Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Genetic analysis of 50,000-year-old Neanderthal skeletons has uncovered the remnants of three viruses related to modern human pathogens, and the researchers think they could be recreated. Genetic sequences from three common viruses that plague humanity today have been isolated from the remains of Neanderthals who lived more than 50,000 years ago. Marcelo Briones at the Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil, says it may be possible to synthesise these viruses and infect modern human cells with them in the lab... Preprint of the study in bioRxiv: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.16.532919

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

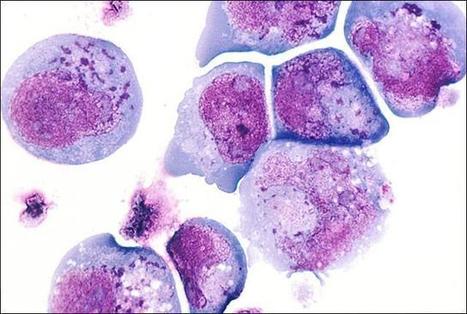

Little is known on the landscape of viruses that reside within our cells, nor on the interplay with the host imperative for their persistence. Yet, a lifetime of interactions conceivably have an imprint on our physiology and immune phenotype. In this work, we revealed the genetic make-up and unique composition of the known eukaryotic human DNA virome in nine organs (colon, liver, lung, heart, brain, kidney, skin, blood, hair) of 31 Finnish individuals. By integration of quantitative (qPCR) and qualitative (hybrid-capture sequencing) analysis, we identified the DNAs of 17 species, primarily herpes-, parvo-, papilloma- and anello-viruses (>80% prevalence), typically persisting in low copies (mean 540 copies/ million cells). We assembled in total 70 viral genomes (>90% breadth coverage), distinct in each of the individuals, and identified high sequence homology across the organs. Moreover, we detected variations in virome composition in two individuals with underlying malignant conditions. Our findings reveal unprecedented prevalences of viral DNAs in human organs and provide a fundamental ground for the investigation of disease correlates. Our results from post-mortem tissues call for investigation of the crosstalk between human DNA viruses, the host, and other microbes, as it predictably has a significant impact on our health. Published (April 24, 2023)in Nucleic Acids Research: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad199

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Ancient genomes from the herpes virus that commonly causes lip sores – and currently infects some 3.7 billion people globally – have been uncovered and sequenced for the first time by an international team of scientists led by the University of Cambridge. Latest research suggests that the HSV-1 virus strain behind facial herpes as we know it today arose around five thousand years ago, in the wake of vast Bronze Age migrations into Europe from the Steppe grasslands of Eurasia, and associated population booms that drove rates of transmission. Herpes has a history stretching back millions of years, and forms of the virus infect species from bats to coral. Despite its contemporary prevalence among humans, however, scientists say that ancient examples of HSV-1 were surprisingly hard to find. The authors of the study, published in the journal Science Advances, say the Neolithic flourishing of facial herpes detected in the ancient DNA may have coincided with the advent of a new cultural practice imported from the east: romantic and sexual kissing. “The world has watched COVID-19 mutate at a rapid rate over weeks and months. A virus like herpes evolves on a far grander timescale,” said co-senior author Dr Charlotte Houldcroft, from Cambridge’s Department of Genetics. “Facial herpes hides in its host for life and only transmits through oral contact, so mutations occur slowly over centuries and millennia. We need to do deep time investigations to understand how DNA viruses like this evolve,” she said. “Previously, genetic data for herpes only went back to 1925.” The team managed to hunt down herpes in the remains of four individuals stretching over a thousand-year period, and extract viral DNA from the roots of teeth. Herpes often flares up with mouth infections: at least two of the ancient cadavers had gum disease and a third smoked tobacco. The oldest sample came from an adult male excavated in Russia’s Ural Mountain region, dating from the late Iron Age around 1,500 years ago. Two further samples were local to Cambridge, UK. One a female from an early Anglo-Saxon cemetery a few miles south of the city, dating from 6-7th centuries AD. The other a young adult male from the late 14th century, buried in the grounds of medieval Cambridge’s charitable hospital (later to become St. John’s College), who had suffered appalling dental abscesses. The final sample came from a young adult male excavated in Holland: a fervent clay pipe smoker, most likely massacred by a French attack on his village by the banks of the Rhine in 1672. “We screened ancient DNA samples from around 3,000 archaeological finds and got just four herpes hits,” said co-lead author Dr Meriam Guellil, from Tartu University’s Institute of Genomics. “By comparing ancient DNA with herpes samples from the 20th century, we were able to analyse the differences and estimate a mutation rate, and consequently a timeline for virus evolution,” said co-lead author Dr Lucy van Dorp, from the UCL Genetics Institute. Co-senior author Dr Christiana Scheib, Research Fellow at St. John’s College, University of Cambridge, and Head of the Ancient DNA lab at Tartu University, said: “Every primate species has a form of herpes, so we assume it has been with us since our own species left Africa.” “However, something happened around five thousand years ago that allowed one strain of herpes to overtake all others, possibly an increase in transmissions, which could have been linked to kissing.” The researchers point out that the earliest known record of kissing is a Bronze Age manuscript from South Asia, and suggest the custom – far from universal in human cultures – may have travelled westward with migrations into Europe from Eurasia. In fact, centuries later, the Roman Emperor Tiberius tried to ban kissing at official functions to prevent disease spread, a decree that may have been herpes-related. However, for most of human prehistory, HSV-1 transmission would have been “vertical”: the same strain passing from infected mother to newborn child. Two-thirds of the global population under the age of 50 now carry HSV-1, according to the World Health Organisation. For most of us, the occasional lip sores that result are embarrassing and uncomfortable, but in combination with other ailments – sepsis or even COVID-19, for example – the virus can be fatal. In 2018, two women died of HSV-1 infection in the UK following Caesarean births. “Only genetic samples that are hundreds or even thousands of years old will allow us to understand how DNA viruses such as herpes and monkeypox, as well as our own immune systems, are adapting in response to each other,” said Houldcroft. The team would like to trace this hardy primordial disease even deeper through time, to investigate its infection of early hominins. “Neanderthal herpes is my next mountain to climb,” added Scheib. Publisjhed in Science Advances (July 27, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo4435

