this virus has managed to fly under the radar, despite infecting almost the entire globe. EBV is sometimes jokingly said to stand for “everybody’s virus.” Once inside the body, the virus hides inside your cells for the rest of your life, but it seems mostly benign. Except, except. In the decades since its discovery by the virologists Anthony Epstein and Yvonne Barr in 1964, the virus has been linked not only to mono but also quite definitively to cancers in the head and neck, blood, and stomach. It’s also been linked, more controversially, to several autoimmune disorders. Recently, the link to one autoimmune disorder got a lot stronger: Two separate studies published this year make the case—convincingly, experts say—that Epstein-Barr virus is a cause of multiple sclerosis, in which the body mistakenly attacks the nervous system. “When you mentioned the virus and MS 20 years ago, people were like, Get lost … It was a very negative attitude,” says Alberto Ascherio, an epidemiologist at Harvard and a lead author of one of those studies, which used 20 years of blood samples to show that getting infected with EBV massively increases the risk of developing multiple sclerosis. The connection between virus and disease is hard to dismiss now. But how is it that EBV causes such a huge range of outcomes, from a barely noticeable infection to chronic, life-altering illness? In the face of a novel coronavirus, my colleague Ed Yong noted that a bigger pandemic is a weirder pandemic: The sheer number of cases means that even one-in-a-million events become not uncommon. EBV is far from novel; it belongs to a family of viruses that were infecting our ancestors before they were really human. But it does infect nearly all of humanity and in rare occasions causes highly unusual outcomes. Its ubiquity manifests its weirdness. Decades after its discovery and probably millennia after those first ancient infections, we are still trying to understand how weird this old and familiar virus can be. We do little to curb the spread of Epstein-Barr right now. As the full scope of its consequences becomes clearer, will we eventually decide it’s worth stopping after all? From its very discovery, Epstein-Barr confounded our ideas of what a virus can or cannot do. The first person to suspect EBV’s existence was Denis Burkitt, a British surgeon in Uganda, who had the unorthodox idea that the unusual jaw tumors he kept seeing in young children were caused by a then-undiscovered pathogen. The tumors grew fast—doubling in size in 24 to 48 hours—and were full of white blood cells or lymphocytes turned cancerous. This disease became known as Burkitt’s lymphoma. Burkitt suspected a pathogen because the jaw tumors seemed to spread from area to neighboring area and followed seasonal patterns. In other words, this lymphoma looked like an epidemic. In 1963, a biopsy of cells from a girl with Burkitt’s lymphoma made its way to the lab of Anthony Epstein, in London. One of his students, Yvonne Barr, helped prepare the samples. Under the electron microscope, they saw the distinctive shape of a herpesvirus, a family that also includes the viruses behind genital herpes, cold sores, and chicken pox. And the tumor cells specifically were full of this virus. Case closed? Not yet. At the time, the idea that a virus could cause cancer was “rather remote,” says Alan Rickinson, a cancer researcher who worked in Epstein’s lab in the 1970s. “There was a great deal of skepticism.” What’s more, the virus’s ubiquity made things confusing. Critics pointed out that sure, children with Burkitt’s lymphoma had antibodies to EBV, but so did healthy children in Africa. So did American children for that matter, as well as isolated Icelandic farmers and people belonging to a remote tribe in the Brazilian rainforest. The virus was everywhere scientists looked, yet Burkitt’s lymphoma was largely confined to equatorial Africa. What if EBV was just an innocent bystander? Why wasn’t the virus causing disease anywhere else? It was. Scientists just didn’t know where to look until a stroke of luck clued them in. In 1967, a technician in a Philadelphia lab studying EBV and cancer fell ill with symptoms of mono. Because she was one of the few people who had tested negative for EBV antibodies, she had regularly donated blood for lab experiments that needed a known negative sample. When she came back after the illness, she started testing positive, highly positive. The timing suggested what we now know: EBV is the most common cause of mono....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Infectious mononucleosis in childhood, especially in adolescence, appeared to increase risk for an MS diagnosis, independent of shared familial factors, according to results of a population-based cohort study published in JAMA Network Open. “Infectious mononucleosis has previously been associated with MS, but it has been suggested that this is because people with genetic susceptibility to MS have an immune system that is more reactive to Epstein-Barr virus infection (the virus that causes infectious mononucleosis),” Scott Montgomery, PhD, director of clinical epidemiology and biostatistics at Örebro University Hospital in Sweden, told Healio Neurology. “This would mean that more severe infectious mononucleosis, possibly resulting in hospital admission, would be observed more often in people who would go on to develop MS anyway, irrespective of whether they had infectious mononucleosis or not. “It has also been argued that family circumstances in childhood might influence both infectious mononucleosis risk and MS risk, such that the infection is an epiphenomenon rather than a cause of MS,” Montgomery added. In the current study, Montgomery and colleagues sought to determine whether hospital-diagnosed infectious mononucleosis in childhood, adolescence or young adulthood was linked to subsequent MS diagnosis unrelated to shared familial factors. According to Montgomery, if infectious mononucleosis is indeed a risk factor for MS, comparing siblings would show this connection, and associations that arise entirely from shared familial characteristics would not appear. The researchers analyzed data of 2,492,980 individuals (52.63% men) included in the Swedish Total Population Register who were born in Sweden between 1958 and 1994. Follow-up occurred among participants beginning at age 20 years in 1978 and continued until 2018, with a median follow-up of 15.38 years. Infectious mononucleosis diagnosis before age 25 years served as the exposure. MS diagnoses from age 20 years served as the main outcome. Montgomery and colleagues used conventional and stratified Cox proportional hazards regression to address familial environmental or genetic confounding and, in turn, estimate the risk for an MS diagnosis linked to infectious mononucleosis from childhood, adolescence and early adulthood. Results showed an MS diagnosis among 5,867 (0.24%) participants from age 20 years (median age, 31.5 years). Infectious mononucleosis in childhood (HR = 1.98; 95% CI, 1.21-3.23) and adolescence (HR = 3; 95% CI, 2.48-3.63) correlated with an increased risk for an MS diagnosis. This risk remained significant after controlling for shared familial factors in stratified Cox proportional hazards regression. Infectious mononucleosis in early adulthood also correlated with risk for a subsequent MS diagnosis (HR = 1.89; 95% CI, 1.18-3.05); however, controlling for shared familial factors attenuated this risk and made it nonsignificant (HR = 1.51; 95% CI, 0.82-2.76). “MS should be considered as a potential diagnosis at an earlier time in patients with neurological symptoms and signs and a history of infectious mononucleosis in adolescence,” Montgomery said. “Although only a small proportion of those who have severe infectious mononucleosis in adolescence will go on to develop MS, limiting acute CNS involvement may have long-term benefits for this minority.” Original findings published in JAMA Network Open (October 11, 2021):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Infections with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the most common member of the herpes virus family, may contribute to the development of Sjögren’s syndrome by increasing the proportion of immune cells with autoimmune functions, a recent study suggests. Therapies targeting the interaction between EBV and activated immune cells may be useful in the clinic, the scientists said. The study, “Association between EBV serological patterns and lymphocytic profile of SjS patients support a virally triggered autoimmune epithelitis,” was published in the journal Nature, Scientific Reports. Sjögren’s syndrome, which predominantly affects middle-aged women, is characterized by mistaken immune attacks on the tear and salivary glands by cells known as lymphocytes, leading to disease symptoms. The two main types of lymphocytes, B-cells and T-cells, are normally involved in fighting infections from foreign pathogens such as bacteria and parasites. In Sjögren’s, however, evidence suggests that an infection may cause T-cells to enter the salivary and tear glands and support the disease-causing hyperactivity of B-cells, which are responsible for generating self-antibodies. Recently, follicular helper T-cells (Tfh) have been suggested to play a role in Sjögren’s development because they are found in higher levels in the bloodstream of Sjögren’s patients and are a major source of the immune signaling protein interleukin (IL)-21, which regulates B-cell survival. Furthermore, Tfh cells can express a receptor called CXCR5, which induces their migration toward B-cell sites. This receptor also has been found on a subset of cytotoxic (CD8+) T-cells thought to be involved in Sjögren’s by regulating B-cell responses and abnormal antibody production. While the underlying causes of Sjögren’s are still unclear, infection with EBV is a candidate for triggering the disease. Nevertheless, the impact of EBV infection on the B-cell profile found in Sjögren’s patients needs further examination. Now, a team of scientists based at the Comprehensive Health Research Centre, in Portugal, investigated subsets of B- and T-cells circulating in the bloodstream of Sjögren’s patients and assessed their relation to EBV infection. The study involved 57 people with Sjögren’s, of which 98.2% were women, with a median age of 60.6 years, and a median disease duration of 11.3 years. A group of 20 people with the autoimmune disorder rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and 24 healthy people (controls) also were enrolled for comparison. Compared with the healthy controls, the Sjögren’s patients had fewer helper T-cell numbers and percentages. The number of Tfh cells expressing CXCR5 was lower in Sjögren’s than in controls and RA patients. In contrast, the percentage of helper T-cells secreting IL-21 significantly increased in Sjögren’s participants compared with both RA patients and controls. Moreover, there was a significant correlation between higher IL-21-secreting T-cells and more Tfh cells with CXCR5. Cytotoxic T-cell percentages were significantly elevated in Sjögren’s compared with controls, but not in overall numbers. In comparison with both controls and RA patients, cytotoxic T-cells secreting IL-21 were increased as well. Higher levels of cytotoxic T-cells that express CXCR5 correlated with more disease activity, as assessed with the EULAR Sjögren’s disease activity index (ESSDAI), “suggesting their relevant role” in disease development, the team wrote. The percentages of non-activated B-cells (naïve) were significantly higher in Sjögren’s patients when compared with healthy controls and RA patients, and also presented higher absolute counts compared with RA, as “previously reported in the literature,” the team added. Next, the researchers divided patients into three subgroups according to their EBV profile, including those with previous infection, recent infection and EBV reactivation, or no evidence of active infection. Sjögren’s participants with recent infection or EBV reactivation had earlier disease onset and shorter disease duration. A majority of patients with a previous infection and/or a recent infection/reactivation had active disease at the time of recruitment, but patients with a previous infection showed higher disease activity scores. In contrast, the lowest disease activity scores were found in patients without active EBV infection. Regarding T-cells, patients with a previous infection and recent infection/activation had increased Tfh cells expressing CXCR5 as compared with those without active infection. The subset of B-cells that make antibodies also was increased in patients with a previous infection or recent infection/activation, compared with those without active EBV infection. “Our results suggest EBV-infection contributes to B- and T-cell differentiation towards the effector [cells] typical of [Sjögren’s syndrome],” the investigators wrote. “Considering the possible pathogenic role of EBV in the [development] of [Sjögren’s syndrome], therapies directed towards the interaction between EBV and activated effector T-cells and B-cells could halt the EBV-triggered lymphocytic activation, and have a relevant clinical applicability,” they added. Findings publshed in Nature Reports (Feb 18, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83550-0

