Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Genetic analysis of 50,000-year-old Neanderthal skeletons has uncovered the remnants of three viruses related to modern human pathogens, and the researchers think they could be recreated. Genetic sequences from three common viruses that plague humanity today have been isolated from the remains of Neanderthals who lived more than 50,000 years ago. Marcelo Briones at the Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil, says it may be possible to synthesise these viruses and infect modern human cells with them in the lab... Preprint of the study in bioRxiv: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.16.532919

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The post-viral fatigue syndromes long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) have multiple, potentially overlapping, pathological processes. These include persisting reservoirs of virus, e.g., SARS-CoV-2 in long COVID patient’s tissues, immune dysregulation with or without reactivation of underlying pathogens, such as Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6), as we recently described in ME/CFS, and possibly yet unidentified viruses. In the present study we tested saliva samples from two cohorts for IgG against human adenovirus (HAdV): patients with ME/CFS (n = 84) and healthy controls (n = 94), with either mild/asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection or no infection. A significantly elevated anti-HAdV IgG response after SARS-CoV-2 infection was detected exclusively in the patient cohort. Longitudinal/time analysis, before and after COVID-19, in the very same individuals confirmed HAdV IgG elevation after. In plasma there was no HAdV IgG elevation. We conclude that COVID-19 triggered reactivation of dormant HAdV in the oral mucosa of chronic fatigue patients indicating an exhausted dysfunctional antiviral immune response in ME/CFS, allowing reactivation of adenovirus upon stress encounter such as COVID-19. These novel findings should be considered in clinical practice for identification of patients that may benefit from therapy that targets HAdV as well. Published in Frontiers in Medicine (June 29, 2023): https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1208181