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

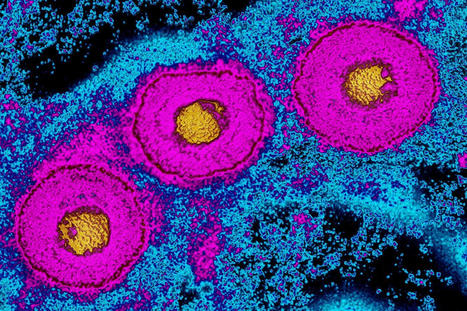

Genes from a virus that was stitched into the human genome thousands of years ago are active, producing proteins in the human brain and other tissues, according to researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine and the Laval University School of Medicine in Quebec, Canada. Their finding might help explain why people who inherit this “fossil virus” appear to have a higher risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s. “There have been some reports that the virus, called human herpesvirus-6, can reactivate, but if it does, it’s rare,” said Dr. Alex Greninger, UW assistant professor of laboratory medicine. “What we wanted to know whether some of the virus’ individual genes were being turned on without full reactivation of the virus.” The Journal of Virology published the article recently. Its lead authors were Vikas Peddu, a bioinformatician in the Greninger lab, and Isabelle Dubuc of Laval University. The project was led by Greninger and Louis Flamand, professor in the microbiology and immunology at Laval. The researchers were interested in two versions of human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6) that can integrate into chromosomes and be inherited like any other human gene. HHV-6B causes the common childhood illness, roseola. This infection affects about 90 percent of children early in life, causing high fevers and rash. However, relatively little is known about the second virus, HHV-6A. After infection, both viruses can remain dormant in the body and reactivate later, particularly in people whose immune systems are suppressed. In the new study, the researchers looked at a form of the virus that is not acquired by infection but which about one in a hundred people inherit as part of their genome. About 8 percent of human DNA comes from viruses inserted into our genomes in the distant past, in many cases into the genomes of our pre-human ancestors millions of years ago. Most of these viral genes come from retroviruses, RNA viruses that insert DNA copies of their own genes into our genomes when they infect cells. HHV-6 is unique because it is the only known human DNA herpesvirus that integrates into the human genome and can be routinely inherited. HHV-6’s genome may have been accidentally copied into the human genome because it has repeating DNA sequences that resemble those found in human chromosomes. In conducting the study, the investigators analyzed a database of genome sequences of 650 people who gave consent before they died for their DNA genomes to be researched. The scientists also had access to cellular RNA in up to 40 tissue samples. “A lot of human genomicists have overlooked these integrated HHV-6 sequences in human genomes. They’re not in the human reference sequences and they’re not common enough to rise on the radar,” Greninger said. The researchers identified six individuals who had HHV-6 integrated in their genomes: two with HHV-6A and four with HHV-6B. The RNA sequences revealed that in these individuals, a number of viral genes were being actively expressed, in particular one gene called U90 and another called U100. In most tissues, the level of expression was low and sporadic, but the highest expressions were found in the esophagus, testes, adrenal gland and brain. The gene U100 codes for a viral protein that is part of the viral outer shell, or envelope. U90 codes for a protein known as a transactivator, which means it promotes the expression of other genes.... Published in Journal of Virology (Open Access)(Oct. 9, 2019) https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01418-19