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is very widespread. More than 90 percent of the world's population is infected, with varying consequences. Although the infection does not usually affect people, in some, it can cause glandular fever or various types of cancer. Researchers at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) have now discovered why different virus strains cause very divergent courses of disease. More than 90 percent of all people become infected with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) during their lifetime. The infection usually remains undetected. However, the virus can also cause diseases—with regional differences: Glandular fever (infectious mononucleosis) primarily occurs in Europe and North America, and normally affects adolescents or young adults. In equatorial Africa, Burkitt lymphoma is associated with EBV infection. And in Taiwan, southern China and Southeast Asia, the virus often causes nasopharyngeal carcinomas, cancers of the nose and throat area. This is one of the most common types of cancer in young adults in these countries. "Nasopharyngeal carcinomas are sometimes seen here too, but really very rarely," commented Henri-Jacques Delecluse from DKFZ. So how does EBV cause completely different diseases in different parts of the world? "One possible explanation is that different types of virus are responsible," Delecluse explained. "And we have now found evidence of precisely that." The DKFZ researchers are publishing their results in the journal Nature Microbiology. In the laboratory, Delecluse and his team studied a virus strain that had previously been isolated from a nasopharyngeal carcinoma. M81, as this particular type of virus is called, has certain peculiarities. The researchers had previously discovered that M81 infects not only the immune system's B cells, but also epithelial cells of the nasal mucous membrane very efficiently. In contrast, virus strains that cause glandular fever in Europe almost only infect B cells. And although the virus strains that are common there cause the infected B cells to multiply in a Petri dish, they do not produce any new virus particles, unlike M81. To find out how this variant affects the behavior of the virus, the DKFZ researchers used molecular biology tools to extract EBER2 from the M81 genome. "The virus was, indeed, no longer able to multiply in the infected cells," Delecluse noted. Even when an EBER2 element from a virus strain that is widespread in Europe was inserted into the M81 virus, it was no longer able to produce virus particles. "We have therefore finally found evidence that different types of virus can be responsible for different diseases," said Delecluse, emphasizing the significance of his results. "This finding is a strong argument for pressing on with vaccine research in order to develop protection against the most dangerous strains of EBV in future," he concluded. The vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV), which can cause cervical cancer, already uses a similar principle. Findings published in September 9, 2019 in Nature Microbiology: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0546-y

