Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

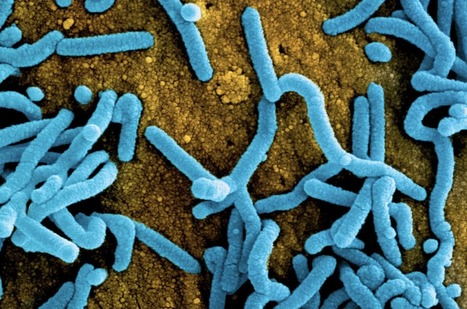

Filoviruses frequently emerge to cause terrifying outbreaks of often-fatal human disease. Treatment options so far have focused on monoclonal antibodies. Remdesivir is an adenosine analog that binds viral RNA polymerase to block replication by premature termination of RNA transcription. The drug has been successfully used intravenously for treating progressive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections in humans. Cross et al. tested a related oral prodrug, obeldesivir (currently in phase 3 clinical trials for COVID-19 treatment), in nonhuman primates for its therapeutic value against filoviruses (see the Perspective by Sprecher and Van Herp). When administered to the animals within 24 hours of virus exposure once daily for 10 days, the drug conferred complete protection against lethal infection with Sudan ebolavirus. Having an oral drug would be a major logistical advantage for use in the remote, resource-poor areas where filoviruses occur. —Caroline Ash Published in Science (March 15, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adk6176

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The Antiviral Program for Pandemics (APP) team, along with experts from across the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), has drafted Target Product Profiles (TPPs) for potential direct-acting antiviral therapeutics candidates targeting several key viruses of pandemic potential. These TPPs should be considered ‘living documents’ that are never final but may be useful starting points for consideration by therapeutics developers who are drafting TPPs for their specific candidates. Also, the example TPPs are not intended to provide details about product requirements for funding or other support from USG or other funders. Instead, these sample TPPs are being provided as tools for scientists working toward therapeutics product development of direct-acting antivirals for use in potential future outbreaks or pandemics. We are happy to receive feedback on these sample TPPs and may make updates/revisions or add TPPs for additional clinical indications in the future, so please monitor this page for updates and send any feedback to APPSubmissions@mail.nih.gov

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Africa is grappling with not one, but two outbreaks of Marburg fever, a disease that causes symptoms and a death rate comparable to Ebola, its viral cousin. Health officials in Tanzania announced Tuesday that they had confirmed the country’s first-ever Marburg outbreak, involving at least eight people so far, five of whom have died. One of the people who died is a health care worker. Across the continent, Equatorial Guinea has been combating its first-ever Marburg outbreak for several weeks now, though in an unusual turn of events for a viral hemorrhagic fever outbreak, scant information has been shared with the international community. The last update from the World Health Organization on that outbreak was issued nearly a month ago, on Feb. 25. Tanzanian Health Minister Ummy Mwalimu announced that the country’s national public health laboratory had confirmed that Marburg was the cause of an outbreak that was first reported last week. Five members of a single family are among the cases. At least 161 people who have been in contact with the cases have been identified and are being monitored. “We are working with the government to rapidly scale up control measures to halt the spread of the virus and end the outbreak as soon as possible,” Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO’s regional director for Africa, said in a statement. Moeti noted that while Tanzania has not previously battled Marburg, it has coped with a number of health emergencies in recent years, including Covid-19, cholera, and dengue fever. “The lessons learnt, and progress made during other recent outbreaks should stand the country in good stead as it confronts this latest challenge,” she said.But Gary Kobinger, a veteran of numerous Ebola and Marburg responses, questioned that line of thinking, and urged the two countries to both be transparent and to accept outside help. “Managing a filovirus outbreak is completely different than a typical emergence of let’s say cholera or measles or even Rift Valley fever,” said Kobinger, who is director of the Galveston National Laboratory at the University of Texas Medical Branch. Marburg and Ebola viruses are both filoviruses. Kobinger said that even countries that have experience with these viruses struggle sometimes to contain outbreaks. “You need to act very fast. The first two weeks, three weeks are extremely important. And this is where you’re going to define the evolution of the outbreak,” he told STAT. “If you lose control of a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, which happens, that’s one thing. If you lose control of an Ebola outbreak or a Marburg outbreak, you have a different problem on your hands.” Viral hemorrhagic fever outbreaks pose significant and unique challenges, because of their death rates, which are generally in the high double digits. These diseases spark panic in the communities in which they spread at the very time when community cooperation is essential to stop transmission. “People are scared. One case in one village will shut down the place. And people will not want to go there and people that come out of there will be treated as if they are infected, potentially,” Kobinger said. “So it’s very difficult in terms of trade, in terms of social movement, in terms of social acceptance. It’s much more traumatic than Covid or something else.”bHistorically Marburg outbreaks have been smaller than Ebola outbreaks; there have been none that involved thousands of cases, like the Ebola outbreaks in West Africa (2014-2016) or in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2018-2020). But in 2004-2005, 252 people were infected in an outbreak in Angola, with 227 or 90% of them dying. There are no licensed vaccines to protect against Marburg and no approved drugs. A WHO-led meeting in mid-February convened to explore whether there were supplies of experimental vaccines or drugs that could be tested in the Equatorial Guinea outbreak found there are few doses available to test. The outbreak in Equatorial Guinea dates back to at least early January; by late February, nine cases — one confirmed, four probable and four suspected — had been identified. It is not unusual to see probable and suspected cases in a viral hemorrhagic fever outbreak, especially in the early days. People die and are buried without a diagnosis. Even after authorities realize what they are dealing with and testing protocols are established, some families hide their dead so as to be able to perform burial rituals which, while important culturally, serve to spread the virus further. It is believed additional cases have been identified in Equatorial Guinea, but the country’s leadership has been unwilling to disclose the information.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Some of the most fragile health systems in the world can teach us ways to respond to public health threats early and effectively. Stephanie Nolen, a global health reporter, has reported on pandemics around the world, including H.I.V., cholera and yellow fever. When Ebola swept through the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo in 2018, it was a struggle to track cases. Dr. Billy Yumaine, a public health official, recalls steady flows of people moving back and forth across the border with Uganda while others hid sick family members in their homes because they feared the authorities. It took at least a week to get test results, and health officials had difficulty isolating sick people while they waited. It took two years for the country to bring that outbreak under control, and more than 2,300 people died. A similar disaster threatened the D.R.C. last September. Members of a family in North Kivu Province fell ill with fevers, vomiting and diarrhea, one after the other. Then their neighbors became sick, too. But that set off a series of steps that the D.R.C. put in place after the 2018 outbreak. The patients were tested, the cases were quickly confirmed as a new outbreak of Ebola and, right away, health workers traced 50 contacts of the families. Then they fanned out to test possible patients at health centers and screened people at the busy border posts, stopping anyone with symptoms of the hemorrhagic fever. Local labs that had been set up in the wake of the previous outbreak tested more than 1,800 blood samples. It made a difference: This time, Ebola claimed just 11 lives. “Those people died, but we kept it to 11 deaths, where in the past we lost thousands,” Dr. Yumaine said. You probably didn’t hear that story. You probably didn’t hear about the outbreak of deadly Nipah virus that a doctor and her colleagues stopped in southern India last year, either. Or the rabies outbreak that threatened to race through nomadic Masai communities in Tanzania. Quick-thinking public health officials brought it in check after a handful of children died. Over the past couple of years, the headlines and the social feeds have been dominated by outbreaks around the world. There was Covid, of course, but also mpox (formerly known as monkeypox), cholera and resurgent polio and measles. But a dozen more outbreaks flickered, threatened — and then were snuffed out. While it may not feel that way, we have learned a thing or two about how to do this, and, sometimes, we get it right. A report by the global health strategy organization Resolve to Save Lives documented six disasters that weren’t. All emerged in developing countries, including those that, like the D.R.C., have some of the most fragile health systems on earth. While cutting-edge vaccine technology and genomic sequencing have received lots of attention in the Covid years, the interventions that helped prevent these six pandemics were steadfastly unglamorous: building the trust of communities in the local health system. Training local staff in how to report a suspected problem effectively. Making sure funds are available to dispense swiftly, to deploy contact tracers or vaccinate a village against rabies. Increasing lab capacity in areas far from the main urban centers. Priming everyone to move fast at the first sign of potential calamity. “Outbreaks don’t occur because of a single failure, they occur because of a series of failures,” said Dr. Tom Frieden, the chief executive of Resolve and a former director of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “And the epidemics that don’t happen don’t happen because there are a series of barriers that will prevent them from happening. ” Dr. Yumaine told me that a key step that made a difference in shutting down Congo’s Ebola outbreak in 2021 was having local health officials in each community trained in the response. The Kivu region has lived through decades of armed conflict and insecurity, and its population faces a near-constant threat of displacement. In previous public health emergencies, when people were told they would have to isolate because of Ebola exposure, they feared it was a trick to move them off their land. “In the past, it was always people from Kinshasa who were coming with these messages,” he said, referring to the country’s capital. But this time, the instructions about lockdowns and isolation came from trusted sources, so people were more willing to listen and be tested. “We could give local control to local people because they were trained,” he said. Because labs had been set up in the region, people with suspected Ebola could be tested in a day — two, at most — instead of waiting a week or more for samples to be sent more than 1,600 miles to Kinshasa. In the State of Kerala in southern India, Dr. Chandni Sajeevan, the head of emergency medicine at Kozhikode Government Medical College hospital, led the response to an outbreak of Nipah, a virus carried by fruit bats, in 2018. Seventeen of the 18 people infected died, including a young trainee nurse who cared for the first victims. “It was something very frightening,” Dr. Chandni said. The hospital staff got a crash course in intensive infection control, dressing up in the “moon suits” that seemed so foreign in the pre-Covid era. Nurses were distraught over the loss of their colleague. Three years later, in 2021, Dr. Chandni and her team were relieved when the bat breeding season passed with no infections. And then, in May, deep into India’s terrible Covid wave, a 12-year-old boy with a high fever was brought to a clinic by his parents. That clinic was full, so he was sent to the next, and then to a third, where he tested negative for Covid. But an alert clinician noticed that the child had developed encephalitis. He sent a sample to the national virology lab. It swiftly confirmed that this was a new case of Nipah virus. By then, the child could have exposed several hundred people, including dozens of health workers. The system Dr. Chandni and her colleagues had put in place after the 2018 outbreak kicked into gear: isolation centers, moon suits, testing anyone with a fever for Nipah as well as Covid. She held daily news briefings to quell rumors and keep the public on the lookout for people who might be ill — and away from bats and their droppings, which litter coconut groves where children play. Teams were sent out to catch bats for surveillance. Everyone who had been exposed to the sick boy was put into 21 days of quarantine. “Everyone, ambulance drivers, elevator operators, security guards — this time, they knew about Nipah and how to behave not to spread it,” she said. Amanda McLelland, who leads epidemic prevention at Resolve, told me that when she heard of new Ebola cases in Guinea in West Africa in 2021, she feared disaster. An outbreak that began in Guinea in 2014 had spread to two neighboring countries, and by the time it was declared over two years later, nearly 30,000 people had been infected and 11,325 had died. But this time, although Guinea was already struggling to respond to Covid, it managed to bring the Ebola outbreak in check in six months, with just 11 deaths. “That was a fantastic example of learning those lessons and investing and building sustainably in the capacity,” Ms. McLelland said. It should be celebrated, she added. While public health failures, such as those in the face of Covid, receive plenty of attention, she said, “our success is invisible.” Nevertheless, progress can be fitful: A new Ebola outbreak is slowly being brought under control in Uganda, and neighboring nations have watched it with concern. Dr. Frieden said he was discouraged to see this, because Uganda has a strong public health system with a track record of detecting and responding to outbreaks quickly. “I think what we’re seeing there is the unfortunate harvest of Covid. Covid broke a lot of things,” he said. “It broke health care worker resilience, it broke the willingness of many people to follow public health advice, it broke trust in the health care system and communities that was there before. Progress is possible, but it’s also fragile.” But Dr. Yumaine said he had growing confidence that even if Ebola were to spill back across the border from Uganda, the D.R.C. could respond swiftly, with surveillance systems that grow better all the time. “We’re encouraged by our improvements,” he said. “But we’re not stopping there.”