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A new finding that even took the study’s authors by surprise lends support to the controversial idea that microbes play a role in Alzheimer’s disease. The research published June 21 in Neuron, found convincing signs that certain types of herpes virus may promote the complex process that leads to the disease that afflicts some 5.7 million Americans. The study points to the viruses as possible accomplices that drive disease progression but does not suggest that Alzheimer’s may begin after they are transmitted through casual contact. Joel Dudley, a geneticist and genomic scientist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and senior author of the new paper, had not intended to investigate this theory when his lab began working on the newly published study in 2013. The plan he had made with colleagues was to identify possible new Alzheimer’s drug targets by looking at the molecular changes in the brain that occur during the disease. Thanks to a new NIH-led public-private partnership called the Accelerating Medicines Partnership Alzheimer's Disease (AMP-AD), the team had access to data from 876 brains—some healthy and some with early- or late-stage Alzheimer’s. They used DNA and RNA sequencing to parse out genetic differences between the groups as well as differences in how inherited genes were expressed or made into RNA. That’s when they started getting strange results. “The algorithms kept returning this pattern for viral biology,” Dudley says. The team found more viral DNA in Alzheimer’s brains compared with healthy brains—specifically, high levels of DNA from human herpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A). RNA of both HHV-6A and HHV-7 were also higher in the Alzheimer’s brains than in healthy brains, and viral RNA levels tracked with the severity of clinical symptoms. HHV-6A is a usually symptom-less virus that infects people later in life. HHV-7 infects more than 80 percent of infants, often causing a rash. Original research Published in Neuron on June 21, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.023

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

People who tested positive for the virus behind genital herpes tended to have reduced thickness of their outermost brain layer, which has been linked to Alzheimer's disease. Jose Gutierrez at Columbia University in New York and his colleagues analysed the MRI brain scans and blood test results of 455 adults, aged 70 on average, who took part in a long-term health-tracking study in Manhattan... Study published Oct. 28, 2023: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2023.120856