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

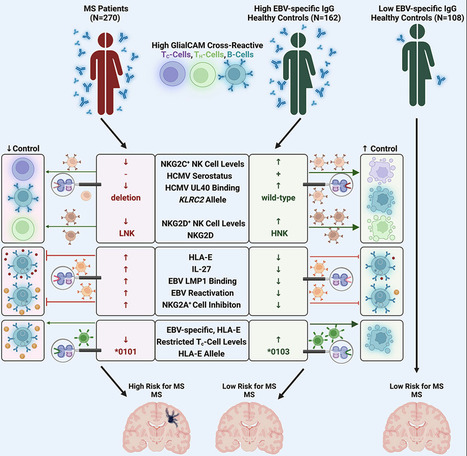

Highlights - Control of autoimmunity by NKG2C+ NK cell responses is severely impaired in MS patients

- MS-patient-derived GlialCAM-specific cells evade control via inhibitory HLA-E/NKG2A axis

- MS patients are predominantly infected with EBV variants that highly upregulate HLA-E

- Specific cytotoxic T cell responses can control EBV-infected GlialCAM-specific B cells

Summary Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a demyelinating disease of the CNS. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) contributes to the MS pathogenesis because high levels of EBV EBNA386–405-specific antibodies cross react with the CNS-derived GlialCAM370–389. However, it is unclear why only some individuals with such high autoreactive antibody titers develop MS. Here, we show that autoreactive cells are eliminated by distinct immune responses, which are determined by genetic variations of the host, as well as of the infecting EBV and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV). We demonstrate that potent cytotoxic NKG2C+ and NKG2D+ natural killer (NK) cells and distinct EBV-specific T cell responses kill autoreactive GlialCAM370–389-specific cells. Furthermore, immune evasion of these autoreactive cells was induced by EBV-variant-specific upregulation of the immunomodulatory HLA-E. These defined virus and host genetic pre-dispositions are associated with an up to 260-fold increased risk of MS. Our findings thus allow the early identification of patients at risk for MS and suggest additional therapeutic options against MS. Published in Cell (December 12, 2023):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Little is known on the landscape of viruses that reside within our cells, nor on the interplay with the host imperative for their persistence. Yet, a lifetime of interactions conceivably have an imprint on our physiology and immune phenotype. In this work, we revealed the genetic make-up and unique composition of the known eukaryotic human DNA virome in nine organs (colon, liver, lung, heart, brain, kidney, skin, blood, hair) of 31 Finnish individuals. By integration of quantitative (qPCR) and qualitative (hybrid-capture sequencing) analysis, we identified the DNAs of 17 species, primarily herpes-, parvo-, papilloma- and anello-viruses (>80% prevalence), typically persisting in low copies (mean 540 copies/ million cells). We assembled in total 70 viral genomes (>90% breadth coverage), distinct in each of the individuals, and identified high sequence homology across the organs. Moreover, we detected variations in virome composition in two individuals with underlying malignant conditions. Our findings reveal unprecedented prevalences of viral DNAs in human organs and provide a fundamental ground for the investigation of disease correlates. Our results from post-mortem tissues call for investigation of the crosstalk between human DNA viruses, the host, and other microbes, as it predictably has a significant impact on our health. Published (April 24, 2023)in Nucleic Acids Research: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad199