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Finding a probable culprit can sometimes happen fairly quickly when something new pops up in the infectious diseases sphere. But that doesn't mean the end of the mystery. I n early April, when word began to circulate that hospitals in the United Kingdom were seeing unexplained hepatitis cases in very young children, some physicians and researchers on this side of the Atlantic experienced a moment of déjà vu. Kevin Messacar and colleagues at Children’s Hospital Colorado found themselves remarking on how reminiscent the unfolding investigation was of a medical mystery they’ve been enmeshed in for the past eight years — acute flaccid myelitis, or AFM, a polio-like condition in children. Meanwhile, Carlos Pardo, the co-principal investigator of a National Institutes of Health study into the natural history of AFM, started fielding queries from hepatologists at Johns Hopkins Medicine, where he teaches, about what kinds of samples they should be collecting from suspected hepatitis cases. “There are many parallels between this initial investigation of these cases of hepatitis of unknown origin and our initial investigations of AFM cases,” Messacar, a pediatric infectious disease physician and an associate professor at the University of Colorado, told STAT. As public health agencies race to figure out what is behind the unusual hepatitis cases, Messacar, Pardo, and others believe there are lessons to be learned from the ongoing efforts to solve the mysteries of AFM. Chief among them is that getting to satisfactory answers is likely going to take time. There may be an answer to the fundamental question of what is causing these illnesses. But the whys and the how — Why now? Why only some children? Why these children? How is the damage being done? — may take considerably longer to resolve. “I think it could be a very difficult nut to crack,” said Michael Osterholm, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Diseases Research and Policy. Finding a probable culprit can sometimes happen fairly quickly when something new pops up in the infectious diseases sphere, said Thomas Clark, deputy director of the division of viral diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clark was the CDC’s incident manager for the AFM investigation in 2018-2019. Such was the case when scientists started investigating AFM, which first pinged on the medical world’s radar in 2012, after California reported a few cases of unexplained paralysis among children. Suspicion soon focused on EV-D68, a member of the enterovirus family that is now generally assumed to be the primary cause of AFM. (Another enterovirus, A71, is also thought to trigger the condition in some cases.) AFM cases occur in very low numbers year round, but have been seen to cluster in every-other-year surges that occurred in 2014, 2016, and 2018. Where in an odd year there may be two or three dozen cases, there were 153 cases and 239 cases in 2016 and 2018, respectively. (Like many other viral illnesses, AFM has been driven to very low levels during the first two years of the Covid-19 pandemic, with an expected spike of cases failing to materialize in 2020.) Settling on a suspect seems to have happened even faster with the unexplained cases of pediatric hepatitis, with many researchers hypothesizing that an adenovirus might be to blame. In the cases, previously healthy children, many under the age of 5, develop severe liver inflammation. Some — about 14% of the cases reported so far in the United States and 10% of those reported in the U.K. — have required liver transplants and a few children have died. The first observed cases occurred last October in Alabama, where five of the state’s eventual nine cases tested positive for an adenovirus. Like enteroviruses, the adenovirus family is large, encompassing about 50 types that infect people. Most cause cold-like illnesses, but a couple are known to infect the gastrointestinal tract. The one spotted by the Alabama physicians was one of the latter, type 41. A substantial portion — though not all — of the roughly 450 cases reported worldwide at this point have tested positive for adenovirus, and in the U.K., more in-depth testing has revealed at least some of those were adenovirus type 41. It remains unclear if this is an incidental finding unrelated to the hepatitis, or if the virus is causing the condition. Investigators are also exploring the question of whether there is some other contributing factor, such as the possibility that two years of pandemic-induced masking and social distancing may have left children’s immune systems inexperienced in fighting off an infection like this one. Another theory is that current or prior Covid-19 infection is amplifying the illness induced by adenovirus infection. As of yet, testing of liver biopsies taken from a number of the suspected cases and from failed livers that were removed from the children who needed transplants has not shown signs of adenovirus infection. Fingering a culprit, though, is only the first step in getting to the bottom of why a small but unusual number of very young children are ending up in hospital with their livers under attack. “It is often true, I guess, that the most commonly implicated virus or the one that’s putatively identified ends up explaining the illness,” said the CDC’s Clark. “But the mechanisms and the why are the challenge to figure out.” Scientists are still working to explain why EV-D68 causes paralysis as well as why it only does so in a tiny fraction of the children it infects.....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Recently, there have been reports of children with a severe acute form of hepatitis in the UK, Europe, the USA, Israel, and Japan. Most patients present with gastrointestinal symptoms and then progress to jaundice and, in some cases, acute liver failure. So far, no common environmental exposures have been found, and an infectious agent remains the most plausible cause. Hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, and E have not been found in these patients, but 72% of children with severe acute hepatitis in the UK who were tested for an adenovirus had an adenovirus detected, and out of 18 subtyped cases in the UK, all were identified as adenovirus 41F. This is not an uncommon subtype, and it predominantly affects young children and immunocompromised patients. However, to our knowledge, adenovirus 41F has not previously been reported to cause severe acute hepatitis. SARS-CoV-2 has been identified in 18% of reported cases in the UK and 11 (11%) of 97 cases in England with available data tested SARS-CoV-2 positive on admission; a further three cases had tested positive within the 8 weeks prior to admission. Ongoing serological testing is likely to yield greater numbers of children with severe acute hepatitis and previous or current SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eleven of 12 of the Israeli patients were reported to have had COVID-19 in recent months, and most reported cases of hepatitis were in patients too young to be eligible for COVID-19 vaccinations. SARS-CoV-2 infection can result in viral reservoir formation. SARS-CoV-2 viral persistence in the gastrointestinal tract can lead to repeated release of viral proteins across the intestinal epithelium, giving rise to immune activation. Such repeated immune activation might be mediated by a superantigen motif within the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein that bears resemblance to Staphylococcal enterotoxin B, triggering broad and non-specific T-cell activation. This superantigen-mediated immune-cell activation has been proposed as a causal mechanism of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Acute hepatitis has been reported in children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome, but co-infection of other viruses was not investigated. We hypothesise that the recently reported cases of severe acute hepatitis in children could be a consequence of adenovirus infection with intestinal trophism in children previously infected by SARS-CoV-2 and carrying viral reservoirs (appendix). In mice, adenovirus infection sensitises to subsequent Staphylococcal-enterotoxin-B-mediated toxic shock, leading to liver failure and death. This outcome was explained by adenovirus-induced type-1 immune skewing, which, upon subsequent Staphylococcal enterotoxin B administration, led to excessive IFN-γ production and IFN-γ-mediated apoptosis of hepatocytes. Translated to the current situation, we suggest that children with acute hepatitis be investigated for SARS-CoV-2 persistence in stool, T-cell receptor skewing, and IFN-γ upregulation, because this could provide evidence of a SARS-CoV-2 superantigen mechanism in an adenovirus-41F-sensitised host. If evidence of superantigen-mediated immune activation is found, immunomodulatory therapies should be considered in children with severe acute hepatitis Published in The Lancet GI and Hepatology (May 13, 2022):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Health officials in the UK have released new details in their ongoing investigation of an unusual series of hepatitis cases in children. The new report helps explain why they have zeroed in on a possible link to the adenovirus family, the UK Health Security Agency announced Monday. Since the beginning of the year, at least 111 children have been identified in the UK with acute liver inflammation that does not appear to be caused by the group of hepatitis viruses that would've been a more likely culprit. Many more cases have been announced in the US and other countries around the world. Roughly three-quarters of the 53 children who were tested for adenovirus in the UK came back positive. The virus that causes Covid-19, on the other hand, was found in only a sixth of children who were tested — in line with the levels of community transmission in the UK. Adenoviruses make up a large family of viruses that can spread from person to person, causing a range of illnesses including colds, pinkeye and gastroenteritis. They are only rarely reported as a cause of severe hepatitis in healthy people. But these hepatitis cases come as the spread of adenovirus has escalated in recent months, along with other common viruses that have surged with the end of Covid-19 prevention measures and behaviors that kept most germs at bay. After falling dramatically during the pandemic, documented adenovirus cases have roared back and are now at higher levels than the UK saw before Covid-19. Although investigations are circling around adenovirus, how it might cause liver inflammation is still unclear. Experts say the virus may be just one factor that leads to these cases when it happens alongside something else. "There may be a cofactor causing a normal adenovirus to produce a more severe clinical presentation in young children," the UK health agency said in its technical briefing Monday, "such as increased susceptibility due to reduced exposure during the pandemic, prior SARS-CoV-2 or other infection, or a yet undiscovered coinfection or toxin. Alternatively, there may have been emergence of a novel adenovirus strain with altered characteristics." Experts say another possibility may be timing. It could be that children who would normally have been infected with minimal symptoms as babies are having more severe reactions to the viruses now that they are older. UK scientists have their sights on a specific type of adenovirus due to blood sample data, but they will need to look at its genetic makeup as confirmation. According to the UK Health Security Agency, the cases are largely in kids under 5, with a median age of 3, and only "a small number of children over the age of ten are being investigated." Dozens have recovered and no deaths have been reported in the UK, but 10 children have needed liver transplants. On Saturday, the World Health Organization said that at least 169 cases of acute hepatitis in children have been identified in 11 countries, including at least 17 liver transplants and one death. In the United States, potential cases have been identified in Alabama, North Carolina and Illinois.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Measures to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2 have also been effective in reducing the transmission of other endemic respiratory viruses. As many countries decrease the use of such measures, we expect that SARS-CoV-2 will circulate with other respiratory viruses, increasing the probability of co-infections. The clinical outcome of respiratory viral co-infections with SARS-CoV-2 is unknown. We examined clinical outcomes of co-infection with influenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, or adenoviruses in 212 466 adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection who were admitted to hospital in the UK between Feb 6, 2020, and Dec 8, 2021, using the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium–WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. Details on patient recruitment, inclusion criteria, testing, and statistical analyses are included in the appendix (pp 2–3). Ethical approval was given by the South Central-Oxford C Research Ethics Committee in England (13/SC/0149), the Scotland A Research Ethics Committee (20/SS/0028), and the WHO Ethics Review Committee (RPC571 and RPC572, April, 2013). Tests for respiratory viral co-infections were recorded for 6965 patients with SARS-CoV-2. Viral co-infection was detected in 583 (8·4%) patients: 227 patients had influenza viruses, 220 patients had respiratory syncytial virus, and 136 patients had adenoviruses. Co-infection with influenaza viruses was associated with increased odds of receiving invasive mechanical ventilation compared with SARS-CoV-2 monoinfection (table). SARS-CoV-2 co-infections with influenza viruses and adenoviruses were each significantly associated with increased odds of death.... Published in the Lancet (March 25, 2022):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a reemerging mosquito-borne virus that causes swift outbreaks. Major concerns are the persistent and disabling polyarthralgia in infected individuals. Here we present the results from a first-in-human trial of the candidate simian adenovirus vectored vaccine ChAdOx1 Chik, expressing the CHIKV full-length structural polyprotein (Capsid, E3, E2, 6k and E1). 24 adult healthy volunteers aged 18–50 years, were recruited in a dose escalation, open-label, nonrandomized and uncontrolled phase 1 trial (registry NCT03590392). Participants received a single intramuscular injection of ChAdOx1 Chik at one of the three preestablished dosages and were followed-up for 6 months. The primary objective was to assess safety and tolerability of ChAdOx1 Chik. The secondary objective was to assess the humoral and cellular immunogenicity. ChAdOx1 Chik was safe at all doses tested with no serious adverse reactions reported. The vast majority of solicited adverse events were mild or moderate, and self-limiting in nature. A single dose induced IgG and T-cell responses against the CHIKV structural antigens. Broadly neutralizing antibodies against the four CHIKV lineages were found in all participants and as early as 2 weeks after vaccination. In summary, ChAdOx1 Chik showed excellent safety, tolerability and 100% PRNT50 seroconversion after a single dose. Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a reemerging mosquito-borne virus that has caused outbreaks in various regions of the world. Here the authors present safety and immunogenicity data from a phase 1 trial with the simian adenovirus vectored vaccine ChAdOx1 Chik, showing induction of neutralizing antibodies to four CHIKV lineages. Published in Nat. Communications (July 30, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24906-y

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Scientists at Johnson & Johnson (JNJ.N) on Friday refuted an assertion in a major medical journal that the design of their COVID-19 vaccine, which is similar AstraZeneca's (AZN.L), may explain why both have been linked to very rare brain blood clots in some vaccine recipients. The United States earlier this week paused distribution of the J&J vaccine to investigate six cases of a rare brain blood clot known as cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), accompanied by a low blood platelet count, in U.S. women under age 50, out of about 7 million people who got the shot. The blood clots in patients who received the J&J vaccine bear close resemblance to 169 cases in Europe reported with the AstraZeneca vaccine, out of 34 million doses administered there. Both vaccines are based on a new technology that uses a modified version of adenoviruses, which cause the common cold, as vectors to ferry instructions to human cells. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is scrutinizing this design behind both vaccines to see if it is contributing to the risk. In a letter on Friday in the New England Journal of Medicine, J&J scientists refuted a case report published earlier this week by Kate Lynn-Muir and colleagues at the University of Nebraska, who asserted that the rare blood clots "could be related to adenoviral vector vaccines." In an interview with Reuters on Thursday, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the top U.S. infectious disease expert and an adviser to the White House, said the fact that they are both adenovirus vector vaccines is a “pretty obvious clue” that the cases could be linked to the vector. "Whether that is the reason, I can't say for sure, but it certainly is something that raises suspicion," Fauci said. In the correspondence on Friday, Macaya Douoguih, a scientist with J&J's Janssen vaccines division, and colleagues pointed out that the vectors used in its vaccine and the AstraZeneca shot are "substantially different" and that those differences could lead to "quite different biological effects." Specifically, they noted that the J&J vaccine uses a human adenovirus while the AstraZeneca vaccine uses a chimpanzee adenovirus. The vectors are also from different virologic families or species, and use different cell receptors to enter cells. The J&J shot also includes mutations to stabilize the so-called spike protein portion of the coronavirus that the vaccine uses to produce an immune response, while the AstraZeneca vaccine does not. "The vectors are very different," said Dr. Dan Barouch of the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Harvard’s Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center in Boston, who helped design the J&J vaccine. "The implications of issues with one vector for the other one are not clear at this point," he said in an interview earlier this week. The J&J scientists said in the letter there was not enough evidence to say their vaccine caused the blood clots and they continue to work with health authorities to assess the data. A panel of advisers to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are expected to meet on April 23 to determine whether the pause on use of the J&J vaccine can be lifted. Letter from J&J published in NEJM (April 15, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2106075