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

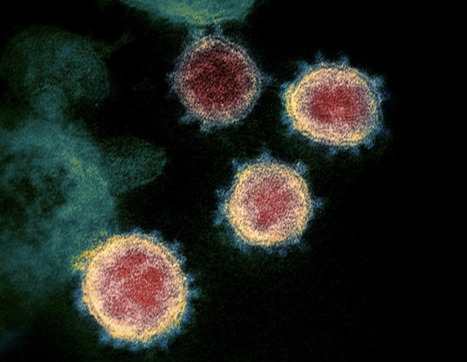

COVID-19 reactivated viruses that had become latent in cells following previous infections, particularly in people with chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as ME/CFS. This is the conclusion of a study from Linköping University in Sweden. The results, published in Frontiers in Immunology, contribute to our knowledge of the causes of the disease and prospects of reaching a diagnosis. Severe, long-term fatigue, post-exertional malaise, pain and sleep problems are characteristic signs of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, “ME/CFS”. The causes of the condition are not known with certainty, although it has been established that the onset in most cases follows a viral or bacterial infection. The health of the person affected is not restored even after the original infection is resolved. Indeed – the condition is sometimes known by its alternative name: post-viral fatigue. Since the cause is not known, diagnostic tests have not been developed. “This patient group has been neglected. Our study now shows that objective measurements are available that show physiological differences in the body’s reaction to viruses between ME patients and healthy controls,” says Anders Rosén, professor emeritus in the Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences (BKV) at Linköping University, and leader of the study. One theory that has been examined in several research studies is that a new infection can activate viruses that lie latent in the body’s cells after a previous infection. It has long been known that several herpes viruses, for example, can remain in a latent state in the body. Latent viruses can be reactivated many years later and give rise to a new bout of disease. It has, however, been difficult to determine whether such reactivated viruses are involved in ME/CFS – until now. The extensive spread of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus during the COVID-19 pandemic has given researchers a unique opportunity to study what happens in people with ME/CFS during a mild virus infection and compare this with what happens in healthy controls. In collaboration with the Bragée Clinic in Stockholm, the research group initiated a study early in the pandemic. Ninety-five patients who had been diagnosed with ME/CFS and 110 healthy controls participated in the study. They provided blood and saliva samples on four occasions during one year. The researchers analysed samples for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and latent viruses, and found a special fingerprint of antibodies against common herpes viruses in saliva. One of these viruses was the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which has infected nearly everybody. Most people experience a mild infection during childhood. People who are infected with EBV in the teenage years can develop glandular fever, commonly called mononucleosis, and also known as “kissing disease”. The virus then remains in a latent condition in the body. The EBV virus may proliferate in situations in which the immune system is impaired, causing fatigue, an autoimmune responses, and increased risk of lymphoma, if allowed to continue. Approximately half of the participants were infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the first wave of the pandemic and developed mild COVID-19 (58% of those with ME/CFS and 41% of the control group). In more than one third of cases, infection had been asymptomatic, so the person had not been aware of the infection. After the SARS-CoV-2 infection had passed, however, the researchers detected specific antibodies in the saliva that suggested that three latent viruses had been strongly reactivated, one of them being EBV. The reactivation was seen both in patients with ME/CFS and in the control group, but was significantly stronger in the ME/CFS group. Anders Rosén describes what happens as a domino effect: infection with a new virus, SARS-CoV-2, can activate other, latent, viruses in the body. The researchers suggest that this can, in turn, give rise to a chain reaction with an elevated immune response. This can have negative consequences, one of which is that the immune system attacks certain tissues, such as nerve tissue, in the body. Previous studies have also shown that the mitochondria, which produce energy in the cells, are affected, which suppresses the energy metabolism of people with ME/CFS. “Another important result from the study is that we see differences in antibodies against the reactivated viruses only in the saliva, not in the blood. This means that we should use saliva samples when investigating antibodies against latent viruses in the future,” says Anders Rosén. He points out that there is a great deal of overlap between the symptoms of ME/CFS and those of long COVID, which is experienced by around one third of patients who contract COVID-19. Exhaustion after light exercise, brain fog and unrefreshing sleep are common symptoms, while impaired lung capacity and abnormal senses of smell and taste are more specific for long COVID. The researchers believe that the results from the study can contribute to developing immunological tests to diagnose ME/CFS, and possibly also long COVID. “We now want to continue and carry out more detailed investigations into the immune response in ME/CFS, and in this way understand the differences between the antibody responses against latent viruses,” says Eirini Apostolou, principal research engineer, and lead author of the article. The study was financially supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society and Linköping University. Some of the authors have financial interests in the Bragée Clinic. Study cited published in Frontiers in Immunology (Oct. 20, 2022): https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.949787