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

17 July 2022 Accra/Brazzaville - Ghana has announced the country’s first outbreak of Marburg virus disease, after a World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre laboratory confirmed earlier results. The Institut Pasteur in Dakar, Senegal received samples from each of the two patients from the southern Ashanti region of Ghana – both deceased and unrelated – who showed symptoms including diarrhoea, fever, nausea and vomiting. The laboratory corroborated the results from the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, which suggested their illness was due to the Marburg virus. One case was a 26-year-old male who checked into a hospital on 26 June 2022 and died on 27 June. The second case was a 51 -year-old male who reported to the hospital on 28 June and died on the same day. Both cases sought treatment at the same hospital within days of each other. WHO has been supporting a joint national investigative team in the Ashanti Region as well as Ghana’s health authorities by deploying experts, making available personal protective equipment, bolstering disease surveillance, testing, tracing contacts and working with communities to alert and educate them about the risks and dangers of the disease, and to collaborate with the emergency response teams. In addition, a team of WHO experts will be deployed over the next couple of days to provide coordination, risk assessment and infection prevention measures. “Health authorities have responded swiftly, getting a head start preparing for a possible outbreak. This is good because without immediate and decisive action, Marburg can easily get out of hand. WHO is on the ground supporting health authorities and now that the outbreak is declared, we are marshalling more resources for the response,” said Dr Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa. More than 90 contacts, including health workers and community members, have been identified and are being monitored. Marburg is a highly infectious viral haemorrhagic fever in the same family as the more well-known Ebola virus disease. It is only the second time the zoonotic disease has been detected in West Africa. Guinea confirmed a single case in an outbreak that was declared over on 16 September 2021, five weeks after the initial case was detected. Previous outbreaks and sporadic cases of Marburg in Africa have been reported in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, South Africa and Uganda. WHO has reached out to neighbouring high-risk countries and they are on alert. Marburg is transmitted to people from fruit bats and spreads among humans through direct contact with the bodily fluids of infected people, surfaces and materials. Illness begins abruptly, with high fever, severe headache and malaise. Many patients develop severe haemorrhagic signs within seven days. Case fatality rates have varied from 24% to 88% in past outbreaks depending on virus strain and the quality of case management. Although there are no vaccines or antiviral treatments approved to treat the virus, supportive care – rehydration with oral or intravenous fluids – and treatment of specific symptoms, improves survival. A range of potential treatments, including blood products, immune therapies and drug therapies, as well as candidate vaccines with phase 1 data are being evaluated.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A second Ebola patient has died in northwestern Democratic Republic of Congo, the World Health Organization (WHO) said on Tuesday, days into a fresh outbreak of the deadly disease. Genetic testing showed an infection confirmed last week in the city of Mbandaka was a new "spillover event", a transmission from an infected animal, and not linked to any previous outbreaks, said the country's National Institute of Biomedical Research. The second fatality was a 25-year-old woman who was the sister-in-law of the first case, the WHO said on Twitter. She began experiencing symptoms 12 days earlier, it said. The first patient began showing symptoms on April 5, but did not seek treatment for more than a week. He died in an Ebola treatment centre on April 21. The lag time has health workers rushing to identify contacts who may have been infected, the WHO said. At least 145 people came into contact with the confirmed cases and their health is being closely monitored, the WHO said, noting later that one of the first cases was a health worker. Mbandaka, a trading hub on the banks of the Congo River, is a city of over one million where people live in close proximity with road, water and air links to the capital Kinshasa. WHO emergencies director for Africa, Ibrahima Soce Fall, said there was a risk the disease could spread to neighbouring Central African Republic and Congo Brazzaville. "This is concerning but taking into account the capacity build up and experience in Congo we believe it can be contained," Fall said at a press conference in Geneva. Congo has seen 13 previous outbreaks of Ebola, including one in 2018-2020 in the east that killed nearly 2,300 people, the second highest toll recorded in the history of the hemorrhagic fever. The most recent outbreak ended in December in the east after six deaths. Mbandaka, the capital of Equateur province, has also contended with two previous outbreaks - in 2018 and in 2020. The country's equatorial forests are a natural reservoir for the Ebola virus, which was discovered near the Ebola River in northern Congo in 1976.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A new technology aims to stop wildlife from spreading Ebola, rabies, and other viruses. It could prevent the next pandemic by stopping pathogens from jumping from animals to people. Imagine a cure that’s as contagious as the disease it fights—a vaccine that could replicate in a host’s body and spread to others nearby, quickly and easily protecting a whole population from microbial attacks. That’s the goal of several teams around the world who are reviving controversial research to develop self-spreading vaccines. Their hope is to reduce infectious disease transmission among wild animals, thereby lowering the risk that harmful viruses and bacteria can jump from wildlife to humans as many experts believe happened with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 60 percent of all known infectious diseases and 75 percent of new or emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic. Scientists cannot predict why, when, or how new zoonotic diseases will emerge. But when they do, these diseases are often deadly and costly to control. What’s more, many researchers predict that climate change, biodiversity loss, and population growth will accelerate their spread. Vaccines are a key tool for preventing diseases from spreading, but wild animals are difficult to vaccinate because each one must be located, captured, vaccinated, and released. Self-spreading vaccines offer a solution. Advances in genomic technology and virology, and a better understanding of disease transmission, have accelerated work that began in the 1980s to make genetically engineered viruses that spread from one animal to another, imparting immunity to disease rather than infection. Researchers are currently developing self-spreading vaccines for Ebola, bovine tuberculosis, and Lassa fever, a viral disease spread by rats that causes upward of 300,000 infections annually in parts of West Africa. The approach could be expanded to target other zoonotic diseases, including rabies, West Nile virus, Lyme disease, and the plague. Advocates for self-spreading vaccines say they could revolutionize public health by disrupting infectious disease spread among animals before a zoonotic spillover could occur—potentially preventing the next pandemic. But others argue that the viruses used in these vaccines could themselves mutate, jump species, or set off a chain reaction with devastating effects across entire ecosystems. “Once you set something engineered and self-transmissible out into nature, you don't know what happens to it and where it will go,” says Jonas Sandbrink, a biosecurity researcher at the University of Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute. “Even if you just start by setting it out into animal populations, part of the genetic elements might find their way back into humans.” The first, and only, self-spreading vaccine field trial In 1999, veterinarian José Manuel Sánchez-Vizcaíno led a team of researchers to Isla del Aire, an island off the eastern coast of Spain, to test a self-spreading vaccine against two viral diseases: rabbit hemorrhagic disease and myxomatosis. Although neither disease infects humans, at the time they both had been decimating domestic and wild rabbit populations across China and Europe for several decades. Traditional vaccines for both diseases were used in domestic rabbits, but trapping and vaccinating wild rabbits, which are notoriously fast-breeding, was an insurmountable task, Sánchez-Vizcaíno