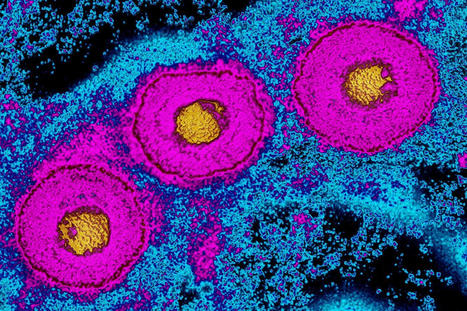

A genetically edited form of a herpes simplex virus—rewired to keep it from taking refuge in the nervous system and eluding an immune response—has outperformed a leading vaccine candidate in a new study from the University of Cincinnati, Northwestern University and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Published Nov. 6 in the journal Nature Vaccines, the study found that vaccinating guinea pigs with the modified live virus significantly increased the production of virus-combating antibodies. When challenged with a virulent strain of herpes simplex virus, the vaccinated animals displayed fewer genital lesions, less viral replication and less of the viral shedding that most readily spreads infection to others. The modified virus is actually a form of herpes simplex virus type 1, best known for causing cold sores around the lip. The fact that it demonstrated cross-protection against HSV type 2—the sexually transmitted type usually responsible for genital herpes—suggests that an HSV-2-specific edition of the vaccine could prove even more effective, the researchers said. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 500 million people have HSV-2, which persists for a lifetime and often flares up in response to stress. In addition to causing blisters, HSV-2 increases the risk for HIV infection and may contribute to Alzheimer's disease or other forms of dementia.

Despite the prevalence of the viruses, more than four decades of research have yet to yield an approved vaccine for HSV-1 or HSV-2. Part of the difficulty: The alphaherpesviruses, which include HSV, have evolved an especially sophisticated way of evading the immune responses aimed at destroying them. After infecting mucosal tissues of the mouth or genitourinary tract, HSV works its way to the tips of sensory nerves that transmit signals responsible for the sensations of pain, touch and the like. With the help of a specialized molecular switch, the virus then breaks into the nerve cell, hitching a ride on the molecular equivalent of a trolley car that transports it along a nerve fiber and into the nucleus of a sensory neuron. Whereas the mucosal infection is soon cleared by the immune response, the infected neurons become a sanctuary from the body's immune system, with HSV leaving only when stirred by rises in steroids or other stress-elevated hormones in the host. Nebraska's Gary Pickard and Patricia Sollars, alongside Northwestern's Gregory Smith and Tufts University's Ekaterina Heldwein, have spent years studying how to prevent HSV from reaching the safety of the nervous system. Heldwein advanced those efforts when she characterized the architecture of a certain alphaherpesvirus protein, pUL37, that the team suspected was integral to the virus moving along nerve fibers. Computer analyses based on that architecture suggested that three regions of the protein might prove important to the process.

Smith then carefully plucked out and replaced five codons, the fundamental coding information in the DNA, from the viral genome of each region. The researchers hoped that those mutations might help impede the virus from invading the nervous system. Their hopes were rewarded when Pickard and Sollars injected mice with a virus modified in region 2, or R2, of the protein. Rather than advancing deeper into the nervous system, the virus was stuck at the nerve terminal. But the team also knew that modifying HSV could have unintended consequences. "You can keep the virus from getting into the nervous system," said Pickard, professor of veterinary medicine and biomedical sciences at Nebraska. "That's not that hard to do by making broadly debilitating mutations. But when you knock down the virus so much that it doesn't replicate well, you are not rewarded with a robust immune response that can protect you from future exposures." So the researchers were heartened when further studies showed that the R2-mutated virus performed well as a vaccine in mice. Moreover, it circumvented certain stubborn issues that have cropped up with other vaccine approaches. Some approaches have involved challenging the immune system with only a subset of HSV components, or antigens, priming the body to recognize them but potentially miss others. Some have modified the virus so that it can replicate just once, preventing long-term persistence in the nervous system but also reducing spread in mucosal tissues and, by extension, a stout immune response....

Original study published in Nature Vaccines (Nov. 6, 2020):

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-020-00254-8

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...