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Researchers found associations between certain viral illnesses and the risk of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurodegenerative diseases can damage different parts of the nervous system, including the brain. This may lead to problems with thinking, memory, and/or movement. Examples include Alzheimer’s disease (AD), multiple sclerosis (MS), and Parkinson’s disease (PD). These diseases tend to happen late in life. There are few effective treatments. Previous findings have suggested that viruses may play a role in certain neurodegenerative diseases. For example, a recent study found a link between Epstein-Barr virus infection and the risk of MS. There are also concerns about cognitive impacts from SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. A research team led by Drs. Mike Nalls, Kristin Levine, and Hampton Leonard of NIH's Center for Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias examined links between viruses and neurodegenerative disease more generally. To do so, they analyzed data from the FinnGen project. This is a repository of biomedical data, or biobank, from more than 300,000 people in Finland. The team searched the biobank for people who had been diagnosed with one of six different conditions: AD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), generalized dementia, vascular dementia, PD, and MS. They then checked how many had been hospitalized for a viral illness before. To confirm their findings, they looked for the same associations in the UK Biobank, which contains data from almost 500,000 people in the United Kingdom. Results appeared in Neuron on January 19, 2023. The researchers found 45 associations between viruses and neurodegenerative diseases in FinnGen. Of these, 22 also appeared in the UK Biobank. The strongest association was between viral encephalitis—brain inflammation caused by a virus—and AD. A person with viral encephalitis in the FinnGen database was 30 times as likely to be diagnosed with AD as someone without encephalitis. Results were similar in the UK Biobank; people with viral encephalitis were 22 times as likely to develop AD as those without. The team also found, in FinnGen, the association between Epstein-Barr virus and MS that was described before. The association wasn’t seen in the UK Biobank, but this may reflect how the different biobanks use hospital diagnostic codes; Epstein-Barr viruses are common and so often not noted. Influenza with pneumonia was associated with all the neurodegenerative diseases except MS. The researchers only included cases of influenza severe enough to need hospitalization in the study. Thus, these associations only apply to the most severe cases of influenza. FinnGen contains data on the same people over time. The team used this to examine how the associations depended on the time since infection. They found that some viral infections were associated with increased risk of neurodegenerative disease as much as 15 years later. The researchers note that vaccines exist for some of the viruses they identified. These include influenza, varicella-zoster (which causes chickenpox and shingles), and certain pneumonia-causing viruses. Vaccination might thus reduce some of the risk of the conditions they examined. “The results of this study provide researchers with several new critical pieces of the neurodegenerative disorder puzzle,” Nalls says. “In the future, we plan to use the latest data science tools to not only find more pieces but also help researchers understand how those pieces, including genes and other risk factors, fit together.”

