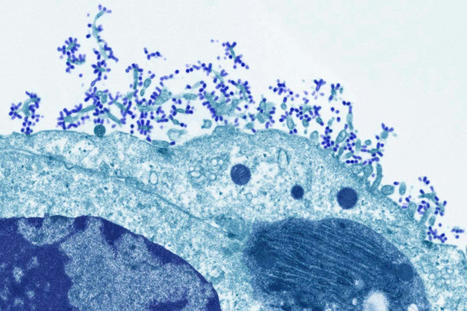

Bird flu has spread widely among animals. Unless we act now, it soon could do the same among humans. As the world is just beginning to recover from the devastation of Covid-19, it is facing the possibility of a pandemic of a far more deadly pathogen. Bird flu — known more formally as avian influenza — has long hovered on the horizons of scientists’ fears. This pathogen, especially the H5N1 strain, hasn’t often infected humans, but when it has, 56 percent of those known to have contracted it have died. Its inability to spread easily, if at all, from one person to another has kept it from causing a pandemic. But things are changing. The virus, which has long caused outbreaks among poultry, is infecting more and more migratory birds, allowing it to spread more widely, even to various mammals, raising the risk that a new variant could spread to and among people. Alarmingly, it was recently reported that a mutant H5N1 strain was not only infecting minks at a fur farm in Spain but also most likely spreading among them, unprecedented among mammals. Even worse, the mink’s upper respiratory tract is exceptionally well suited to act as a conduit to humans, Thomas Peacock, a virologist who has studied avian influenza, told me. The world needs to act now, before H5N1 has any chance of becoming a devastating pandemic. We have many of the tools that are needed, including vaccines. What’s missing is a sense of urgency and immediate action. The best defense against a new deadly pathogen is aggressively suppressing early outbreaks, which first requires detecting them quickly. The United States, the World Health Organization and global health officials already have influenza surveillance networks, but many avian influenza experts told me they don’t think the networks are functioning well enough given the threat level. Such surveillance would need to prioritize people in the poultry industry but also expand beyond that. Thijs Kuiken, an expert in avian influenza at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, says farms for pigs — another species susceptible to influenza — should also be surveilled for bird flu. People interacting with wild birds and animals, as well as susceptible species of pets like ferrets, are also at higher risk. It’s not enough to detect, though: Suppression would require a major effort and global coordination. Unfortunately, mink farms must be shut down — even if it means killing the minks. They are typically killed anyway for their fur at about 6 months of age. It’s hard to imagine a better way to incubate and spread a deadly virus than letting it evolve among tens of thousands of animals with an upper respiratory tract similar to ours crowded together. When the coronavirus infected Danish mink farms in 2020 and the minks generated new variants that then infected humans, the efforts to save the industry were futile because the outbreaks were uncontrollable.

If different strains of flu have infected the same person simultaneously, the strains can swap gene segments and give rise to new, more transmissible ones. If a mink farmworker with the flu also gets infected by H5N1, that may be all it takes to ignite a pandemic. To avoid this, quick testing should be widely available and easy to obtain globally, especially for poultry workers and people handling wild birds or other wildlife. And current testing capabilities should be quickly expanded. There are 91 public health labs in the United States that can test for H5 influenza. Positive results are sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where further analyses can detect H5N1 within about 48 hours. But plans should be in place to increase the amount of tests and testing facilities in case demand ramps up. Perhaps the best news is that we have several H5N1 vaccines already approved by the Food and Drug Administration whose safety and immune response have been studied. The U.S. government has a small H5N1 vaccine stockpile, but it would be nowhere near enough if a serious outbreak occurred. The current plan is to mass-produce them if and when such an outbreak occurs, based on the particular variant involved. There are several problems, though, with this approach even under the best-case scenarios. Producing hundreds of millions of doses of a new vaccine could take six months or more. Worryingly, all but one of the approved vaccines are produced by incubating each dose in an egg. The U.S. government keeps hundreds of thousands of chickens in secret farms with bodyguards. (It’s true!) But the bodyguards are presumably there to fend off terror attacks, not a virus. Relying on chickens to produce vaccines against a virus that has a 90 percent to 100 percent fatality rate among poultry has the makings of the most unfunny which-came-first, the-chicken-or-the-egg riddle. The only company with an F.D.A.-approved non-egg-based H5N1 vaccine expects to be able to produce 150 million doses within six months of the declaration of a pandemic. But there are seven billion people in the world. The mRNA-based platforms used to make two of the Covid vaccines also don’t depend on eggs. Scott Hensley, an influenza expert at the University of Pennsylvania, told me that those vaccines can be mass-produced faster, in as little as three months. There are currently no approved mRNA vaccines for influenza, but efforts to make one should be expedited. If the W.H.O. is to take the lead in expanding global vaccine manufacturing, it needs the support of wealthy countries and the cooperation of large pharmaceutical companies that have the patents and know-how. A big challenge to stockpiling flu vaccines is that they can lose potency over time and need updating as new variants arise. The U.S. government is skeptical about creating a large stockpile, fearing that stored vaccines may not be effective against whatever strain became pandemic, and worries that stockpiles will expire anyway. Officials also have faith that they can get new flu vaccines mass-produced rapidly.