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Adenovirus vectors deliver the genetic instructions for SARS-CoV-2 antigens directly into patients' cells, provoking a robust immune response. But will pre-existing immunity from common colds take them down? Six vaccine candidates in clinical trials for COVID-19 employ viruses to deliver genetic cargo that, once inside our cells, instructs them to make SARS-CoV-2 protein. This stimulates an immune response that ideally would protect recipients from future encounters with the actual virus. Three candidates rely on weakened human adenoviruses to deliver the recipe for the spike protein of the pandemic coronavirus, while two use primate adenoviruses and one uses measles virus. Most viral vaccines are based on attenuated or inactivated viruses. An upside of using vectored vaccines is that they are easy and relatively cheap to make. The adenovirus vector, for example, can be grown up in cells and used for various vaccines. Once you make a viral vector, it is the same for all vaccines, says Florian Krammer, a vaccinologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “It is just the genetic information in it that is different,” he explains. Once inside a cell, viral vectors hack into the same molecular system as SARS-CoV-2 and faithfully produce the spike protein in its three dimensions. This resembles a natural infection, which provokes a robust innate immune response, triggering inflammation and mustering B and T cells. But the major downside to the human adenoviruses is that they circulate widely, causing the common cold, and some people harbor antibodies that will target the vaccine, making it ineffective. CanSino reported on its Phase II trial this summer of its COVID-19 vaccine that uses adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5). The company noted that 266 of the 508 participants given the shot had high pre-existing immunity to the Ad5 vector, and that older participants had a significantly lower immune response to the vaccine, suggesting that the vaccine will not work so well in them. “The problem with adenovirus vectors is that different populations will have different levels of immunity, and different age groups will have different levels of immunity,” says Nikolai Petrovsky, a vaccine researcher at Flinders University in Australia. Also, with age, a person accumulates immunity to more serotypes. “Being older is associated with more chance to acquire Ad5 immunity, so those vaccines will be an issue [with elderly people],” Krammer explains. Moreover, immunity against adenoviruses lasts for many years. “A lot of people have immunity to Ad5 and that impacts on how well the vaccine works,” says Krammer. In the US, around 40 percent of people have neutralizing antibodies to Ad5. As part of her work on an HIV vaccine, Hildegund Ertl of the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia previously collected serum in Africa to gauge resistance levels to this and other serotypes. She found a high prevalence of Ad5 antibodies in sub-Saharan Africa and some West African countries—80 to 90 percent. A different group in 2012 reported that for children in northeast China, around one-quarter had moderate levels and 9 percent had high levels of Ad5 antibodies. “I don’t think anyone has done an extensive enough study to do a world map [of seroprevalence],” notes Ertl. J&J’s Janssen is using a rarer adenovirus subtype, Ad26, in its COVID-19 vaccine, reporting in July that it protects macaques against SARS-CoV-2 and in September that it protects against severe clinical disease in hamsters. Ad26 neutralizing antibodies are uncommon in Europe and the US, with perhaps 10–20 percent of people harboring antibodies. They are more common elsewhere. “In sub-Saharan Africa, the rates are ranging from eighty to ninety percent,” says Ertl. Also critical is the level of antibodies in individuals, notes Dan Barouch, a vaccinologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School. For instance, there was no neutralizing of Ad26-based HIV and Ebola vaccines in more than 80,000 people in sub-Saharan Africa, he says. “Ad26 vaccine responses do not appear to be suppressed by the baseline Ad26 antibodies found in these populations,” because the titres are low, Barouch writes in an email to The Scientist. Barouch has long experience with Ad26-based vaccines and collaborates with J&J on their COVID-19 vaccine. The Russian Sputnik V vaccine, approved despite no published data or Phase 3 trial results, starts with a shot of Ad26 vector followed by a booster with Ad5, both of which carry the gene for the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. This circumvents a downside of viral vector vaccines, specifically, once you give the first shot, subsequent injections will be less efficacious because of antibodies against the vector. Ertl says she has no idea of the proportion of the Russian population with Ad26 or Ad5 antibodies, and there seems to be little or no published data from countries that have expressed interested in this virus, such as Venezuela and the Philippines...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The country’s regulators became the first in the world to approve a possible vaccine against the virus, despite warnings from the global authorities against cutting corners . A Russian health care regulator has become the first in the world to approve a vaccine for the coronavirus, President Vladimir V. Putin announced on Tuesday, though the vaccine has yet to complete clinical trials. The Russian dash for a vaccine has already raised international concerns that Moscow is cutting corners on testing to score political and propaganda points. Mr. Putin’s announcement came despite a caution last week from the World Health Organization that Russia should not stray from the usual methods of testing a vaccine for safety and effectiveness. Mr. Putin’s announcement became essentially a claim of victory in the global race for a vaccine, something Russian officials have been telegraphing for several weeks now despite the absence of published information about any late-phase testing. “It works effectively enough, forms a stable immunity and, I repeat, it has gone through all necessary tests,” Mr. Putin told a cabinet meeting Tuesday morning. He thanked the scientists who developed the vaccine for “this first, very important step for our country, and generally for the whole world.” Western regulators have said repeatedly that they do not expect a vaccine to become widely available before the end of the year at the earliest. Regulatory approval in Russia, well ahead of that timeline, could become a symbol of national pride and provide a much needed political lift for Mr. Putin. The Russian vaccine, along with many others under development in a number of countries in the effort to alleviate a worldwide health crisis that has killed at least 734,900 people, sped through early monkey and human trials with apparent success. Vaccines generally go through three stages of human testing before being approved for widespread use. The first two phases test the vaccine on relatively small groups of people to see if it causes harm and if it stimulates the immune system. The last phase, known as Phase 3, compares the vaccine to a placebo in thousands of people. This final phase is the only way to know with statistical certainty whether a vaccine prevents an infection. And because it’s testing a much larger group of people, a Phase 3 trial can also pick up more subtle side effects of a vaccine that earlier trials could not. The Food and Drug Administration in the United States has said that a new coronavirus vaccine would need to be 50 percent more effective than a placebo in order to be approved. The Russian scientific body that developed the vaccine, the Gamaleya Institute, has yet to conduct Phase III tests on tens of thousands of volunteers in highly controlled trials, a process seen as the only method of ensuring a vaccine is actually safe and effective. Around the world, more than 30 vaccines out of a total of more than 165 under development are now in various stages of human trials. The Russian vaccine uses two strains of adenovirus that typically cause mild colds in humans. They are genetically modified to cause infected cells to make proteins from the spike of the new coronavirus. The approach is similar to a vaccine developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca that has shown promise in early testing and is now undergoing Phase III tests in Britain, Brazil and South Africa.....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