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

“Long COVID” in some may not be an entirely new entity, researchers say. COVID can cause reservoirs of some viruses you’ve previously battled to reactivate, potentially leading to symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome—a condition that resembles long COVID, a recent study found. You had COVID a few months ago and recovered—but things still aren’t quite right. When you stand up, you feel dizzy, and your heart races. Even routine tasks leave you feeling spent. And what was once a good night’s sleep no longer feels refreshing. Long COVID, right? It may not be so simple. A mild or even an asymptomatic case of COVID can cause reservoirs of some viruses you’ve previously battled to reactivate, potentially leading to symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome—a condition that resembles long COVID, according to a recent study published in the journal Frontiers in Immunology. Researchers found herpes viruses like Epstein-Barr, one of the drivers behind mono, circulating in unvaccinated patients who had experienced COVID. In patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, antibody responses were stronger, signaling an immune system struggling to fight off the lingering viruses. Such non-COVID pathogens have been named as likely culprits behind chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis. The nebulous condition with no definitive cause leads to symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, dizziness when moving, and unrefreshing sleep. The symptoms of many long COVID patients could be described as chronic fatigue syndrome, experts say. Researchers in the October study hypothesized that COVID sometimes leads to suppression of the immune system, allowing latent viruses reactivated by the stress of COVID to recirculate—viruses linked to symptoms that are common in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and long COVID. Thus, “long COVID” in some may not be an entirely new entity, but another postviral illness—like ones seen in some patients after Ebola, the original SARS of 2003–2004, and other infections—that overlaps with chronic fatigue syndrome. As top U.S. infectious disease expert Dr. Anthony Fauci said in 2020, long COVID “very well might be a postviral syndrome associated with COVID-19.” ‘We’re still not doing that’ It’s possible that COVID is reactivating latent viruses in at least a portion of long COVID patients, causing chronic fatigue syndrome symptoms, Dr. Alba Miranda Azola, codirector of the long COVID clinic at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, told Fortune. But her clinic doesn’t check for the reactivation of viruses in long COVID patients. She doesn’t think the possibility of such viruses causing symptoms in patients is worth giving those patients antivirals or antibiotics, which can lead to undesirable side effects. “We don’t have enough evidence to support that treatment,” she said. Other physicians who have prescribed such treatments for long COVID patients, and those patients didn’t see much improvement, Azola added. She recently asked an infectious disease colleague if it was standard practice to test for, and treat, latent viruses in long COVID patients. “We’re still not doing that,” she recalled him saying. Dr. Nir Goldstein, a pulmonologist at National Jewish Health in Denver, who runs the hospital’s long COVID clinic, said it’s not yet clear what role latent viruses play in the long COVID. That’s because the nascent condition is such a complex and varied disorder. A consensus definition for long COVID hasn’t been universally agreed upon. Hundreds of possible symptoms have been identified, he points out—and no single explanation can account for them all. “There may be an association, but it’s very hard to know the causation,” Goldstein said. “It could be the other way around—it could be that long COVID causes reactivation, not that reactivation causes long COVID.” Dr. Panagis Galiasatos, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins’ pulmonary and critical care division who treats long COVID patients, doesn’t routinely test his patients for latent viruses, given that most respond well to treatments that his clinic uses. “If a patient doesn’t respond to treatment, maybe we’ll test for other things,” he said. There is a strong possibility that COVID is weakening the immune systems of “a good deal of people,” Galiasatos added. “I do think the immunodeficiency—when it’s there, it’s transient—allows those viruses to reemerge,” he said. Scientists are still unsure if viruses like Epstein-Barr merely initiate chronic fatigue syndrome or keep symptoms going, the October study points out. Similarly, researchers are still unsure what, if any, role latent viruses—including, potentially, SARS-CoV-2 itself—play in the development of long COVID. Few options, for now With so little known about both long COVID and chronic fatigue syndrome, it doesn’t really matter which a patient has, experts say—at least not right now. While the symptoms of both can be treated, there’s no specific drug for either because the cause—or causes—remain up in the air. “It’s the main reason why I don’t even order the test,” Azola said of antibody tests for possible latent viruses in long COVID patients. “There’s no treatment targeting chronic fatigue syndrome. There certainly are treatments that can help with symptom management and improve quality of life, but they’re not curative.” Delineating the two conditions could matter in the future, Goldstein said, if researchers can prove that the conditions are caused by residual viruses and develop a way to eradicate them. Azola has several patients who were diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome before COVID, after Epstein-Barr virus or H1N1 flu infections. They caught COVID, and now their chronic fatigue symptoms are much worse, she says. “They remember the things that worked for them before, learning how to pace themselves, staying out of what I call the corona-coaster—when they’re feeling good, doing a lot, then crashing for days,” she said. “They’re able to identify with that and implement strategies that have worked for them in the past.” Galiasatos, from Johns Hopkins, hopes that the new year brings long COVID breakthroughs, including a deeper understanding of the condition and tailored treatments—potentially by the end of 2023. Stanford University is recruiting for a study based on a theory similar to the one in the October study—that long COVID is caused by a lingering reservoir of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID, after acute infection. It will attempt to determine if the antiviral drug Paxlovid alleviates long COVID symptoms by reducing or eliminating that viral reservoir. “We’re starting to move into the trial-treatment phase slowly,” Azola said. Study Cited Published in Frontiers in Immunology: https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.949787

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A panel of investigational monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting different sites of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) blocked infection when tested in human cells in a laboratory setting. Moreover, one of the experimental mAbs provided nearly complete protection against EBV infection and lymphoma when tested in mice. The results appear online today in the journal Immunity. Scientists from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health, in collaboration with researchers from Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, led the study. EBV is one of the most common human viruses. After an EBV infection, the virus becomes dormant in the body but may reactivate in some cases. It is the primary cause of infectious mononucleosis and is associated with certain cancers, including Hodgkin lymphoma, and autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis. People with weakened immune systems, such as transplant recipients, are more likely than immunocompetent people to develop severe symptoms and complications from EBV infection. There is no licensed vaccine to protect against the virus. The researchers developed several investigational mAbs targeting two key proteins—gH and gL—found on EBV’s surface. The two proteins are known to facilitate EBV fusion with human cells and cause infection. When tested in the laboratory setting, the investigational mAbs prevented EBV infection of human B cells and epithelial cells, which line the throat at the initial site of EBV infection. Analyzing the structure of the mAbs and their two surface proteins using X-ray crystallography and advanced microscopy, the researchers identified multiple sites of vulnerability on the virus to target. When tested in mice, one of the experimental mAbs, called mAb 769B10, provided almost complete protection against EBV infection when given. The mAb also protected all mice tested from EBV lymphoma. The findings highlight viable EBV vaccine targets and the potential for the experimental mAbs to be used alone or in combination to prevent or treat EBV infection in immunocompromised patients most susceptible to severe EBV-related disease, according to the researchers. Additional research with mAb 769B10 is planned, the authors note. Research published in Immunity (Oct.27, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2022.10.003

