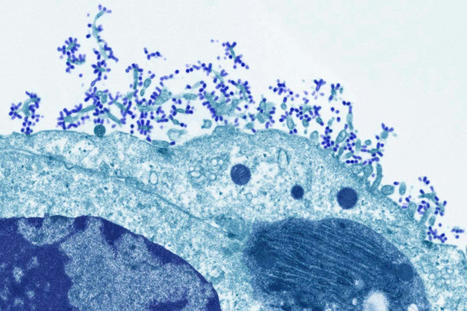

An mRNA vaccine has been found to induce antibody responses against all 20 known subtypes of influenza A and B in mice and ferrets. An experimental vaccine has generated antibody responses against all 20 known strains of influenza A and B in animal tests, raising hopes for developing a universal flu vaccine. Influenza viruses are constantly evolving, making them a moving target for vaccine developers. The annual flu vaccines available now are tailored to give immunity against specific strains predicted to circulate each year. However, researchers sometimes get the prediction wrong, meaning the vaccine is less effective than it could be in those years. Some researchers think annual flu jabs could be replaced by a universal flu vaccine that is effective against all flu strains. Researchers have tried to achieve this by making vaccines containing protein fragments that are common to several influenza strains, but no universal vaccine has yet gained approval for wider use. Now, Scott Hensley at the University of Pennsylvania and his colleagues have created a vaccine based on mRNA molecules – the same approach that was pioneered by the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna covid-19 vaccines. mRNA contains genetic codes for making proteins, just like DNA. The vaccine contains mRNA molecules encoding fragments of proteins found in all 20 known strains of influenza A and B – the viruses that cause seasonal outbreaks each year. The strains have different versions of two proteins on their surface, haemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N), which are targeted by immune responses. But even within one strain, such as H1N1, there can be slight variations in these proteins, so the version in the universal vaccine will not exactly match every possible variant.

In tests in mice, the team found that the animals generated antibodies specific to all 20 strains of the flu virus, and these antibodies remained at a stable level for up to four months. In another test, the team gave mice the universal flu vaccine or a dummy vaccine containing code for a non-flu protein. A month later, they infected them with either one of two variants of the H1N1 flu virus, one with an H1 protein that was very similar to the version of the protein in the vaccine, and one with a more distinct version. All the mice given the flu vaccine survived exposure to the virus with the more similar protein and 80 per cent survived being infected with the more distinct variant. All of the mice given the dummy vaccine died around a week after infection with either variant. Another group of mice were given an mRNA vaccine targeted only to the precise flu strain they were exposed to, and all of this group survived over the same time period. This suggests the universal flu vaccine would offer less protection against new variants of the 20 flu strains than an annual vaccine matched to new forms of the virus, says Albert Osterhaus at the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover in Germany, who wasn’t involved in the study. The researchers also tested the universal vaccine in ferrets with similar results.

“The mouse and ferret models for influenza are as good as animal models get. The animal data are promising and thus a good indication of what will happen in humans,” says Peter Palese at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. A key benefit of mRNA vaccines is that they can easily be scaled up compared with other approaches which rely on growing influenza viruses in chicken eggs or in the lab, says Palese. “For generating a basic immunity against epidemic or pandemic influenza virus strains in the future, this strategy could offer an option if longevity [of immunity] in humans is confirmed,” says Osterhaus. “Definitely these animal data are promising and merit further exploration in clinical studies. Given previous studies with candidate universal flu vaccines in human trials, it is hard to predict what the clinical data will bring,” says Osterhaus. “This 20-HA mRNA vaccine was tested in ferret animals, which is highly significant and may hold promise for protecting against future emerging flu strains against severe disease in humans,” says Sang-Moo Kang at Georgia State University.

Study cited published in Science (Nov. 24):

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...