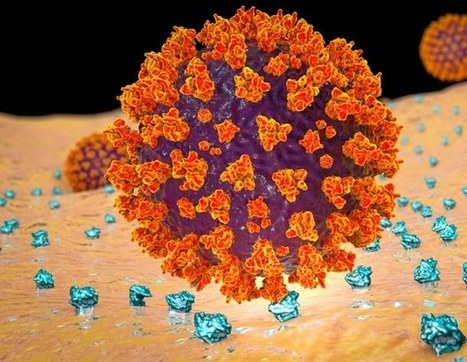

Immune genes could play a part in the risk of needing intensive care when infected with SARS-CoV-2. An analysis of DNA from more than 24,000 people who had COVID-19 and required treatment in intensive care has yielded more than a dozen new genetic links to the risk of developing extreme illness from the disease. The study, which was published on 17 May in Nature1 and has more than 2,000 authors, highlights the role of the immune system in fuelling the later stages of particularly severe COVID-19. The results could one day contribute to the development of therapies for COVID-19 — and potentially other diseases that cause acute respiratory distress or sepsis. “These are likely to be processes that are active in other conditions,” says Kenneth Baillie, an intensive-care specialist at the University of Edinburgh, UK, and lead author on the study. “Everything that we’ve done in COVID will, I think, be relevant to other groups of patients that we haven’t identified yet.”

Team effort

Much of the data were collected from people who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the first waves of the pandemic in the United Kingdom. At that time, many intensive-care staff members were terrified of spending time on the ward, says Baillie. A coronavirus outbreak in 2003 caused by the related virus SARS-CoV had a mortality rate of about 10% and had hit health-care workers particularly hard. “We were nervous,” says Baillie. “Certainly, in the first wave of the pandemic, and for some people in subsequent waves, it seemed like a considerable personal risk.” Despite their fear and the frenzy of providing care at the onset of the pandemic, scores of health-care workers took on the added burden of enrolling participants in studies that investigate how genetics might have contributed to disease severity. Many of the participants were on ventilators, and enrolling them meant long discussions with relatives who were going through some of the most difficult times of their lives, says Baillie. The result was an effort called GenOMICC, which researchers hope will help to improve treatment options for COVID-19 and other conditions in future pandemics. Baillie and his colleagues analysed data from more than 24,000 people and combined this information with data sets from around the world. They found 49 DNA sequences that are associated with becoming critically ill from COVID-19. Sixteen of these had not been reported previously. Among these sequences are some that could affect the activity of genes and proteins involved in the immune system. Raging immune cells have long been implicated in causing some of the tissue damage seen in late-stage, severe cases of COVID-19. Baillie and his colleagues found genetic links to inflammatory responses and the activation of immune cells — processes that can damage the lungs and reduce their capacity to send oxygen to the body’s tissues. “It definitely expands our understanding of the genetic determinants of severe COVID,” says Brent Richards, a human geneticist at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. Richards is an investigator on another project called the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, a global effort in which scientists from more than 54 countries share data. The diversity of that effort will provide a crucial counterpart to the GenOMICC study, which is predominantly drawn from participants of European descent, says Richards.

Reliable results

In addition to the new findings, it is important that the UK study has replicated many of the findings by other groups, says Alexander Hoischen, a geneticist at Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Replication of results across different data sets is crucial when trying to tease apart the possible contribution of common genetic variants to disease. Even so, it will take a great deal of work to show that these variants contribute directly to critical illness — a necessary step to turn these initial findings into new therapies. “That is still a long trajectory,” says Hoischen. But putting together these large consortia of investigators and taking the first steps are considerable triumphs, he adds. In the early days of the pandemic, it was unclear how participation in such large endeavours would benefit the careers of individual scientists. “Many of them acted as purely human beings,” he says, instead of worrying about their careers. “It illustrates the degree of solidarity that we really witnessed in COVID times.”

Cited research published in Nature (May 17, 2023):

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...