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The jab could ward off Epstein-Barr virus, which causes glandular fever and is increasingly being linked to multiple sclerosis, lymphoma and stomach cancer. A vaccine that wards off the common Epstein-Barr virus to potentially prevent glandular fever, multiple sclerosis (MS) and even some cancers has shown promise in mice, ferrets and monkeys. A human trial is expected to start in 2023. Gary Nabel at ModeX Therapeutics in Natick, Massachusetts, and his colleagues developed a vaccine that exposes the body to two proteins that Epstein-Barr virus uses to invade cells, training the immune system to recognise the pathogen if exposed. Initial experiments have shown that mice, ferrets and rhesus macaques developed antibodies against Epstein-Barr virus post-vaccination. To better understand the jab’s potential in people, the researchers engineered mice with human-like immune systems. When exposed to Epstein-Barr virus, only 17 per cent of the mice became infected after receiving antibodies from other vaccinated rodents. In contrast, 100 per cent of the mice without antibodies became infected. “It was a very promising result because we were able to basically block the virus infection almost entirely and stop it from causing even low-level infection,” says Nabel. None of the mice that received the vaccine-induced antibodies developed lymphomas, cancers of the lymphatic system that are increasingly being linked to Epstein-Barr virus, compared with half of the unprotected rodents. The researchers didn’t look into any other Epstein-Barr-related conditions, such as stomach cancer. More than 95 per cent of adults worldwide are infected with Epstein-Barr virus, a type of herpes that most commonly spreads via saliva. It is known to cause glandular fever, also called “mono”, and is associated with MS. If the vaccine is shown to be safe and effective in people, it could be given to children to prevent Epstein-Barr-related conditions, says Nabel. Moderna, the US company better known for its covid-19 vaccine, recently began a clinical trial for its own Epstein-Barr jab. Moderna’s vaccine differs from the ModeX candidate in that, similarly to its covid-19 jab, it uses mRNA to instruct cells to make several Epstein-Barr virus proteins, rather than administering them directly. Julia Morahan at MS Australia says both vaccines look promising, but MS is a progressive disease and it will be several decades before we can gauge their potential. “If we were able to give every child a vaccine, we would then have to wait a solid 25 years to see if they develop MS,” she says. Original research published in Science Translational Medicine (May 4, 2022): 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf3685