A Covid-19 vaccine candidate being developed by a Chinese drug maker appeared to induce an immune response in subjects, but also showed some concerning although not unexpected results. Data on the vaccine, made by CanSino Biologics, were published Friday in the Lancet, the first time Phase 1 trial data from any Covid-19 vaccine have been published in a scientific journal. The results are likely to be closely examined, particularly in Canada, which recently announced it would test the vaccine and produce it there if results of the early studies were positive. The study found that one dose of the vaccine, tested at three different levels, appeared to induce a good immune response in some subjects. But about half of the volunteers — people who already had immunity to the backbone of the vaccine — had a dampened immune response. The vaccine is what’s known as a viral vector vaccine; it uses a live but weakened human cold virus, adenovirus 5, onto which genetic material of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus has been fused. The Ad5 virus is effectively a delivery system that teaches the immune system to recognize the coronavirus. But many people have had previous infections with adenovirus 5, raising concerns that the immune system would focus on the Ad5 parts of the vaccine rather than the SARS-Cov-2 part. Many research groups that work on viral-vectored vaccines stopped using Ad5 because of concerns about preexisting immunity, which can run to 70% or higher in some populations. “This is definitely one of the concerns about using vectored vaccines for which people might already have pre-existing immunity,” said Michael Mina, an infectious diseases epidemiologist at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “If you already have seen a virus or have some pre-existing immunity to it … you run the risk of having your immune response get skewed and picking up primarily the thing you’re already immune to or that you’ve already seen and not focusing so much on the new aspect, which in this case would be the coronavirus proteins that were placed onto the adenovirus vector,” he said. In the study, Chinese scientists reported that while people who had high levels of preexisting immunity to Ad5 responded to the vaccine, the rise in antibodies to the SARS-Cov-2 virus was less robust than among those in the study who had low or no preexisting antibodies to Ad5. They also showed antibodies to the adenovirus itself soared among people who had prior immunity, suggesting their systems views the vaccination as a boost of their Ad5 immunity..... Studiy Published in The Lancet (May 22, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31208-3

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Large-scale study to identify human adenovirus genotypes in Singapore leads to discovery of four new adenovirus strains and increase in strains linked to severe diseases. Researchers suggest use of antiviral therapies and adenovirus vaccines, and routine monitoring of adenovirus strains. Human adenovirus (HAdV) infections in Singapore and Malaysia have caused severe respiratory disease among children and adults in recent years, but scientists still don't know whether these outbreaks are due to new or re-emerging virus strains. In the first large-scale study to systematically identify HAdV strains in Singapore, scientists led by Duke-NUS Medical School have discovered four new strains and found an increase in two strains linked to severe diseases. Using a genotyping algorithm to study HAdV infections among patients from two large public hospitals in Singapore, the researchers tested over 500 clinical samples from paediatric and adult patients. "We detected four new HAdV strains closely related to a strain isolated from an infant in Beijing during an epidemic in 2012-2013," said the study's lead author, Dr Kristen Coleman, from the Emerging Infectious Diseases (EID) Programme at Duke-NUS Medical School. "Our results also highlight an increase in HAdV types 4 and 7 among the paediatric population over time. Importantly, patients with weakened immune systems and those with HAdV types 2, 4 or 7 were more likely to experience severe disease." Adenoviruses are a family of viruses with over 50 known strains that can infect people of all ages and most commonly infect the respiratory system. The sore throat and fever associated with the common cold are among the symptoms brought about by different adenovirus strains. In some cases, particularly in patients with weakened immune systems, adenoviruses can cause severe respiratory symptoms, including pneumonia, or more life-threatening conditions like organ failure. "The high prevalence and severity of HAdV type 4 infections identified in our study is intriguing," stated Dr Gregory Gray, senior and corresponding author of the study, who is a professor in the EID Programme at Duke-NUS and member of the Duke Global Health Institute at Duke University, USA. "Upon its discovery in the 1950s, HAdV type 4 was largely considered restricted to and controlled by vaccine in the US military population, with rare detections among civilians. Singapore would benefit from more frequent studies of clinical HAdV genotypes to identify patients at risk for severe disease and help guide the use of new antiviral therapies." Given the study results, the authors suggest public health officials and clinicians in Singapore consider using antiviral therapies and adenovirus vaccines. Furthermore, they recommend Singapore and other countries considering new HAdV treatment and control measures conduct periodic and routine adenoviral genotype surveillance to collect the data needed to make informed, evidence-based decisions. Published in J. Infectious Disease (Sept. 30, 2019): https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz489

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Efforts to develop an effective HIV vaccine have repeatedly stumbled on one tough research strain, SIVmac239. Nicknamed the 'death star' strain, it has defeated multiple anti-HIV vaccine and antibody candidates, until now. Scientists have just beaten the 'death star' with a gene-therapy-style, nontraditional vaccine that prompts muscle cells to manufacture protective proteins. A team at the Scripps Research Florida campus reports successfully beating that challenge. In a paper published in the journal Science Translational Medicine today, lead authors Michael Farzan, PhD, and Mathew Gardner, PhD, describe their destruction of the "death star" strain and another especially hard-to-fight strain, suggesting it may be possible to protect uninfected individuals from multiple forms of HIV. Their nontraditional vaccine achieved another critical goal: durability. This means it protected the research animals from infection long-term, with a single inoculation, Farzan says. "We have solved two problems that have plagued HIV vaccine studies to date -- namely, the absence of duration of response and the absence of breadth of response," Farzan says. "No other vaccine, antibody or biologic protects against the two viruses for which we have demonstrated robust protection." Conventional vaccine approaches typically use a piece of virus or other immunogen to activate an immune system response. Because HIV replicates and changes so quickly, that approach has proven challenging. Farzan's approach uses a safe virus to fight the dangerous one, and relies on muscle cells rather than immune cells to generate protective agents. Here's how: A harmless, lab-made adeno-associated virus (AAV) carries within it a protective protein designed by Farzan and colleagues to stop HIV infectivity. Called eCD4-Ig, the protective protein features two HIV co-receptors, CD4 and CCR5. The latter was discovered by Farzan and his team over a decade ago. Farzan's viral vaccine is injected into muscle. It "infects" the muscle cells, which causes them to produce the protective eCD4-Ig. During exposure to HIV, the HIV virus is attracted to eCD4-Ig. It binds, and then "undergoes conformational change prematurely, and it's no longer able to infect," Farzan says.... The study was published on July 24 in the journal Science Translational Medicine: https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aau5409