explains. He saw huge potential in self-spreading vaccines. In the laboratory, Sánchez-Vizcaíno, then the director of the Center for Research in Animal Health in Spain, and his team sliced out a gene from the rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus and inserted it into the genome of a mild strain of the myxoma virus, which causes myxomatosis. The final product was a hybrid virus vaccine that protected against both rabbit hemorrhagic disease and myxomatosis. Sánchez-Vizcaíno hypothesized that because the vaccine was similar enough to the original disease-causing myxoma virus, it would still spread among wild rabbits. On the island the research team captured 147 rabbits, placed microchips in their necks, administered the vaccine to about half of them, and released them all back into the wild. For the next 32 days, the vaccinated and unvaccinated rabbits lived as they normally did. When researchers recaptured micro-chipped rabbits that had not been vaccinated originally, they found that 56 percent of them had antibodies to both viruses, indicating that the vaccine had successfully spread from vaccinated to unvaccinated animals. The experiment was the first proof-of-concept field test for self-spreading vaccines—and it remains the only one ever attempted. In 2000, the research team submitted their laboratory and field data to the European Medicines Agency, or EMA, for evaluation and approval for real-world use. The EMA noted technical issues with the vaccine’s safety evaluation and requested that the team decode the myxoma genome, which had not been done before. Although the team was given two years to comply, the funding body did not provide support for further work, recalls Juan Bárcena, then a Ph.D. student working under Sánchez-Vizcaíno. Bárcena no longer advocates for self-spreading vaccine technology, but he says that data from the laboratory and field trials showed the vaccine was safe and its spread remained confined to the rabbit populations. Still, Bárcena doubts that the EMA would have ever approved their vaccine given the hesitancy and controversy around genetically modified organisms. Scott Nuismer, a professor at the University of Idaho who conducts mathematical modelling studies of self-spreading vaccines today, noted that Sánchez-Vizcaíno’s vaccine may have posed more risks than current technologies because the team used a myxoma virus, which is itself deadly, as its vehicle for the vaccine. After the Isla del Aire field trials, research into self-spreading vaccines went largely dormant. Pharmaceutical companies weren’t interested in investing in research and development for a technology that, by design, would reduce its own profit margins, Sánchez-Vizcaíno speculates.....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Clinical trial data find an Ebola vaccine regimen safe, well tolerated, and produces a strong immune response in people over the age of one. Welcome news for Ebola virus disease prevention was published yesterday in two papers presenting data showing that Johnson & Johnson’s (J&J) two-dose Ebola vaccine regimen is safe, well tolerated, and produces a strong immune response in people over the age of one. This news comes five years after the largest outbreak of Ebola since its discovery and just one month after an Ebola outbreak was declared in the Ivory Coast. The study aimed to assess the safety and long-term immunogenicity of a two-dose vaccine regimen. The first vaccine is the adenovirus type 26 vector-based vaccine encoding the Ebola virus glycoprotein (Ad26.ZEBOV). The second is the modified vaccinia Ankara vector-based vaccine, encoding glycoproteins from Ebola virus, Sudan virus, and Marburg virus, and the nucleoprotein from the Tai Forest virus (MVA-BN-Filo). The authors found that the vaccine regimen was well tolerated and induced antibody responses to Zaire ebolavirus 21 days after the second dose in 98% of participants, with the immune responses persisting in adults for at least two years. Conducted in Sierra Leone, the EBOVAC-Salone study is the first to assess the safety and tolerability of this vaccine regimen in a region affected by the 2014–2016 West African Ebola outbreak, which was the worst on record. It is also the first study reporting the evaluation of this vaccine regimen in children. The data were published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases in two separate papers: “Safety and immunogenicity of the two-dose heterologous Ad26.ZEBOV and MVA-BN-Filo Ebola vaccine regimen in children in Sierra Leone: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial” and “Safety and long-term immunogenicity of the two-dose heterologous Ad26.ZEBOV and MVA-BN-Filo Ebola vaccine regimen in adults in Sierra Leone: a combined open-label, non-randomized stage 1, and a randomized, double-blind, controlled stage 2 trial.” During the 2014–16 outbreak of Ebola in West Africa, 28,652 cases and 11,325 deaths from Ebola were reported. Approximately 20% of cases were in children under 15 years, and children younger than five years are at a higher risk of death than adults. “This study represents important progress in the development of an Ebola virus disease vaccine regimen for children, and contributes to the public health preparedness and response for Ebola outbreaks,” said Muhammed Afolabi, MD, assistant professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The clinical trial recruited participants from September 2015 to July 2018. The study was divided into two stages. In stage one, 43 adults aged 18 years or older received the Ad26.ZEBOV vaccine followed by the MVA-BN-Filo vaccine after 56 days. In stage two, 400 adults and 576 children and adolescents (192 in each of the three age cohorts of 1–3, 4–11 and 12–17 years of age) were vaccinated with either the Ebola vaccine regimen (Ad26.ZEBOV followed by MVA-BN-Filo) or a single dose of a meningococcal quadrivalent conjugate vaccine followed by placebo on day 57. Adults participating in stage one of the study were offered a booster dose of A26.ZEBOV two years after the first dose which induced a strong immune response within seven days. “To protect people from Ebola, we will need a range of effective interventions,” said Daniela Manno, clinical assistant professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “These findings support the additional strategy of providing an Ad26.ZEBOV booster to previously immunized individuals at the start of an Ebola virus disease outbreak.” The study findings have already contributed to the approval and marketing authorization of the two-dose Ebola vaccine regimen in July 2020 by the European Medicines Agency, for use in both children and adults. It also contributed to the WHO Prequalification in April 2021, which will facilitate formal registrations of this vaccine regimen in countries at risk of Ebola virus disease outbreaks. “The threat of future Ebola virus disease outbreaks is real and it’s important to remember that this disease has definitely not gone away,” noted Deborah Watson-Jones, PhD, clinical epidemiologist from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. “Despite the additional global challenges around COVID-19, we must not slow down efforts to find effective ways of preventing Ebola virus epidemics and, should outbreaks occur, of containing them rapidly. Vaccines have a key role in meeting both of these objectives.” In May 2021, J&J said it would donate thousands of Ebola vaccine regimens in support of a WHO early access clinical program launched in response to an outbreak in Guinea and aimed at preventing Ebola in West Africa. The program began by vaccinating health workers, other frontline workers and others at increased risk of exposure to the Ebola virus in Sierra Leone. To date, more than 250,000 individuals participating in clinical trials and vaccination initiatives have received at least the first dose of the J&J Ebola vaccine regimen, including 200,000 who have been fully vaccinated. Further studies are being carried out in Sierra Leone to investigate whether the vaccines are safe and induce immune responses among infants aged under one year, and to follow up the adult and child participants over five years to assess the potential for long term protection. “This is an example of crucial research which brings together scientists from Africa with partners in the north and pharmaceutical companies to tackle a major public heath threat in Africa,” said Sir Brian Greenwood, MD, professor of clinical tropical medicine, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The research in Kambia district was a collaboration between the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Sierra Leone’s College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences under the EBOVAC1 project. See research published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases (Sept.13, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00128-6 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00125-0