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A connection between the human herpesvirus Epstein-Barr and multiple sclerosis (MS) has long been suspected but has been difficult to prove. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is the primary cause of mononucleosis and is so common that 95 percent of adults carry it. Unlike Epstein-Barr, MS, a devastating demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, is relatively rare. It affects 2.8 million people worldwide. But people who contract infectious mononucleosis are at slightly increased risk of developing MS. In the disease, inflammation damages the myelin sheath that insulates nerve cells, ultimately disrupting signals to and from the brain and causing a variety of symptoms, from numbness and pain to paralysis. To prove that infection with Epstein-Barr causes MS, however, a research study would have to show that people would not develop the disease if they were not first infected with the virus. A randomized trial to test such a hypothesis by purposely infecting thousands of people would of course be unethical. Instead researchers at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Medical School turned to what they call “an experiment of nature.” They used two decades of blood samples from more than 10 million young adults on active duty in the U.S. military (the samples were taken for routine HIV testing). About 5 percent of those individuals (several hundred thousand people) were negative for Epstein-Barr when they started military service, and 955 eventually developed MS. The researchers were able to compare the outcomes of those who were subsequently infected and those who were not. The results, published on September 13 in Science, show that the risk of multiple sclerosis increased 32-fold after infection with Epstein-Barr but not after infection with other viruses. “These findings cannot be explained by any known risk factor for MS and suggest EBV as the leading cause of MS,” the researchers wrote. In an accompanying commentary, immunologists William H. Robinson and Lawrence Steinman, both at Stanford University, wrote, “These findings provide compelling data that implicate EBV as the trigger for the development of MS.” Epidemiologist Alberto Ascherio, senior author of the new study, says, “The bottom line is almost: if you’re not infected with EBV, you don’t get MS. It’s rare to get such black-and-white results.” Virologist Jeffrey I. Cohen, who heads the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) at the National Institutes of Health and was not involved in the research, is cautious about claiming “cause.” He argues that it still must be shown that preventing Epstein-Barr prevents MS but agrees the results are dramatic. “When the original studies were done with cigarette smoking and lung cancer, they found a 25-fold risk factor for people who smoked more than 25 cigarettes a day,” Cohen says. “This is even higher.” Much of the world’s population, especially in developing countries, is infected with Epstein-Barr very early in life without much ill effect, although the virus can lead to several rare cancers. Everyone else is infected in adolescence and young adulthood, when Epstein-Barr usually leads to infectious mononucleosis, also called “kissing disease” because it is transmitted via saliva. After infection, Epstein-Barr lives on in some B cells of the immune system and the antibodies developed to fight it remain in the blood. In the new study, which is a much larger expansion of a 2010 investigation, the researchers analyzed up to three blood samples for each individual with MS: the first taken when most of the military personnel were under the age of 20, the last taken years later, before the onset of the disease, and one in between. The team was looking for seroconversion, or the appearance of antibodies in the blood as evidence of infection. Each person with MS was also matched with two randomly selected controls without MS, who were of the same age, sex, race or ethnicity, and branch of the military. Out of the 955 cases of MS, they were able to assemble appropriate samples for 801 individuals with the disease and 1,566 controls. Thirty-five of the people who developed MS and 107 controls tested negative for EBV initially. Only one of the 801 people with MS had not been infected with Epstein-Barr before the disease’s onset. The risk of developing MS was 32 times greater for those who seroconverted by the third sample, compared with those who did not. As for the one case of MS in someone who remained negative for Epstein-Barr, it is possible that person was infected after the sample was taken, but it is also true that, in diseases that are clinically defined by their symptoms, such as MS, it is highly unlikely that 100 percent of cases derive from the same cause, even if most do, Ascherio says. “The numbers are just so striking,” says Stephen Hauser, director of the University of California, San Francisco, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, who was not involved with the study. “It’s really a uniform seroconversion before the onset of MS that is really far more significant than in the control population.” But to be sure Epstein-Barr was the culprit, Ascherio and his colleagues also measured antibodies against cytomegalovirus, another herpesvirus, and found no difference in levels in those who developed MS and those who did not. Using a subset of 30 MS cases and 30 controls, they conducted a scan to detect antibody responses to most of the viruses that infect humans. Again, there was no difference. And to rule out the possibility that infection with Epstein-Barr preceded MS and not the other way around, the team also measured levels of a protein that is elevated in serum when neurons are injured or die and that therefore serves as a marker of the beginning of the pathological process before clinical symptoms appear. The protein levels only rose after Epstein-Barr infection. One major question remains, however: How does the virus lead to the disease? That is unknown and “elusive,” Robinson and Steinman wrote in their commentary. They proposed several possibilities, such as inducing an autoimmune reaction. Even if Epstein-Barr is the triggering event for MS, infection alone is insufficient for an actual diagnosis. Epstein-Barr, it appears, has to combine with a genetic predisposition and possibly environmental factors, such as smoking and vitamin D deficiency, to increase risk. Understanding the underlying mechanism will be important, the experts say. But meanwhile “this is the best epidemiologic lead we have in terms of the cause of MS,” Hauser says. Historically, we have thought of MS as an autoimmune disease of unknown etiology. “Now we should start thinking of MS as a complication of infection with the Epstein-Barr virus,” Ascherio says. “This should open a new chapter in trying to find a way to treat and prevent the disease.” Antivirals that target EBV in infected B cells are one possibility. One of the more exciting developments in MS in recent years was the success of B-cell-depletion therapies. In earlier work, Hauser and his colleagues found that the tissue damage in MS is primarily directed by B cells, which attack the myelin sheath protecting nerves. The therapies now approved for use are monoclonal antibodies that kill those B cells, thereby easing inflammation. They are not a cure but are highly effective against MS relapses, reducing the development of new lesions measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain by an astounding 99 percent. They are also the only therapies shown to be effective against primary progressive MS, a previously untreatable form of the disease. “One might be able to refine these therapies that are working well and maybe just target the EBV-infected B cells,” says immunologist Christian Münz of the University of Zurich, who was also not involved in the new Science study. Others are already working on vaccines that could prevent infection with Epstein-Barr. Moderna, which created an mRNA vaccine against COVID-19, launched a phase 1 trial of an mRNA vaccine for Epstein-Barr earlier this month. And NIAID’s Cohen expects to begin a phase 1 trial of another Epstein-Barr vaccine by the end of February. If these researchers succeed, such vaccines might dramatically reduce the incidence of mononucleosis and some cancers. And now it is conceivable that they could do the same for MS. Cited Findings Published in Science (Jan. 13, 2022): https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abj8222

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

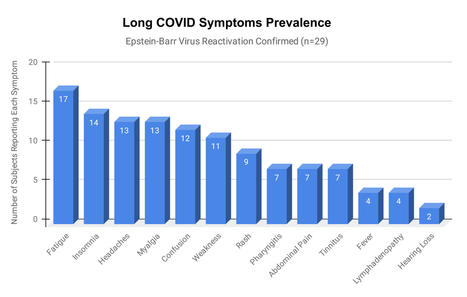

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation resulting from the inflammatory response to coronavirus infection may be the cause of previously unexplained long COVID symptoms—such as fatigue, brain fog, and rashes—that occur in approximately 30% of patients after recovery from initial COVID-19 infection. The first evidence linking EBV reactivation to long COVID, as well as an analysis of long COVID prevalence, is outlined in a new long COVID study published in the journal Pathogens. "We ran EBV antibody tests on recovered COVID-19 patients, comparing EBV reactivation rates of those with long COVID symptoms to those without long COVID symptoms," said lead study author Jeffrey E. Gold of World Organization. "The majority of those with long COVID symptoms were positive for EBV reactivation, yet only 10% of controls indicated reactivation." The researchers began by surveying 185 randomly selected patients recovered from COVID-19 and found that 30.3% had long term symptoms consistent with long COVID after initial recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection. This included several patients with initially asymptomatic COVID-19 cases who later went on to develop long COVID symptoms. The researchers then found, in a subset of 68 COVID-19 patients randomly selected from those surveyed, that 66.7% of long COVID subjects versus 10% of controls were positive for EBV reactivation based on positive EBV early antigen-diffuse (EA-D) IgG or EBV viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgM titers. The difference was significant (p < 0.001, Fisher's exact test). "We found similar rates of EBV reactivation in those who had long COVID symptoms for months, as in those with long COVID symptoms that began just weeks after testing positive for COVID-19," said coauthor David J. Hurley, Ph.D., a professor and molecular microbiologist at the University of Georgia. "This indicated to us that EBV reactivation likely occurs simultaneously or soon after COVID-19 infection." The relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and EBV reactivation described in this study opens up new possibilities for long COVID diagnosis and treatment. The researchers indicated that it may be prudent to test patients newly positive for COVID-19 for evidence of EBV reactivation indicated by positive EBV EA-D IgG, EBV VCA IgM, or serum EBV DNA tests. If patients show signs of EBV reactivation, they can be treated early to reduce the intensity and duration of EBV replication, which may help inhibit the development of long COVID. "As evidence mounts supporting a role for EBV reactivation in the clinical manifestation of acute COVID-19, this study further implicates EBV in the development of long COVID," said Lawrence S. Young, Ph.D., a virologist at the University of Warwick, and Editor-in-Chief of Pathogens. "If a direct role for EBV reactivation in long COVID is supported by further studies, this would provide opportunities to improve the rational diagnosis of this condition and to consider the therapeutic value of anti-herpesvirus agents such as ganciclovir." Original findings published in Pathogens (June 10, 2021): https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10060763