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The new observation, made by UNC School of Medicine’s Stephan Moll, MD, and Jacquelyn Baskin-Miller, MD, suggests that a life-threatening blood clotting disorder can be caused by an infection with adenovirus, one of the most common respiratory viruses in pediatric and adult patients. CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Platelets, or thrombocytes, are specialized cellular fragments that form blood clots when we get scrapes and traumatic injuries. Viral infections, autoimmune disease, and other conditions can cause platelet levels to drop throughout the body, termed thrombocytopenia. After a robust clinical and research collaboration, Stephan Moll, MD, and Jacquelyn Baskin-Miller, MD, both in the UNC School of Medicine, have linked adenovirus infection with a rare blood clotting disorder. This is the first time that the common respiratory virus, which causes mild cold-and flu-like symptoms, has been reported to be associated with blood clots and severe thrombocytopenia. “This adenovirus-associated disorder is now one of four recognized anti-PF4 disorders,” said Moll, professor of medicine in the Department of Medicine’s Division of Hematology. “We hope that our findings will lead to earlier diagnosis, appropriate and optimized treatment, and better outcomes in patients who develop this life-threatening disorder.” Their new observation, which was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, sheds new light on the virus and its role in causing an anti-platelet factor 4 disorder. Additionally, the discovery opens a whole new door for research, as many questions remain as to how and why this condition occurs – and who is most likely to develop the disorder. HIT, VITT, and “Spontaneous HIT” Antibodies are large Y-shaped proteins that can stick to the surface of bacteria and other “foreign” substances, flagging them for destruction by the immune system or neutralizing the threat directly. In anti-PF4 disorders, the person’s immune system makes antibodies against platelet factor-4 (PF4), a protein that is released by platelets. When an antibody forms against PF4 and binds to it, this can trigger the activation and rapid removal of platelets in the bloodstream, leading to blood clotting and low platelets, respectively. Sometimes, the formation of anti-PF4 antibodies is triggered by a patient’s exposure to heparin, called heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), and sometimes it occurs as an autoimmune condition without heparin exposure, which is referred to as “spontaneous HIT.” In the last three years, thrombocytopenia has been shown to rarely occur after injection with COVID-19 vaccines that are made with inactivated pieces of an adeno–viral vector. These vaccines are different than the ones made in the United States, such as those by Moderna and Pfizer. The condition is referred to as vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT). The Road to Discovery The road to the discovery started when a young child, who had been diagnosed as an outpatient with adenovirus infection, had to be admitted to the hospital with an aggressive blood clot forming in his brain (called cerebral sinus vein thrombosis) and severe thrombocytopenia. Doctors determined that they hadn’t been exposed to heparin or the adeno-vector COVID-19 vaccination, the classical triggers for HIT and VITT. “The intensive care unit physicians, the neuro-intensivist, and hematology group were working around the clock to determine next steps in the care for this young child,” said Baskin-Miller. “They weren’t responding to therapy and were progressing quickly. We had questioned whether it could have been linked to the adenovirus considering the vaccine data, but there was nothing in the literature at that time to suggest it.” The collaborative clinical effort to help the patient expanded: Baskin-Miller reached out to Moll, who is an expert in thrombosis and has various connections throughout the field. To Moll, it looked like the pediatric patient could have “spontaneous HIT”. They then tested for the HIT platelet activating antibody, which came back positive. Collaboration is Key Moll reached out to, Theodore E. Warkentin, MD, a professor of pathology and molecular medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, who has been researching anti-PF4 disorders for three decades, to hear if he was aware of an association between adenoviral infection and spontaneous HIT. Warkentin, who is one of the premier international anti-PF-4 disorders researcher, wasn’t aware of the condition. Around the same time, Moll received a phone call from Alison L. Raybould, MD, a hematologist-oncologist in Richmond, Virginia, a previous trainee from UNC. She was seeing a patient who had multiple blood clots, a stroke and heart attack, arm and leg deep-vein thromboses (DVT), and severe thrombocytopenia. The patient had not been exposed to heparin or vaccines. However, this patient’s severe illness had also started with viral symptoms of cough and fever, and she had tested positive for adenoviral infection. Testing for an anti-PF4 antibody also turned out to be positive. To help clarify the diagnoses of the two patients, Warkentin immediately offered to further test the patients’ blood and samples were directly to his laboratory in the Hamilton General Hospital for further study. They confirmed that the antibodies were targeting platelet factor 4, much like the HIT antibodies. Surprisingly, the antibody resembled that of the VITT and bound to PF4 in the same region as VITT antibodies do. They concluded that both the patients had “spontaneous HIT” or a VITT-like disorder, associated with an adenovirus infection. More Questions Following such a groundbreaking conclusion, Moll and colleagues are now left with many questions about the prevalence of the new anti-PF4 disorder, whether the condition can be caused by other viruses, and why this condition doesn’t occur with every infection with adenovirus. They also wonder what preventative or treatment measures can be made to help patients who develop the new, potentially deadly anti-PF4 disorder. “How common is the disorder?” asked Moll. “What degree of thrombocytopenia raises the threshold to test for anti-PF4 antibodies? And then finally, how do we best treat these patients to optimize the chance that they will survive such a potentially deadly disease?” Media contact: Kendall Daniels, Communications Specialist, UNC Health | UNC School of Medicine Original research published in New England J. Medic. (August 10, 2023): https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2307721

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Infection with multiple common viruses may be responsible for the cases that puzzled doctors last year. Last year, reports of severe, unexplained hepatitis in previously healthy children puzzled health experts around the world. Now, a small new study of American children adds to the evidence that the cases, which remained extremely rare, may have been caused by a simultaneous infection with multiple common viruses, including one known as adeno-associated virus type 2, or AAV2. AAV2 is not typically associated with disease, and it requires a second “helper” virus in order to replicate. Many of the children with unexplained hepatitis, or liver inflammation, were infected with multiple helper viruses, the researchers found. Although the idea remains speculative, the timing of the outbreak may have been related to the loosening of pandemic precautions, leaving large numbers of young children exposed to common viruses they had not previously encountered. “It may have resulted in a population that was highly vulnerable to getting infected with multiple viral infections,” said Dr. Charles Chiu, an infectious disease specialist and microbiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and an author of the new study. The research appeared Thursday in the journal Nature, alongside two British studies that also implicated AAV2 in the hepatitis cases. Preliminary versions of the British studies were posted online last summer. The consistent findings are “quite striking,” said Dr. Frank Tacke, head of the gastroenterology and hepatology department at the Charité University Medical Center in Berlin, who was not involved in the research but wrote an accompanying commentary. “The fact that three independent groups found this from different areas of the world actually makes it really convincing.” Still, the findings are not definitive, and many uncertainties remain, including how these infections might trigger hepatitis and whether AAV2 plays a causal role or is “just a bystander,” Dr. Tacke said. (There has also been some debate about whether the cases truly became more commonlast year or whether they were part of a previously unrecognized phenomenon.) The cases date back to the fall of 2021 but seemed to peak last spring and summer before tapering off, experts said. By last July, more than 1,000 probable cases had been reported in 35 countries, including the United States, according to the World Health Organization. Roughly 5 percent of children required liver transplants, and 2 percent died. In several early studies, scientists found that many of the affected children were infected with adenoviruses, particularly adenovirus 41, which typically causes gastrointestinal symptoms. Adenoviruses are not typically known to cause hepatitis in otherwise healthy children, but they are common helper viruses for AAV2. The new study was a collaboration among academic researchers, state health departments and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among other institutions. The researchers studied biological samples from 16 American children, from six states, with unexplained hepatitis. All had previously tested positive for an adenovirus. They also studied samples from 113 control children, a group that included healthy children, children with gastroenteritis and children with hepatitis from a known cause. Blood samples were available from 14 of the children with unexplained hepatitis. The researchers found AAV2 in 13 of those children, or 93 percent of them, compared with 3.5 percent of control children. Among the 30 children who had hepatitis linked to a known cause, none tested positive for AAV2. Most of the children with unexplained hepatitis also tested positive for at least one herpes virus, which means that many were infected by at least three viruses: AAV2, an adenovirus and a herpes virus In the British studies, which were also small, scientists found AAV2 in the blood and livers of affected children. Many were also infected with an adenovirus or herpes virus. In one study, 25 of 27 affected children shared an immune-related genetic variant that is relatively uncommon in the general population. The finding suggests that this variant might predispose some children to hepatitis when they are infected by AAV2 and one or more helper viruses. “It may turn out that in rare cases, you have kind of a perfect storm of events, where there’s a subset of children who were uniquely susceptible,” Dr. Chiu said. More research is necessary to determine whether one or more of these viruses were injuring the liver directly, he said. An alternative explanation is that, in a small subset of children, infection with multiple viruses triggers an overly strong immune response, which damages the liver. Nailing down the mechanism would have important implications for treatment, Dr. Tacke added. If the viruses are damaging the liver, then antivirals might be the best course of treatment; if an immune overreaction is to blame, then suppressing the immune response with steroids might be a better choice, he said. Research cited published (March 30, 2023) in Nature: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05949-1