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

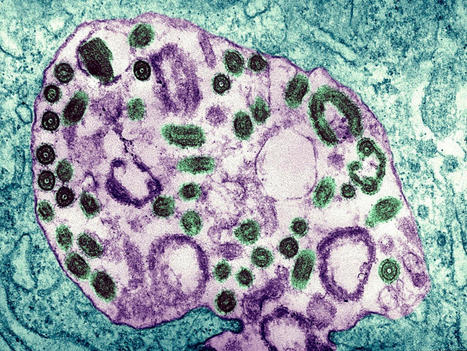

The Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) is a rare and deadly disease in people and nonhuman primates. The viruses that cause EVD are located mainly in sub-Saharan Africa. People can get EVD through direct contact with an infected animal (bat or nonhuman primate) or a sick or dead person infected with Ebola virus. The virus is extremely skilled at escaping the immune system’s defenses. However, new hope comes from a study by Mount Sinai researchers, who report they have uncovered the complex cellular mechanisms of Ebola virus. Their research may help to identify potential pathways to treatment and prevention. The findings are published in the journal mBio, “Expression of the Ebola Virus VP24 Protein Compromises the Integrity of the Nuclear Envelope and Induces a Laminopathy-Like Cellular Phenotype.” “Ebola virus (EBOV) VP24 protein is a nucleocapsid-associated protein that inhibits interferon (IFN) gene expression and counteracts the IFN-mediated antiviral response, preventing nuclear import of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1),” wrote the researchers. “Proteomic studies to identify additional EBOV VP24 partners have pointed to the nuclear membrane component emerin as a potential element of the VP24 cellular interactome. Here, we have further studied this interaction and its impact on cell biology. We demonstrate that VP24 interacts with emerin but also with other components of the inner nuclear membrane, such as lamin A/C and lamin B.” The team reported “how a protein of the Ebola virus, VP24, interacts with the double-layered membrane of the cell nucleus (known as the nuclear envelope), leading to significant damage to cells along with virus replication and the propagation of disease.” “The Ebola virus is extremely skilled at dodging the body’s immune defenses, and in our study we characterize an important way in which that evasion occurs through disruption of the nuclear envelope, mediated by the VP24 protein,” said co-senior author Adolfo García-Sastre, PhD, professor of microbiology, and director of the Global Health and Emerging Pathogens Institute of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “That disruption is quite dramatic and replicates rare, genetic diseases known as laminopathies, which can result in severe muscular, cardiovascular, and neuronal complications.” The researchers collaborated with research partners from CIMUS at the Universidad de Santiago de Compostela in Spain, and the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, Germany. Together, they identified the cellular membrane components that interact with VP24 to prompt nuclear membrane disruption. The researchers demonstrated that VP24 disrupts signaling pathways that are meant to activate the immune system’s defenses against viruses. “We believe our discovery of the novel activities of the Ebola VP24 protein and the severe damage it causes to infected cells will help to promote further research into effective ways to treat and prevent the spread of deadly viruses, perhaps through a new inhibitor,” added García-Sastre. “Indeed, that research will hopefully identify even more precisely the molecular mechanisms by which viruses like Ebola invade the body and find ways to cleverly avoid its immune defenses.” Published in mBio (July 6, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00972-21