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Tailored T-cells specially designed to combat a half dozen viruses are safe and may be effective in preventing and treating multiple viral infections, according to research led by Children's National Hospital faculty. Catherine Bollard, M.B.Ch.B., M.D., director of the Center for Cancer and Immunology Research at Children's National and the study's senior author, presented the teams' findings Nov. 8, 2019, during a second-annual symposium jointly held by Children's National and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Children's National and NIAID formed a research partnership in 2017 to develop and conduct collaborative clinical research studies focused on young children with allergic, immunologic, infectious and inflammatory diseases. Each year, they co-host a symposium to exchange their latest research findings. According to the NIH, more than 200 forms of primary immune deficiency diseases impact about 500,000 people in the U.S. These rare, genetic diseases so impair the person's immune system that they experience repeated and sometimes rare infections that can be life threatening. After a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, brand new stem cells can rebuild the person's missing or impaired immune system. However, during the window in which the immune system rebuilds, patients can be vulnerable to a host of viral infections. Because viral infections can be controlled by T-cells, the body's infection-fighting white blood cells, the Children's National first-in-humans Phase 1 dose escalation trial aimed to determine the safety of T-cells with antiviral activity against a half dozen opportunistic viruses: adenovirus, BK virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Human Herpesvirus 6 and human parainfluenza-3 (HPIV3). Eight patients received the hexa-valent, virus-specific T-cells after their stem cell transplants: - Three patients were treated for active CMV, and the T-cells resolved their viremia.

- Two patients treated for active BK virus had complete symptom resolution, while one had hemorrhagic cystitis resolved but had fluctuating viral loads in their blood and urine.

- Of two patients treated prophylactically, one developed EBV viremia that was treated with rituximab.

Two additional patients received the T-cell treatments under expanded access for emergency treatment, one for disseminated adenoviremia and the other for HPIV3 pneumonia. While these critically ill patients had partial clinical improvement, they were being treated with steroids which may have dampened their antiviral responses. "These preliminary results show that hexaviral-specific, virus-specific T-cells are safe and may be effective in preventing and treating multiple viral infections. Of note, enzyme-linked immune absorbent spot assays showed evidence of antiviral T-cell activity by three months post infusion in three of four patients who could be evaluated and expansion was detectable in two patients." Michael Keller, M.D., pediatric immunologist at Children's National and the lead study author.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Latent herpes virus reactivation has been documented in more than half of astronauts during space shuttle and International Space Station missions, and according to a recent study funded by NASA, the cause is stress.“Herpes virus is a broad category of viruses, beyond the small subset that cause sexually transmitted diseases.Most humans become infected early in life with one or more, and never fully clear these viruses,” Satish Mehta, PhD, senior scientist in the immunology/virology lab at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, told Infectious Disease News. Results showed that 47 out of 89 (53%) astronauts on short space shuttle flights, and 14 out of 23 (61%) on longer space station missions shed herpes viruses in their saliva or urine samples. According to the study, astronauts shed four of the eight major human herpes viruses: Epstein-Barr, varicella-zoster and herpes simplex-1 in saliva and cytomegalovirus in urine. The researchers said most astronauts were asymptomatic, with only six developing symptoms. “Larger quantities and increased frequencies for these viruses were found during spaceflight as compared to before or after flight samples and their matched healthy controls,” Mehta and colleagues wrote. Mehta explained why: “[The] short answer is stress. In people with reduced immunity, such as the elderly or stressed individuals, these viruses can awaken and cause disease,” he said. “Although NASA believes there is no clinical risk to astronauts during orbital spaceflight, there is concern that during deep space exploration missions, there may be clinical risks related to viral shedding. Although we do not have a serious clinical problem related to herpes viruses, their reactivation is an excellent ‘flag,’ or biomarker, for stress and reduced immunity.” In the study, Mehta and colleagues noted that continued viral shedding after a flight can pose a potential risk for crew who may encounter infants, seronegative adults or immunocompromised people, so protocols have been put in place. The study was published in February 2019 in Frontiers in Microbiology - Virology: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00016

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...