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Recently, the Centers for Diseases and Control released a nationwide health alert about an increase in hepatitis cases of unknown origin in children, raising concern about potential sequelae of COVID-19 infection. In this study, we test whether there was increased risk of elevated serum liver enzymes and bilirubin following COVID-19 infection in children. We performed a retrospective cohort study on a nation-wide database of patient electronic health records (EHRs) in the US. The study population comprise 796,369 children between the ages of 1-10 years including 245,675 who had contracted COVID-19 during March 11, 2020 - March 11, 2022 and 550,694 who contracted non-COVID other respiratory infection (ORI) during the same timeframe. Compared to children infected with other respiratory infections, children infected with COVID- 19 infection were at significantly increased risk for elevated AST or ALT (hazard ratio or HR: 2.52, 95% confidence interval or CI: 2.03-3.12) and total bilirubin (HR: 3.35, 95% CI: 2.16- 5.18). These results suggest acute and long-term hepatic sequelae of COVID-19 in pediatric patients. Further investigation is needed to clarify if post-COVID-19 related hepatic injury described in this study is related to the current increase in pediatric hepatitis cases of unknown origin. Preprint iin medRxiv (May 14, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.10.22274866

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

This briefing is produced to share data useful to other public health investigators and academic partners undertaking related work. Although a detailed clinical case review is also taking place, that data is not shared here as, given the small number of cases, there are some risks to confidentiality. Cases As of 3 May 2022, there have been 163 cases of acute non-A-E hepatitis with serum transaminases greater than 500 IU/l identified in children aged under 16 years old in the UK since 1 January 2022. This is the result of an active case finding investigation commencing in April which identified retrospective as well as prospective cases. Eleven cases have received a liver transplant. No cases resident in the UK have died. New cases continue to be identified. Whilst there is some apparent reduction in confirmed cases in the past 2 weeks overall in the UK, there are continued new case reports in Scotland, the number of cases pending classification in England is substantial and the likely reporting lags mean that we cannot yet say there is a decrease in new cases. Cases pending classification are usually those in which laboratory testing to rule out known causes of hepatitis has not been completed. Working hypotheses The working hypotheses have been refined. The leading hypotheses remain those which involve adenovirus. However, we continue to investigate the potential role of SARS-CoV-2 and to work on ruling out any toxicological component. Associated pathogens Adenovirus remains the most frequently detected potential pathogen. Amongst 163 UK cases, 126 have been tested for adenovirus of which 91 had adenovirus detected (72%). Amongst cases the adenovirus has primarily been detected in blood. On review of some of the adenovirus negative cases it was notable that some had only been tested on respiratory or faecal samples, and some had been tested on serum or plasma rather than whole blood (whole blood being the optimal sample). It is therefore not possible to definitively rule out adenovirus in these cases. SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in 24 cases of 132 with available results (18%). SARS-CoV-2 serological testing is in process. A range of other possible pathogens have been detected in a low proportion of cases and are of uncertain significance, although the inclusive nature of the UKHSA case definition intentionally will pick up some cases of non-A-E hepatitis with recognised causes. Adenovirus characterisation Typing by partial hexon gene sequencing consistently shows that the adenovirus present in blood is type 41F (18 of 18 cases with an available result). Whole genome sequencing (WGS) has been attempted on multiple samples from cases but the low viral load in blood samples, and limited clinical material from historic cases, mean that it has not been possible to get a good quality full adenovirus genome from a case as yet. Metagenomics Metagenomics undertaken on blood and liver tissue has detected primarily adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV-2) in high quantities. Whilst contamination was originally suspected, AAV-2 is now detected in multiple samples from different hospital sources and tested in more than one sequencing laboratory. This finding is of uncertain significance and may represent a normal reactivation of AAV-2 during an acute viral infection (for example, adenovirus) or during liver injury of another cause. It is not unusual to detect bystander, reactivating or other incidental species during metagenomic sequencing. However, given the presence of AAV-2 in a number of cases, the significance will be further explored through testing of additional sets of controls. Toxicology Toxicological investigations continue with no positive findings to date. Detection of paracetamol is likely to be related to appropriate therapeutic use (also noted in the trawling questionnaires) which would not be a concern, however verification work is being undertaken to confirm this. Host investigations Host (for example, immunological) investigations require full research consent and are undertaken under the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) Clinical Characterisation Protocol. Thirty-seven cases have been recruited to the ISARIC clinical characterisation protocol to date and retrospective and prospective recruitment continues... Update 2 (May 6, 2022): https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1073704/acute-hepatitis-technical-briefing-2.pdf