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Today marks the end of the 12th Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, just three months after the first case was reported in North Kivu. The Ebola outbreak that re-emerged in February came nine months after another outbreak in the same province was declared over. The World Health Organization (WHO) congratulates the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s health authorities and the heath workers on the ground for their swift response which built on the country’s previous experience in tackling Ebola outbreaks. This outbreak is the country’s fourth in less than three years. Eleven confirmed cases and one probable case, six deaths and six recoveries were recorded in four health zones in North Kivu since 7 February when the Ministry of Health announced the resurgence of Ebola in Butembo, a city in North Kivu Province and one of the hotspots of the 2018–2020 outbreak. Results from genome sequencing conducted by the country’s National Institute of Biomedical Research found that the first Ebola case detected in the outbreak was linked to the previous outbreak, but the source of infection is yet to be determined. “Huge credit must be given to the local health workers and the national authorities for their prompt response, tenacity, experience and hard work that brought this outbreak under control,” said Dr Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Direct for Africa. “Although the outbreak has ended, we must stay alert for possible resurgence and at the same time use the growing expertise on emergency response to address other health threats the country faces.” The response was coordinated by the Provincial Department of Health in collaboration with WHO and partners. WHO had nearly 60 experts on the ground and as soon as the outbreak was declared helped local workers to trace contacts, provide treatment, engage communities and vaccinate nearly 2000 people at high risk, including over 500 frontline workers. The response was often hampered by insecurity caused by armed groups and social disturbances which at times limited the movement of responders. The area where the outbreak took place is one where the population is highly mobile as people move to conduct business or visit family and friends. Butembo city is about 150 km from the Uganda border and there were concerns over the potential cross-border spread of the outbreak. However, due to the effective response the outbreak stayed limited to North Kivu province. While the 12th outbreak is over, there is a need for continued vigilance and maintaining a strong surveillance system as potential flare-ups are possible in the months to come. It is important to continue with sustained disease surveillance, monitoring of alerts and working with communities to detect and respond rapidly to any new cases and WHO will continue to assist health authorities with their efforts to contain quickly a sudden re-emergence of Ebola. WHO continues to work with the Democratic Republic of the Congo to fight other public health problems such as outbreaks of measles and cholera, the COVID-19 pandemic and a weak health system. The 2018–2020 outbreak was the 10th in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the country’s deadliest, with 3481 cases, 2299 deaths and 1162 survivors. The country also experienced its 11th outbreak which took place in Equateur Province last year. Currently there is an ongoing Ebola outbreak in Guinea, which began in February of this year.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Genome analyses suggesting virus persistence raise worries about stigmatization of survivors. An Ebola outbreak in Guinea that has so far sickened at least 18 people and killed nine has stirred difficult memories of the devastating epidemic that struck the West African country between 2013 and 2016, along with neighboring Liberia and Sierra Leone, leaving more than 11,000 people dead. But it may not just be the trauma that has persisted. The virus causing the new outbreak barely differs from the strain seen 5 to 6 years ago, genomic analyses by three independent research groups have shown, suggesting the virus lay dormant in a survivor of the epidemic all that time. “This is pretty shocking,” says virologist Angela Rasmussen of Georgetown University. “Ebolaviruses aren’t herpesviruses”—which are known to cause long-lasting infections—“and generally RNA viruses don’t just hang around not replicating at all.” Scientists knew the Ebola virus can persist for a long time in the human body; a resurgence in Guinea in 2016 originated from a survivor who shed the virus in his semen more than 500 days after his infection and infected a partner through sexual intercourse. “But to have a new outbreak start from latent infection 5 years after the end of an epidemic is scary and new,” says Eric Delaporte, an infectious disease physician at the University of Montpellier who has studied Ebola survivors and is a member of one of the three teams. Outbreaks ignited by Ebola survivors are still very rare, Delaporte says, but the finding raises tricky questions about how to prevent them without further stigmatizing Ebola survivors. The current outbreak in Guinea was detected after a 51-year-old nurse who had originally been diagnosed with typhoid and malaria died in late January. Several people who attended her funeral fell ill, including members of her family and a traditional healer who had treated her, and four of them died. Researchers suspected Ebola might have caused all of the deaths, and in early February they discovered the virus in the blood of the nurse’s husband. An Ebola outbreak was officially declared on 13 February, with the nurse the likely index case. The Guinea Center for Research and Training in Infectious Diseases (CERFIG) and the country’s National Hemorrhagic Fever Laboratory have each read viral genomes from four patients; researchers at the Pasteur Institute in Dakar, Senegal, sequenced two genomes. In three postings today on the website virological.org, the groups agree the outbreak was caused by the Makona strain of a species called Zaire ebolavirus, just like the past epidemic. A phylogenetic tree shows the new virus falls between virus samples from the 2013–16 epidemic. Until recently, scientists assumed Ebola epidemics start when a virus jumps species, from an animal host to humans. Theoretically, that could have happened in Guinea, says virologist Stephan Günther of the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, who worked with one of the three teams. But given the similarity between viruses from the epidemic and the new ones, “It must be incredibly unlikely.” Outside scientists agree but say it hasn’t been proved that Ebola lay dormant in one person for 5 years. “From the tree, you’d conclude that it is a virus that persisted in some way in the area, and sure, most likely in a survivor,” says Dan Bausch, a veteran of several Ebola outbreaks who leads the United Kingdom’s Public Health Rapid Support Team. But it is hard to rule out scenarios such as a small, unrecognized chain of human to human transmission, Bausch adds: “For example, a 2014 survivor infects his wife a few years after recovery, who infects another male, who survives and carries virus for a few years, then infecting another women, who is then seen by a nurse who dies”—the index case in the new outbreak. The nurse was not known to be a survivor herself, but she could have had contact with a survivor privately or through her job, or she might have been infected herself years ago with few symptoms. “Figuring out what exactly happened is one of the biggest questions now,” Bausch says. Another ongoing outbreak of Ebola in North Kivu, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was also started by transmission from someone infected during a previous outbreak, Delaporte notes. (The survivor had tested negative for Ebola twice after his illness in 2020.) Taken together, that suggests humans are now as likely to be the source of a new outbreak of Ebola as wildlife, he says. “This is clearly a new paradigm for how these outbreaks start.” Outbreaks sparked by survivors may even become more likely, now that increasing mobility and other factors have caused each eruption of Ebola to become bigger, resulting in more survivors, says Fabian Leendertz, a wildlife veterinarian who was involved in the sequencing. The cases raise important new research questions, Bausch says: “How do we need to change our response to escape from the cycle of outbreak-response-reintroduction-outbreak?” he asks. “Can we use new therapeutics to clear virus from survivors?” But the most immediate question is what these results mean for Ebola survivors, who face a lot of hardship already. Many have not only lost friends and family to the virus, but also struggle with long-term aftereffects, such as muscle pains and eye problems. In a study published in February, Delaporte found that about half of more than 800 Ebola survivors in Guinea still reported symptoms 2 years after their illness, and one-quarter after 4 years. On top of this, survivors have faced intense stigmatization. Many conspiracy theories swirled in the aftermath of the epidemic, including the claim that survivors had sold family members to international organizations to save themselves, says Frederic Le Marcis, a social anthropologist at the École Normale Supérieure of Lyon and the French Research Institute for Development, who is working in Guinea. One man, he says, was the only one to survive out of 11 family members and when he came back, no one wanted to work with him. “He was seen as someone untrustworthy.” News that a survivor likely touched off the current outbreak could cause further problems for survivors, Le Marcis says: “Will they be highlighted as a source of danger? Will they be chased out of their own families and communities?” Alpha Keita, a virologist who led the sequencing work at CERFIG, worries about stigmatization and even violence against survivors have occupied him since he first got the surprising results a week ago. One important message to the public should be that some people infected with Ebola show few symptoms, meaning people may be survivors without knowing it. “So don’t stigmatize Ebola survivors—you don’t know that you are not a survivor yourself,” Keita says. Bausch calls for an educational campaign explaining that unprotected sex with an Ebola survivor may pose a risk, but casual contacts such as shaking hands and working together do not. And although there needs to be some medical monitoring of survivors, it cannot just be about testing them for Ebola virus, he says. “We need to recognize and assist with all the other challenges, physical, mental, and social, that survivors and their families face.” The key, Bausch says, is to “not just treat survivors as some hot potato risk of starting another outbreak.” It also presents a challenge to the country’s health care system if every patient with fever and diarrhea has to be a considered potential Ebola case, Le Marcis says. Fortunately, Ebola vaccines and treatments have become available in recent years. Already, several thousand contacts of the new Ebola patients, and contacts of these contacts, have been vaccinated. Health care workers are being immunized as well. Vaccinating survivors might even help clear latent infections, Rasmussen says. And the fact that viral samples were sequenced in Guinea this time around shows the country’s scientific capabilities have improved, Delaporte says: “Seven years ago, when the epidemic started, there was no infrastructure in Guinea to be able to do this.” Sequences of the EBOV strain available in Virological (March 12, 2021): https://virological.org/t/guinea-2021-ebov-genomes/651