Many influenza experts told me that older vaccines could still provide some protection against severe outcomes or death. Peter Palese, a professor of microbiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who established the first genetic maps for influenza A, B and C viruses, told me that such stockpiles would be especially useful for essential workers. In 2017, the C.D.C. found that the H5N1 vaccine made in 2004 and 2005 helped protect ferrets against an H5N2 virus in 2014. Investigations in 2006 showed that 80 percent of the U.S. stockpile of earlier H5N1vaccines were still potent a full year after their expected one-year shelf life had passed. In 2019, another study found that H5N1 vaccines produced as early as 2004 were still potent a full 12 years later. We could also allow voluntary vaccination, especially for high-risk groups like poultry workers and health care workers, who would be treating patients should outbreaks occur. Voluntary vaccination could also produce larger-scale data on the safety and dosing specifics of vaccines. Vaccinating poultry workers has the additional big benefit of helping suppress outbreaks in the first place. Several influenza experts I spoke to bemoaned the lack of more widespread vaccination for chickens and turkeys. Had all poultry been vaccinated earlier, perhaps H5N1 would have never spread so widely to wild birds. It’s late, but mass vaccination of poultry and pigs should begin quickly. Even getting more people vaccinated — especially poultry and pig farmworkers — against the regular influenza can help. With less regular flu in the world, there would be fewer hosts for an H5N1 virus to co-infect, a process that can lead to strains of H5N1 that can spread more easily.

We already have antivirals for influenza, which work regardless of strain, but they need to be administered early, which requires widespread early testing, easy access, and sufficient and equitable stockpiles globally. Scientists are working toward a universal flu vaccine, potentially covering all variants as well as future pandemic ones — a moonshot, perhaps, but worth the investment.

The pace of developments has been disquieting. Until 2020, when the new H5N1 strain began to spread extensively among wild birds, most big outbreaks occurred among poultry. But now, with wild birds acting as conduits, it’s not just the biggest outbreak ever among poultry, causing the death of at least 150 million animals so far, but it is also steadily expanding its reach, including to mammal species like dolphins and bears. In 2006, when scientists discovered that H5N1 had not spread easily among humans because it settles deep in their lungs, Kuiken of Erasmus University Medical Center warned that if the virus evolved to bind to receptors in the upper respiratory tract — from which it could become more easily airborne — the risk of a pandemic among humans would rise substantially. The mink outbreak in Spain is a signal that we might be moving along exactly that path.

It’s hard to imagine clearer and more alarming warning signs of a potentially horrific pandemic. The public, of course, doesn’t want to hear about another virus, and Congress isn’t even willing to keep funding efforts against the current one. We could get lucky — we’ve had bird flu outbreaks before without human spread. But it seems foolish to count on that. A pandemic strain may have a much lower fatality rate than the 56 percent of known human cases so far, but it still could be much more deadly than the coronavirus, which is estimated to have killed 1 percent to 2 percent of those infected before vaccines or treatments were available. Deadly influenza pandemics occur regularly in human history, and they don’t wait until people recover from an earlier outbreak, no matter how weary we may all feel. This time, we have not just the warning, but also many of the tools we need to fend a pandemic off. We should not wait until it’s too late.

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...