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Researchers suspect an adenovirus may be involved, but are still searching for the cause of illness. Puzzled scientists are searching for the cause of a strange and alarming outbreak of severe hepatitis in young children, with 74 cases documented in the United Kingdom and three in Spain. Clinicians in Denmark and the Netherlands are also reporting similar cases. And in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said late yesterday it is investigating nine cases in Alabama. Viruses can cause hepatitis, an inflammation of the liver, but otherwise-healthy children rarely become seriously ill. As of 12 April, none of the U.K. or Spanish children have died, but some are very sick: All have been admitted to hospitals and seven required liver transplants, six of them in the United Kingdom, according to a World Health Organization (WHO) statement issued today. Two of the nine affected children in Alabama have required liver transplants, the state’s Department of Public Health announced this afternoon. The leading theory is that an adenovirus, a family of viruses that more typically cause colds, is the culprit—up to half of the sickened children in the United Kingdom tested positive for such a virus, as did all the children in Alabama. But so far, the evidence is too thin to resolve the mystery, researchers and physicians say. “This is a severe phenomenon,” says Deirdre Kelly, a pediatric hepatologist at Birmingham Children’s Hospital in the United Kingdom. “These [were] perfectly healthy children … up to a week ago.” Not all the news is bad, however. “Most of [the children] recover on their own,” Kelly notes. “This should be taken seriously,” WHO’s Regional Office for Europe wrote in an emailed statement. “The increase is unexpected and the usual causes have been excluded.” Scottish investigators first identified the outbreak on 31 March, when they alerted Public Health Scotland to a cluster of 3- to 5-year-olds admitted to the Royal Hospital for Children in Glasgow in the first 3 weeks of March. Each was diagnosed with severe hepatitis of unknown cause. Typically, Scotland sees fewer than four such cases annually, the investigators wrote in a paper published yesterday. But there have been 13 cases in Scottish children as of 12 April, all but one in March and April. Kelly, who works at one of England’s three centers for pediatric liver disease and transplantation, says that since the start of this year, her unit has seen 40 cases of childhood hepatitis of uncertain cause. Over the same January to April period in 2018, her unit saw only seven such children. Most of the U.K. children are 2 to 5 years old, according to a statement issued on 8 April by the UK Health Security Agency. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control issued a public alert on 12 April about the U.K. outbreak, noting that vomiting and jaundice—yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes—are common symptoms. Early hypotheses about what might be making the children sick included a toxic exposure from food, drinks, or toys, but suspicion now centers on a virus. None of the U.K. or Spanish kids had the hepatitis A, B, C, or E viruses, typical infectious causes of the disease. But a handful of children tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection shortly before or upon hospital admission; none had received a COVID-19 vaccine. In addition, as many as half had adenovirus, a common virus passed by respiratory droplets and from touching infected people or virus on surfaces. It can cause vomiting, diarrhea, conjunctivitis, and cold symptoms but rarely causes hepatitis. “The leading hypotheses center around adenovirus—either a new variant with a distinct clinical syndrome or a routinely circulating variant that is more severely impacting younger children who are immunologically naïve,” the Scottish investigators wrote. Isolation of the youngest children during the pandemic lockdown may have left them immunologically vulnerable because they haven’t been exposed to the multiplicity of viruses, including adenoviruses, that typically attend toddlerhood. “We are seeing a surge in typical childhood viral infections as children come out of lockdown, [as well as] a surge in adenovirus infections”—but can’t be sure that one is causing the other, says Will Irving, a clinical virologist at the University of Nottingham. Researchers continue to study other possibilities. For example, the immunological effects of a prior episode of COVID-19 might have left children more vulnerable to infection or the illness could be a long-term complication of COVID-19 itself. An unidentified toxin has also not been ruled out. All the cases might not have a single cause, cautions Jim McMenamin, an epidemiologist who heads the infection service of Public Health Scotland. “It’s awfully important that we ensure we are looking for everything, that we are not confining ourselves to saying this is simply one viral cause.” In the United States, CDC is helping the Alabama Department of Public Health investigate nine cases of hepatitis in children ranging in age from 1 to 6 years old and who also tested positive for adenovirus. The cases have occurred since October 2021, Kristen Nordlund, a CDC spokesperson, wrote in the statement emailed to ScienceInsider last night. “CDC is working with state health departments to see if there are additional U.S. cases, and what may be causing these cases,” she wrote. “Adenovirus may be the cause for these, but investigators are still learning more—including ruling out the more common causes of hepatitis.” Wes Stubblefield, a district medical officer with the Alabama Department of Public Health, said in an interview today that the most recent case in Alabama occurred in February, and that five of the nine children tested positive for adenovirus-41, a strain that commonly causes gastroenteritis. Meanwhile, in Spain, the government of the Madrid region announced on 13 April that three regions—Madrid, Aragón, and Castilla-La Mancha—had each reported a case of severe hepatitis of unknown origin in young children. One child has received a liver transplant. Physicians at major pediatric liver centers in the Netherlands and Denmark told ScienceInsider yesterday they are seeing similar trends. “There are children that are very sick and have been referred for transplantation,” says Ruben de Kleine, a pediatric liver transplant surgeon at University Medical Center Groningen. “We have assessed a similar number of kids for transplantation within the first 4 months of 2022 [to what we] normally do in a whole year.” At Copenhagen University Hospital, too, “we have more cases with [acute liver failure] than we normally have,” says pediatric hepatologist Marianne Hørby Jørgensen. No children there have needed transplants. Hørby Jørgensen and de Kleine both stress that parents should not panic. To date, clinicians have identified small numbers of cases in their countries where, combined, more than 230,000 infants are born each year.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

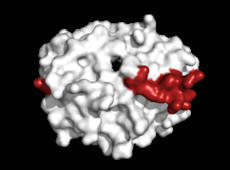

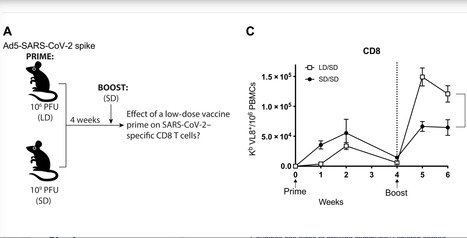

SARS-CoV-2 has caused a global pandemic that has infected more than 250 million people worldwide. Although several vaccine candidates have received emergency use authorization, there is still limited knowledge on how vaccine dosing affects immune responses. We performed mechanistic studies in mice to understand how the priming dose of an adenovirus-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine affects long-term immunity to SARS-CoV-2. We first primed C57BL/6 mice with an adenovirus serotype 5 vaccine encoding the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, similar to that used in the CanSino and Sputnik V vaccines. The vaccine prime was administered at either a standard dose or 1000-fold lower dose, followed by a boost with the standard dose 4 weeks later. Initially, the low dose prime induced lower immune responses relative to the standard dose prime. However, the low dose prime elicited immune responses that were qualitatively superior and, upon boosting, exhibited substantially more potent recall and functional capacity. We also report similar effects with a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) vaccine. These findings show an unexpected advantage of fractionating vaccine prime doses, warranting a reevaluation of vaccine trial protocols for SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens. Published in Science Immunology: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.abi8635

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Agency declines import permit, claiming crippled adenovirus that serves as vaccine is active in second doses. A confusing and unusually nasty fight broke out this week over the safety of a Russian COVID-19 vaccine known as Sputnik V after a Brazilian health agency declined on Monday to authorize its import because of quality and safety concerns. The stakes escalated yesterday when the Twitter account officially associated with the vaccine said “Sputnik V is undertaking a legal defamation proceeding” against Brazil’s regulators. In an online press conference several hours later, the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (Anvisa) defended its decision, maintaining that documentation from some of the Russian facilities making Sputnik V shows that one of its two doses contains adenoviruses capable of replication, a potential danger to vaccine recipients. The vaccine uses two different adenoviruses, which cause the common cold, to deliver the gene for the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVD-19. Both are supposed to be stripped of a key gene that allows them to replicate. The Monday announcement left many scientists and media outlets believing Anvisa had directly tested Sputnik V for replicating adenoviruses, which would be unusual for a regulatory agency. But Anvisa has since clarified—it had not and was relying on information provided by the Gamaleya National Center of Epidemiology and Microbiology, the Moscow-based developer of the vaccine. “The data we evaluated shows the presence of replicating virus,” Gustavo Mendes, general manager of medicines and biological products at Anvisa, said at the press conference. Anvisa would not accept the vaccine, he said, without further studies to indicate it is safe. Gamaleya said in a statement on its website that Anvisa’s allegations “have no scientific grounds and cannot be treated seriously.” The research institute added that “no replication-competent adenoviruses (RCA) were ever found in any of the Sputnik V vaccine batches” and said a four-stage purification process prevents contamination. The furor comes as Brazil, which has one of the highest burdens of COVID-19 in the world, is desperately trying to expand its vaccination campaign. The country has vaccinated just 14% of its people with a first dose and governors from some states hoped to bolster that effort by grouping together to buy 30 million doses of Sputnik V. The spat has bewildered and divided outsider observers, in Brazil and elsewhere. Some scientists have used social media to decry the apparent contamination and some have denounced the aggressive response by Sputnik V’s backers, who were already under fire for releasing little data on the vaccine’s safety record. On Wednesday, an agency of the European Union also issued a report criticizing Russia’s promotional effort for Sputnik V for providing disinformation. Other scientists, however, have questioned whether Anvisa appropriately interpreted the information provided by Sputnik V’s makers, and whether the media has too readily accepted the agency’s claim that the vaccine is contaminated. The stakes are high because Sputnik V has been authorized for use in more than 60 countries, although neither the World Health Organization nor the European Medicines Agency has yet authorized it. “We need this vaccine. It’s cheap. It’s effective. It’s easy to store and transport,” says Hildegund Ertl, an adenovirus vaccine scientist at the Wistar Institute. “If the press could just take a deep breath before they rush to conclusions it would really help us all.” One of the scientists who criticized Sputnik V this week on Twitter said she is keeping an open mind. “I will be glad to correct myself in public should the data be shared,” says Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan. (Her Twitter thread about Anvisa’s decision got a response from Sputnik V’s account that read “please do not spread fake news.”) Viruses reborn? The Anvisa review of Sputnik V was triggered because the Brazilian governors needed the agency’s sign-off to import the vaccine. Although complaints about Russia’s lack of transparency with Sputnik V data have simmered for months, many public health officials and scientists worldwide had been reassured when The Lancet recently published results from nearly 20,000 people in a clinical trial. The study showed the vaccine was safe and had an efficacy of 91.6% at preventing symptomatic COVID-19. Both of the adenoviruses that make up Sputnik V, known as Ad5 and Ad26, are churned out by cultured human cells called HEK293 cells. The adenoviruses ferry the coronavirus spike gene to the vaccine recipient’s cells, which then make spike, prompting an immune response. In order to stop the adenoviruses from replicating once inside their human host, the vaccinemaker removed a gene they need for reproduction, called E1. The viruses can copy themselves in HEK293 cells, which are engineered to have a stand-in E1 gene, but they are not supposed to be able to replicate once they are separated from the human cells and packaged in the final vaccine product. It’s long been known that Ad5 can on rare occasions acquire the E1 gene from the HEK293 cells, converting what is supposed to be a crippled virus into an RCA. Although adenoviruses typically cause mild colds, they can rarely kill people, and immunocompromised people who receive a vaccine that inadvertently contains RCAs could be at particular risk. Vaccine makers and others have developed tests to check for replicating adenoviruses in their products. Anvisa said that although the standard worldwide has been zero tolerance for the presence of replicating adenovirus in the vaccine, Gamaleya established an acceptable limit of 5000 replication-capable virus particles per vaccine dose. The Russian quality control documents displayed by Anvisa during the press conference state the batches tested had “less than 100” replication-capable particles per dose. During yesterday’s press conference, Mendes also showed video of parts of an online meeting in March between officials from Anvisa and the vaccine’s developer. In one of the clips, Anvisa officials ask Gamaleya representatives why they had not changed their production methods once they “had detected the RCA occurrence in your production” The Gamaleya representatives responded that they were aware of the risk, but that changing the process “would take too much time.” Mendes noted that Anvisa has analyzed the quality control documentation on other adenovirus-based COVID-19 vaccines, such as those made by AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson, and found no evidence of replication-competent viruses in those companies’ final products..... Published in Science (April 30, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj2483