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The wife of a survivor of a large Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has died from the disease nearly 8 months after the outbreak was declared over, WHO said, raising concerns about a resurgence of the virus.According to WHO, the DRC Ministry of Health reported the new case in Butembo, a city in North Kivu, the eastern province where the 2018-2020 outbreak took place. The woman, whose samples tested positive for Ebola, sought medical attention for Ebola-like symptoms and later died. So far, more than 70 contacts have been identified, WHO said. “The expertise and capacity of local health teams has been critical in detecting this new Ebola case and paving the way for a timely response,” WHO Regional Director for Africa Matshidiso Moeti, MBBS, MSc, said in a press release. “WHO is providing support to local and national health authorities to quickly trace, identify and treat the contacts to curtail the further spread of the virus.” The North Kivu outbreak lasted nearly 2 years and was declared over in June 2020. There were 3,481 cases and 2,299 deaths attributed to the outbreak, and more than 1,160 people recovered. It was the second largest Ebola outbreak on record after the West African epidemic, which lasted from 2014-2016 and killed more than 11,000 people. WHO reported that genome sequencing is currently underway to identify the strain of Ebola the woman had and to determine if it is linked to the previous outbreak. It is unclear if the woman had been vaccinated against Ebola or how she was infected. WHO warned last year that the region could see flare-ups of Ebola, which occurred frequently following the West African epidemic. Ebola survivors who no longer have symptoms can still carry the virus — in semen, for example — allowing for its reintroduction.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The disease killed at least 55 people in an outbreak that began June 1, the 11th bout of Ebola to strike the Democratic Republic of Congo. KINSHASA, Democratic Republic of Congo — The government on Wednesday declared the end of the latest Ebola epidemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo, closing the file on an outbreak in the northwestern province of Equateur that killed dozens over six months. “I am happy to solemnly declare the end of the 11th epidemic of the Ebola virus,” Health Minister Eteni Longondo told journalists. The World Health Organization said the latest outbreak had killed 55 people among 119 confirmed and 11 probable cases since June 1. Dr. Longondo’s announcement came after the Democratic Republic of Congo crossed a threshold of 42 days without a recorded case — double the period that the deadly virus takes to incubate. As during a preceding epidemic in the east of the country, the widespread use of vaccinations, which were administered to more than 40,000 people, helped curb the disease, the W.H.O. said. The outbreak in Equateur began as health workers were still battling an Ebola epidemic in the east and amid tough measures, since eased, to combat the coronavirus. Despite the official end of the Equateur outbreak, Dr. Longondo expressed caution. “There remains a high risk of a resurgence, and this should be an alarm signal for strengthening the monitoring system,” the minister said. The eastern outbreak, which ran from Aug. 1, 2018 to June 25 of this year, was the country’s worst ever, with 2,277 deaths. It was also the second highest toll in the 44-year history of the disease, surpassed only by a three-country outbreak in West Africa from 2013 to 2016 that killed 11,300 people. The Ebola virus spreads via contact with the blood, body fluids, secretions or organs of an infected or recently deceased person. The early symptoms are high fever, weakness, intense muscle and joint pain, headaches and sore throats, followed by internal and external bleeding and organ failure. The death rate ranges as high as 90 percent in some outbreaks, according to the W.H.O.

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A drug studied for cancer, COVID-19 and radiation injuries appears to be effective against Ebola in mice. | From cancer to COVID-19 to radiation injuries, and now Ebola: RedHill Bio reports that its drug opaganib appears to be effective against the virus in mice. RedHill Biopharma, in collaboration with the U.S. Army, announced Oct. 3 that twice-daily oral doses of the medication opaganib boosted survival from about six days in controls to 11 days in animals infected with the virus. In the group treated with the highest dose, 30% of the mice survived, compared to none of the controls. “Given the unmet medical need … these results with opaganib, an easy to distribute and administer oral small molecule drug, support its further investigation for use in treating Ebola,” study lead Rekha Panchal, Ph.D., principal investigator of therapeutics discovery at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, said in a press release. Opaganib is a host-directed antiviral, meaning it prevents a virus from hijacking a host’s cells for replication rather than destroying the pathogen directly. The drug mainly works by inhibiting the enzyme sphingosine kinase-2, or SPHK2, a key enzyme in a process called sphingolipid metabolism. Inhibiting sphingolipid metabolism with opaganib turns on processes that clear or repair infected cells, like autophagy and apoptosis. That mechanism has prompted studies on opaganib in a range of indications from cancer to COVID. Under the name Yeliva, the drug received orphan-drug designation from the FDA in 2017 for the treatment of bile duct cancer and has been tested for that indication through phase 2a. It’s also in a phase 2 study for prostate cancer. In 2021, the drug flopped in a phase 2/3 test on patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia, though RedHill said at the time it would continue investigating the drug in patients who were earlier in the course of their disease. In February 2023, opaganib was selected for investigation by the National Institutes of Health and the Radiation and Nuclear Countermeasures Program as a potential treatment for acute radiation syndrome. The move came on the back of preclinical studies in mice suggesting it could prevent damage from ionizing radiation. If the drug were to show efficacy against Ebola in humans, it would be only the third to do so. The two FDA-approved treatments for the virus both rely on antibodies that prevent it from entering the host’s cells and must be given by IV. Red Hill Biopharma Press Release (Oct. 3, 2023): https://www.redhillbio.com/news/news-details/2023/RedHill-and-U.S.-Army-Announce-Opaganibs-Ebola-Virus-Disease-Survival-Benefit-in-U.S.-Army-Funded-In-Vivo-Study/default.aspx