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A genetically edited form of a herpes simplex virus—rewired to keep it from taking refuge in the nervous system and eluding an immune response—has outperformed a leading vaccine candidate in a new study from the University of Cincinnati, Northwestern University and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Published Nov. 6 in the journal Nature Vaccines, the study found that vaccinating guinea pigs with the modified live virus significantly increased the production of virus-combating antibodies. When challenged with a virulent strain of herpes simplex virus, the vaccinated animals displayed fewer genital lesions, less viral replication and less of the viral shedding that most readily spreads infection to others. The modified virus is actually a form of herpes simplex virus type 1, best known for causing cold sores around the lip. The fact that it demonstrated cross-protection against HSV type 2—the sexually transmitted type usually responsible for genital herpes—suggests that an HSV-2-specific edition of the vaccine could prove even more effective, the researchers said. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 500 million people have HSV-2, which persists for a lifetime and often flares up in response to stress. In addition to causing blisters, HSV-2 increases the risk for HIV infection and may contribute to Alzheimer's disease or other forms of dementia. Despite the prevalence of the viruses, more than four decades of research have yet to yield an approved vaccine for HSV-1 or HSV-2. Part of the difficulty: The alphaherpesviruses, which include HSV, have evolved an especially sophisticated way of evading the immune responses aimed at destroying them. After infecting mucosal tissues of the mouth or genitourinary tract, HSV works its way to the tips of sensory nerves that transmit signals responsible for the sensations of pain, touch and the like. With the help of a specialized molecular switch, the virus then breaks into the nerve cell, hitching a ride on the molecular equivalent of a trolley car that transports it along a nerve fiber and into the nucleus of a sensory neuron. Whereas the mucosal infection is soon cleared by the immune response, the infected neurons become a sanctuary from the body's immune system, with HSV leaving only when stirred by rises in steroids or other stress-elevated hormones in the host. Nebraska's Gary Pickard and Patricia Sollars, alongside Northwestern's Gregory Smith and Tufts University's Ekaterina Heldwein, have spent years studying how to prevent HSV from reaching the safety of the nervous system. Heldwein advanced those efforts when she characterized the architecture of a certain alphaherpesvirus protein, pUL37, that the team suspected was integral to the virus moving along nerve fibers. Computer analyses based on that architecture suggested that three regions of the protein might prove important to the process. Smith then carefully plucked out and replaced five codons, the fundamental coding information in the DNA, from the viral genome of each region. The researchers hoped that those mutations might help impede the virus from invading the nervous system. Their hopes were rewarded when Pickard and Sollars injected mice with a virus modified in region 2, or R2, of the protein. Rather than advancing deeper into the nervous system, the virus was stuck at the nerve terminal. But the team also knew that modifying HSV could have unintended consequences. "You can keep the virus from getting into the nervous system," said Pickard, professor of veterinary medicine and biomedical sciences at Nebraska. "That's not that hard to do by making broadly debilitating mutations. But when you knock down the virus so much that it doesn't replicate well, you are not rewarded with a robust immune response that can protect you from future exposures." So the researchers were heartened when further studies showed that the R2-mutated virus performed well as a vaccine in mice. Moreover, it circumvented certain stubborn issues that have cropped up with other vaccine approaches. Some approaches have involved challenging the immune system with only a subset of HSV components, or antigens, priming the body to recognize them but potentially miss others. Some have modified the virus so that it can replicate just once, preventing long-term persistence in the nervous system but also reducing spread in mucosal tissues and, by extension, a stout immune response.... Original study published in Nature Vaccines (Nov. 6, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-020-00254-8

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Oral herpes is a highly prevalent infection caused by herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1). After an initial infection of the oral cavity, HSV-1 remains latent in sensory neurons of the trigeminal ganglia. Episodic reactivation of the virus leads to the formation of mucocutaneous lesions (cold sores), but asymptomatic reactivation accompanied by viral shedding is more frequent and allows virus spread to new hosts. HSV-1 DNA has been detected in many oral tissues. In particular, HSV-1 can be found in periodontal lesions and several studies associated its presence with more severe periodontitis pathologies. Since gingival fibroblasts may become exposed to salivary components in periodontitis lesions, we analyzed the effect of saliva on HSV-1 and -2 infection of these cells. We observed that human gingival fibroblasts can be infected by HSV-1. However, pre-treatment of these cells with saliva extracts from some but not all individuals led to an increased susceptibility to infection. Furthermore, the active saliva could expand HSV-1 tropism to cells that are normally resistant to infection due to the absence of HSV entry receptors. The active factor in saliva was partially purified and comprised high molecular weight complexes of glycoproteins that included secretory Immunoglobulin A. Interestingly, we observed a broad variation in the activity of saliva between donors suggesting that this activity is selectively present in the population. The active saliva factor, has not been isolated, but may lead to the identification of a relevant biomarker for susceptibility to oral herpes. The presence of a salivary factor that enhances HSV-1 infection may influence the risk of oral herpes and/or the severity of associated oral pathologies. Published on PLOS One on October 3, 2019: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223299

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...