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

We are writing to express concern about the use of a recombinant adenovirus type-5 (Ad5) vector for a COVID-19 phase 1 vaccine study,1 and subsequent advanced trials. Over a decade ago, we completed the Step and Phambili phase 2b studies that evaluate an Ad5 vectored HIV-1 vaccine administered in three immunisations for efficacy against HIV-1 acquisition. Both international studies found an increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition among vaccinated men. The Step trial found that men who were Ad5 seropositive and uncircumcised on entry into the trial were at elevated risk of HIV-1 acquisition during the first 18 months of follow-up. The hazard ratios were particularly high among men who were uncircumcised and Ad5 seropositive, and who reported unprotected insertive anal sex with a partner who was HIV-1 seropositive or had unknown serostatus at baseline, suggesting the potential for increased risk of penile acquisition of HIV-1. Importantly for considering the potential use of Ad5 vectors for COVID-19 infection, a similar increased risk of HIV infection was also observed in heterosexual men who enrolled in the Phambili study. This effect appeared to persist over time. Both studies involved an Ad5 construct that did not have the HIV-1 envelope. In another HIV study, done only in men who were Ad5 seronegative and circumcised, a DNA prime followed by an Ad5 vector were used, in which both constructs contained the HIV-1 envelope. No increased risk of HIV infection was noted. A consensus conference about Ad5 vectors held in 2013 and sponsored by the National Institutes of Health indicated the most probable explanation for these differences related to the potential counterbalancing effects of envelope immune responses in mitigating the effects of the Ad5 vector on HIV-1 acquisition. The conclusion of this consensus conference warned that non-HIV vaccine trials that used similar vectors in areas of high HIV prevalence could lead to an increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition in the vaccinated population. The increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition appeared to be limited to men; a similar increase in risk was not seen in women in the Phambili trial... Published in The Lancet (October 19, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32156-5

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Nasal delivery produces more widespread immune response than intramuscular injection. Scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a vaccine that targets the SARS-CoV-2 virus, can be given in one dose via the nose and is effective in preventing infection in mice susceptible to the novel coronavirus. The investigators next plan to test the vaccine in nonhuman primates and humans to see if it is safe and effective in preventing COVID-19 infection. The study is available online in the journal Cell. Unlike other COVID-19 vaccines in development, this one is delivered via the nose, often the initial site of infection. In the new study, the researchers found that the nasal delivery route created a strong immune response throughout the body, but it was particularly effective in the nose and respiratory tract, preventing the infection from taking hold in the body. “We were happily surprised to see a strong immune response in the cells of the inner lining of the nose and upper airway — and a profound protection from infection with this virus,” said senior author Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine and a professor of molecular microbiology, and of pathology and immunology. “These mice were well protected from disease. And in some of the mice, we saw evidence of sterilizing immunity, where there is no sign of infection whatsoever after the mouse is challenged with the virus.” To develop the vaccine, the researchers inserted the virus’ spike protein, which coronavirus uses to invade cells, inside another virus – called an adenovirus – that causes the common cold. But the scientists tweaked the adenovirus, rendering it unable to cause illness. The harmless adenovirus carries the spike protein into the nose, enabling the body to mount an immune defense against the SARS-CoV-2 virus without becoming sick. In another innovation beyond nasal delivery, the new vaccine incorporates two mutations into the spike protein that stabilize it in a specific shape that is most conducive to forming antibodies against it. “Adenoviruses are the basis for many investigational vaccines for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, such as Ebola virus and tuberculosis, and they have good safety and efficacy records, but not much research has been done with nasal delivery of these vaccines,” said co-senior author David T. Curiel, MD, PhD, the Distinguished Professor of Radiation Oncology. “All of the other adenovirus vaccines in development for COVID-19 are delivered by injection into the arm or thigh muscle. The nose is a novel route, so our results are surprising and promising. It’s also important that a single dose produced such a robust immune response. Vaccines that require two doses for full protection are less effective because some people, for various reasons, never receive the second dose.” Although there is an influenza vaccine called FluMist that is delivered through the nose, it uses a weakened form of the live influenza virus and can’t be administered to certain groups, including those whose immune systems are compromised by illnesses such as cancer, HIV and diabetes. In contrast, the new COVID-19 intranasal vaccine in this study does not use a live virus capable of replication, presumably making it safer. The researchers compared this vaccine administered to the mice in two ways — in the nose and through intramuscular injection. While the injection induced an immune response that prevented pneumonia, it did not prevent infection in the nose and lungs. Such a vaccine might reduce the severity of COVID-19, but it would not totally block infection or prevent infected individuals from spreading the virus. In contrast, the nasal delivery route prevented infection in both the upper and lower respiratory tract — the nose and lungs — suggesting that vaccinated individuals would not spread the virus or develop infections elsewhere in the body. The researchers said the study is promising but cautioned that the vaccine so far has only been studied in mice. “We will soon begin a study to test this intranasal vaccine in nonhuman primates with a plan to move into human clinical trials as quickly as we can,” Diamond said. “We’re optimistic, but this needs to continue going through the proper evaluation pipelines. In these mouse models, the vaccine is highly protective. We’re looking forward to beginning the next round of studies and ultimately testing it in people to see if we can induce the type of protective immunity that we think not only will prevent infection but also curb pandemic transmission of this virus.” Study Published in Cell (August 19, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.026

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|