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

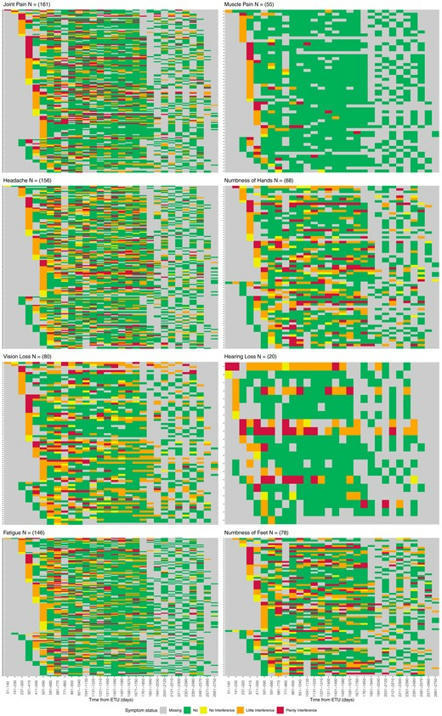

Background Lingering symptoms have been reported by survivors of Ebola virus disease (EVD). There are few data describing the persistence and severity of these symptoms over time. Methods Symptoms of headache, fatigue, joint pain, muscle pain, hearing loss, visual loss, numbness of hands or feet were longitudinally assessed among participants in the Liberian Ebola Survivors Cohort study. Generalized linear mixed effects models, adjusted for sex and age, were used to calculate the odds of reporting a symptom and it being rated as highly interfering with life. Results From June 2015 to June 2016, 326 survivors were enrolled a median of 389 days (range 51–614) from acute EVD. At baseline 75.2% reported at least 1 symptom; 85.8% were highly interfering with life. Over a median follow-up of 5.9 years, reporting of any symptom declined (odds ratio for each 90 days of follow-up = 0.96, 95% confidence interval [CI]: .95, .97; P < .0001) with all symptoms declining except for numbness of hands or feet. Rating of any symptom as highly interfering decreased over time. Among 311 with 5 years of follow-up, 52% (n = 161) reported a symptom and 29% (n = 47) of these as highly interfering with their lives. Conclusions Major post-EVD symptoms are common early during convalescence and decline over time along with severity. However, even 5 years after acute infection, a majority continue to have symptoms and, for many, these continue to greatly impact their lives. These findings call for investigations to identify the mechanisms of post-EVD sequelae and therapeutic interventions to benefit the thousands of effected EVD survivors. Published in Clinical Infectious Diseases (Sept. 2022):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Equatorial Guinea has just confirmed its first outbreak of deadly Marburg virus, a hemorrhagic fever related to Ebola. Equatorial Guinea has just confirmed its first outbreak of Marburg virus, one of the families of hemorrhagic fevers related to Ebola. As with last year’s outbreak in Ghana, patient specimens had to be sent to the Institut Pasteur in Senegal for confirmation, as it requires specialized testing. One of eight samples has been confirmed thus far. There have been 16 suspected cases and 9 deaths so far. Symptoms of Marburg are nonspecific and include (the often abrupt onset of) fever, headache, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, so it might be confused with many other infections. When there is blood in the emesis or stool, the diagnosis of a hemorrhagic fever becomes much clearer. The incubation period is from 2-21 days. Like Ebola, Marburg can be quite deadly, with an 88% fatality rate. Unlike Ebola, we have no vaccines to protect people yet, or other specific treatments. Monoclonal antibodies have been used to successfully treat some people ill with Ebola, with a moderate reduction in death, from 49.4% to 35.1% for Ebanga (Ansuvimab-zykl) treatment. The vaccine for Ebola offered a 97.5% protection rate in the 2018-20 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which was due to the Ebola Zaire strain. The most recent outbreak of Ebola in Africa occurred in Uganda in September 2022. It was due to a different strain, Ebola Sudan, for which we have no vaccines or specific treatment. For Marburg, Ebola Sudan, and other hemorrhagic fevers, treatment is supportive by providing fluids and electrolytes to avoid shock. The primary focus now will be controlling the spread of the infection, which occurs through these infected secretions or contaminated surfaces, and by quarantine. Patients who are symptomatic need to be carefully isolated. The WHO and local officials will provide education on infection control and supplies of gowns and gloves (PPE). Contact with bodies is common in many cultures and has previously been a source of transmission. Marburg has now been seen in Ghana, Angola, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, and South Africa. The first outbreak was seen in 1967 in Germany and Serbia. It came from the importation of green monkeys from Angola. A quarter of the 31 people infected died. Subsequently, there were larger outbreaks in the DRC in 1998-2000, with 152 people and 83% mortality. The largest outbreak was in 2005 in Angola. There were 252 cases and a 90% death rate. This was thought to be caused by reusing contaminated transfusion equipment between patients. Egyptian Rousette bats, which live in caves and mines, are reservoirs for the Marburg virus. There have been infections among Uganda miners in 2007 from the Python Cave in Uganda. Subsequently, two tourists became infected from the same site, where they had gone caving. Bat guano or infected aerosols were the likely sources of transmission. One of the problems with Marburg, as with other animal-related infections (zoonosis), is that there is limited surveillance and diagnostic tests; until there is an outbreak, early cases are likely to be missed. Many of these events—called spillover events—occur because we encroach on wildlife. As we do this more—be it in mining, deforestation for cattle, or other disruptions of the environment, we can expect to see more such outbreaks.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Lloviu cuevavirus (LLOV) was the first identified member of Filoviridae family outside the Ebola and Marburgvirus genera. A massive die-off of Schreibers’ bent-winged bats (Miniopterus schreibersii) in the Iberian Peninsula in 2002 led to its discovery. Studies with recombinant and wild-type LLOV isolates confirmed the susceptibility of human-derived cell lines and primary human macrophages to LLOV infection in vitro. Based on these data, LLOV is now considered as a potential zoonotic virus with unknown pathogenicity to humans and bats. We examined bat samples from Italy for the presence of LLOV in an area outside of the currently known distribution range of the virus. We detected one positive sample from 2020, sequenced the complete coding sequence of the viral genome and established an infectious isolate of the virus. In addition, we performed the first comprehensive evolutionary analysis of the virus, using the Spanish, Hungarian and the Italian sequences. The most important achievement of this article is the establishment of an additional infectious LLOV isolate from a bat sample using the SuBK12-08 cells, demonstrating that this cell line is highly susceptible to LLOV infection. These results further confirms the role of these bats as the host of this virus, possibly throughout their entire geographic range. This is an important result to further understand the role of bats as the natural hosts for zoonotic filoviruses. Preprint available at bioRxiv (Dec. 5, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.05.519067

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Most RNA viruses cause acute infections that are cleared from the host as they lack the mechanisms to persist; however, phenomena such as "long COVID" suggest that viral RNA can persist after clinical recovery and elimination of detectable infectious virus. This Unsolved Mystery article explores the meaning, origins and consequences of such persistent RNA. DNA viruses often persist in the body of their host, becoming latent and recurring many months or years later. By contrast, most RNA viruses cause acute infections that are cleared from the host as they lack the mechanisms to persist. However, it is becoming clear that viral RNA can persist after clinical recovery and elimination of detectable infectious virus. This persistence can either be asymptomatic or associated with late progressive disease or nonspecific lingering symptoms, such as may be the case following infection with Ebola or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Why does viral RNA sometimes persist after recovery from an acute infection? Where does the RNA come from? And what are the consequences? PLOS Biology (June 2022): https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001687

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

In past Ebola outbreaks, fatality rates have varied from 25% to 90% - but effective treatments are now available, and patients who receive care early see their chances of survival improve significantly. An outbreak of Ebola has been declared in the Democratic Republic of the Congo - four months after the last one ended. A case was confirmed in a 31-year-old man on 5 April. He was admitted to an Ebola treatment centre on Thursday, but died hours later. The World Health Organisation's regional director for Africa, Dr Matshidiso Moeti, said: "Time is not on our side. The disease has had a two-week head start and we are now playing catch-up." Overall, this is the 14th Ebola outbreak that the Democratic Republic of the Congo has seen since 1976, which is when the virus was first discovered. Efforts to stem the current outbreak have already begun, with officials confirming that the patient who died has received a safe and dignified burial. More than 70 of his contacts are also being traced - and vaccinations in the city of Mbandaka are going to be stepped up. Ebola is transmitted by coming into contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person or contaminated materials. Early symptoms include muscle aches and a fever, which resemble those seen in other common diseases such as malaria. In past Ebola outbreaks, fatality rates have varied from 25% to 90% - but effective treatments are now available, and patients who receive care early see their chances of survival improve significantly. Dr Moeti added: "The positive news is that health authorities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo have more experience than anyone else in the world at controlling Ebola outbreaks quickly."

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A core question in understanding the drivers of zoonotic emergence is whether particular animal groups are common sources of zoonotic viruses. If so, can this information be used to establish a watch-and-act list of those species most likely to carry potentially pandemic viruses? It has long been known that most viral infections in humans have their ancestry in mammals (4). Birds are the only other probable source of zoonotic diseases, with the various forms of avian influenza virus that occasionally appear in humans (such as H5 subtype viruses) presenting an ongoing pandemic threat. Although viruses are often abundant in other animal groups (such as bony fish), their phylogenetic distance to humans greatly reduces the likelihood of successful cross-species transmission. Within the mammals, a variety of groups have served as reservoirs for zoonotic viruses (3), particularly those with which humans share proximity, either as food sources (such as pigs) or because they have adapted to human lifestyles (like some species of rodent), as well as those that are so closely related to humans (such as nonhuman primates) that viruses face little adaptive challenge when establishing human-to-human transmission. Most of all, since the emergence of SARS in late 2002, there has been intense interest in bats as virus reservoirs, although this may in part reflect biases in both ascertainment and confirmation (5). Although bats seemingly tolerate a high diversity and abundance of viruses, the underlying immunological, physiological, and ecological reasons for this are not fully understood (6). More pragmatically, the majority of bat viruses have not appeared in humans, and those that have emerged often do so through other host species (i.e., “intermediate hosts”) prior to successful emergence (7). Bats are important players in disease emergence, but they are only one component of the more complex global viral ecosystem. A related question is whether the viruses that are most likely to emerge in humans can be identified. Although metagenomic sequencing is revealing an increasingly large virosphere, with mammals carrying many thousands of different viruses, most of which remain undocumented (5), the greatest pandemic risk is posed by respiratory viruses because their fluid mode of (sometimes asymptomatic) transmission makes their control especially challenging. Three groups of RNA viruses that regularly jump species boundaries best fit this risk profile: paramyxoviruses, influenza viruses, and, particularly, coronaviruses. Hendra and Nipah viruses, both with ultimate bat ancestry, are exemplars of paramyxoviruses that have emerged in humans. Although neither have resulted in large-scale outbreaks, it is possible that more transmissible paramyxoviruses (such as the case of measles virus) lurk in the mammalian virosphere. The documented host range of influenza viruses is growing, including recent reports of avian H9N2 influenza virus in diseased Asian badgers (2), but most human influenza virus pandemics have their roots in those viruses that circulate in waterbirds and poultry, often with the secondary involvement of pigs. Fortunately, birds and humans are sufficiently different in most virus–cell interactions that avian viruses are usually unable to successfully transmit among humans......

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A patient with the rare, but highly infectious Marburg virus disease has died in Guinea, according to a World Health Organization (WHO) statement on Monday. It's the first case of the Ebola-like virus in West Africa. Samples of the virus, which causes hemorrhagic fever, were taken from the patient in Gueckedou. The statement added that the detection comes less than two months after Guinea declared an end to its most recent Ebola outbreak. "Gueckedou, where Marburg has been confirmed, is also the same region where cases of the 2021 Ebola outbreak in Guinea as well as the 2014--2016 West Africa outbreak were initially detected," according to the WHO statement. "Samples taken from a now-deceased patient and tested by a field laboratory in Gueckedou as well as Guinea's national haemorrhagic fever laboratory turned out positive for the Marburg virus. Further analysis by the Institut Pasteur in Senegal confirmed the result." Health authorities on Monday were attempting to find people who may have had contact with the patient as well as launching a public education campaign to help curb the spread of infection. An initial team of 10 WHO experts are on the ground to probe the case and support Guinea's emergency response. "We applaud the alertness and the quick investigative action by Guinea's health workers. The potential for the Marburg virus to spread far and wide means we need to stop it in its tracks," Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, WHO regional director for Africa, said in the statement. According to WHO, the virus is transmitted to humans from fruit bats and can then be spread human-to-human through direct contact with the bodily fluids of infected people or surfaces and materials contaminated with these fluids. There are no vaccines or antiviral treatments to treat Marburg; however, there are treatments for specific symptoms that can improve patients' chances for survival. "Case fatality rates have varied from 24% to 88% in past outbreaks depending on virus strain and case management," the statement said. "In Africa, previous outbreaks and sporadic cases have been reported in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, South Africa and Uganda." Marburg virus was first identified in 1967, when 31 people became sick in Germany and Yugoslavia in an outbreak that was eventually traced back to laboratory monkeys imported from Uganda. Since then the virus has appeared sporadically, with just a dozen outbreaks on record. Many of those involved only one diagnosed case. Marburg virus causes symptoms similar to Ebola, beginning with fever and weakness and often leading to internal or external bleeding, organ failure and death. Samson Ntale contributed to this report.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Long before COVID-19, scientists had been working to identify animal viruses that could potentially jump to people. These efforts have led to a Web-based platform called SpillOver, which ranks the risk that various viruses will make the leap. Developers hope the new tool will help public health experts and policymakers avoid future outbreaks. Jonna Mazet, an epidemiologist and disease ecologist at the University of California, Davis, has led this work for more than a decade. It began with the USAID PREDICT project, which sought to go beyond well-tracked influenza viruses and identify other emerging pathogens that pose a risk to humans. Thousands of scientists scoured more than 30 countries to locate and identify animal viruses, discovering many new ones in the process. But not every virus is equally threatening. So Mazet and her colleagues decided to create a framework to interpret their findings. “We wanted to move beyond scientific stamp collecting [simply finding viruses] to actual risk evaluation and reduction,” she says. The team was surprised to find very little existing research on categorizing threats from viruses that are currently found only in animals but are in viral families that can likely cause disease in people. So the researchers started from scratch, identifying 31 factors pertaining to animal viruses (such as how they are transmitted), to their hosts (such as how many and varied they are), and to the environment (human population density, frequency of interaction with hosts, and more). These are summed up in a risk score out of 155; the higher the score, the more likelihood of spillover. Cornell University virologist Colin Parrish, who was not involved in the study, says the factors examined were important in previous spillovers. But he notes that other viruses' crossover risk may be heightened by unforeseeable factors that crop up later. “It's a bit like the stock market,” he says. The new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, ranks 887 animal-borne viruses. Twelve known human pathogens scored at the top—with the virus that causes COVID-19 in second place, just under the rat-carried Lassa virus. (Influenza would have topped the list if included, Mazet says, but flu variants are already tracked elsewhere.) Parrish notes that the list also omits insect-borne viruses and those from domesticated animals. “This is a work in progress,” he says. “I'm sure it will be iterated into a more powerful tool as more information and data become available. SpillOver is publicly editable, and scientists around the world are already contributing their own findings. Mazet hopes it catches the attention of public health practitioners and leaders, too. With targeted action, Mazet says, “we can ensure that we don't have these spillovers at all. Or if we do, we're ready for them—because we're watching.” See also research published in P.N.A.S. (April 13, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002324118

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

During the 2018–2020 Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in North Kivu province in the Democratic Republic of Congo, EVD was diagnosed in a patient who had received the recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus–based vaccine expressing a ZEBOV glycoprotein (rVSV-ZEBOV) (Merck). His treatment included an Ebola virus (EBOV)–specific monoclonal antibody (mAb114), and he recovered within 14 days. However, 6 months later, he presented again with severe EVD-like illness and EBOV viremia, and he died. We initiated epidemiologic and genomic investigations that showed that the patient had had a relapse of acute EVD that led to a transmission chain resulting in 91 cases across six health zones over 4 months. Published in NEJM (April 1, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2024670

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Guinea declared a new Ebola outbreak on Sunday when tests came back positive for the virus after three people died and four fell ill in the southeast - the first resurgence of the disease there since the world's worst outbreak in 2013-2016. The patients fell ill with diarrhoea, vomiting and bleeding after attending a burial in Goueke sub-prefecture. Those still alive have been isolated in treatment centres, the health ministry said. “Faced with this situation and in accordance with international health regulations, the Guinean government declares an Ebola epidemic,” the ministry said in a statement. The person buried on Feb. 1 was a nurse at a local health centre and died after being transferred for treatment to Nzerekore, a city near the border with Liberia and Ivory Coast. The 2013-2016 outbreak of Ebola in West Africa started in Nzerekore, the proximity of which to busy borders hampered efforts to contain the virus. It went on to kill at least 11,300 people, with the vast majority of cases in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Fighting Ebola again will place additional strain on health services in Guinea as they also battle the COVID-19 pandemic. Guinea, a country of about 12 million people, has so far recorded 14,895 coronavirus infections and 84 deaths. The Ebola virus causes severe vomiting and diarrhoea and is spread through contact with body fluids. It has a much higher death rate than COVID-19, but unlike the coronavirus it is not transmitted by asymptomatic carriers. The ministry said health workers are trying to trace and isolate the contacts of the Ebola cases and will open a treatment centre in Goueke, which is less than an hour’s drive from Nzerekore. The authorities have also asked the World Health Organization (WHO) for Ebola vaccines, it said. The new vaccines have greatly improved survival rates in recent years. “It’s a huge concern to see the resurgence of Ebola in Guinea, a country that has already suffered so much from the disease,” the WHO’s Regional Director for Africa, Matshidiso Moeti, was quoted as saying in a statement. Given how close the new outbreak is to the border, the WHO is working with health authorities in Liberia and Sierra Leone to beef up surveillance and testing capacities, the statement said. The vaccines and improved treatments helped efforts to end the second-largest Ebola outbreak on record, which was declared over in Democratic Republic of Congo last June after nearly two years and more than 2,200 deaths. But on Sunday, DRC reported a fourth new case of Ebola in North Kivu province, where a resurgence of the virus was announced on Feb. 7.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|