Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

This is a technical summary of an analysis of the genomic sequence of the virus identified in the Michigan case of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) virus infection. This analysis supports the conclusion that the overall risk to the general public associated with the ongoing HPAI A(H5N1) outbreak has not changed and remains low at this time. The genome of the virus identified from the patient in Michigan (A/Michigan/90/2024) is publicly posted in GISAID (EPI_ISL_19162802) and has been submitted to GenBank (PP839258-PP839265) May 24, 2024 – CDC has sequenced the influenza virus genome identified in a conjunctival specimen collected from the person in Michigan who was identified to be infected with HPAI A(H5N1) virus and compared each gene segment with HPAI A(H5N1) sequences from cows, wild birds and poultry and the first human case in Texas. The virus HA was identified as clade 2.3.4.4b with each individual gene segment closely related to genotype B3.13 viruses detected in dairy cows available from USDA testing. No amino acid changes were identified in the HA gene sequence from the Michigan patient specimen compared to the HA sequence from the case in Texas and only minor changes were identified when compared to sequences from cows. These data indicate viruses detected in both cows and the two human cases maintain primarily avian genetic characteristics and lack changes that would make them better adapted to infect or transmit between humans. The genome of the human virus from Michigan did not have the PB2 E627K change detected in the virus from the Texas case, but had one notable change (PB2 M631L) compared to the Texas case that is known to be associated with viral adaptation to mammalian hosts, and which has been detected in 99% of dairy cow sequences but only sporadically in birds[i]. This change has been identified as resulting in enhancement of virus replication and disease severity in mice during studies with avian influenza A(H10N7) viruses[ii]. The remainder of the genome of A/Michigan/90/2024 was closely related to sequences detected in infected dairy cows and strongly suggests direct cow-to-human transmission. Further, there are no markers known to be associated with influenza antiviral resistance found in the virus sequences from the Michigan specimen and the virus is very closely related to two existing HPAI A(H5N1) candidate vaccine viruses that are already available to manufacturers, and which could be used to make vaccine if needed. Overall, the genetic analysis of the HPAI A(H5N1) virus detected in a human in Michigan supports CDC’s conclusion that the human health risk currently remains low. More details of this and other viruses characterized in association with the dairy cow outbreak are available in a previous technical summary.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Infections with the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b virus have resulted in the death of millions of domestic birds and thousands of wild birds in the U.S. since January, 2022. Throughout this outbreak, spillovers of the virus to mammals have been frequently documented. Here, we report the detection of HPAI H5N1 virus in dairy cattle herds across several states in the U.S. The affected cows displayed clinical signs encompassing decreased feed intake, altered fecal consistency, respiratory distress, and decreased milk production with abnormal milk. Infectious virus and RNA were consistently detected in milk collected from affected cows. Viral staining in tissues revealed a distinct tropism of the virus for the epithelial cells lining the alveoli of the mammary gland in cows. Analysis of whole genome sequences obtained from dairy cows, birds, domestic cats, and a racoon from affected farms indicated multidirectional interspecies transmissions. Epidemiologic and genomic data revealed efficient cow-to-cow transmission after healthy cows from an affected farm were transported to a premise in a different state. These results demonstrate the transmission of HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b virus at a non-traditional interface and to a new and highly relevant livestock species, underscoring the ability of the virus to cross species barriers. Available in bioRxiv (May 22, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.22.595317

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The infection was detected in a farm worker who had been exposed to cows infected with the H5N1 virus, Michigan health officials said. A second human case of bird flu infection linked to the current H5N1 outbreak in dairy cows has been detected, in a farm worker who had exposure to infected cows, Michigan state health authorities announced on Wednesday. In a statement, health officials said the individual had mild symptoms and has recovered. Evidence to date suggests this is a sporadic infection, with no signs of ongoing spread, the statement said....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Outbreaks of highly pathogenic H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b viruses in farmed mink and seals combined with isolated human infections suggest these viruses pose a pandemic threat. To assess this threat, using the ferret model, we show an H5N1 isolate derived from mink transmits by direct contact to 75% of exposed ferrets and, in airborne transmission studies, the virus transmits to 37.5% of contacts. Sequence analyses show no mutations were associated with transmission. The H5N1 virus also has a low infectious dose and remains virulent at low doses. This isolate carries the adaptive mutation, PB2 T271A, and reversing this mutation reduces mortality and airborne transmission. This is the first report of a H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b virus exhibiting direct contact and airborne transmissibility in ferrets. These data indicate heightened pandemic potential of the panzootic H5N1 viruses and emphasize the need for continued efforts to control outbreaks and monitor viral evolution. In 2023, a highly pathogenic H5N1 virus caused an outbreak in mink. In the ferret model of influenza, the virus exhibits limited airborne transmissibility and high virulence. These findings indicate heightened pandemic potential of these viruses. Published in Nature Comm. (May 15, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48475-y

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Federal public health officials are turning to wastewater surveillance to help fill in the gaps in efforts to track H5N1 bird flu outbreaks in dairy cows. R eluctance among dairy farmers to report H5N1 bird flu outbreaks within their herds or allow testing of their workers has made it difficult to keep up with the virus’s rapid spread, prompting federal public health officials to look to wastewater to help fill in the gaps. On Tuesday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is expected to unveil a public dashboard tracking influenza A viruses in sewage that the agency has been collecting from 600 wastewater treatment sites around the country since last fall. The testing is not H5N1-specific; H5N1 belongs to the large influenza A family of viruses, as do two of the viruses that regularly sicken people during flu season. But flu viruses that cause human disease circulate at very low levels during the summer months. So the presence of high levels of influenza A in wastewater from now through the end of the summer could be a reliable indicator that something unusual is going on in a particular area. Wastewater monitoring, at least at this stage, cannot discern the sources — be they from dairy cattle, run-off from dairy processors, or human infections — of any viral genetic fragments found in sewage, although the agency is working on having more capability to do so in the future. CDC wastewater team lead Amy Kirby told STAT that starting around late March or early April, some wastewater collection sites started to notice unusual increases in influenza A virus in their samplings. Those readings stood out because by the last week of March, data the CDC tracks on the percentage of people seeking medical care for influenza-like illnesses suggested that the 2023-2024 flu season was effectively over. The increases were very site-specific, she said, and were not reflected in other areas. In fact, she called it “a very limited phenomenon. … The vast majority of our sites are not seeing this.” To date there has been little information in the public sphere about where infected cattle herds have been located. When the U.S. Department of Agriculture announces positive test results, it merely names the state in which the herd was located when the testing took place. Last week, the USDA reported that six additional herds — in Michigan, Idaho, and Colorado — had tested positive for H5N1, bringing the total to 42....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

An outbreak of H5N1 highly pathogenic influenza A virus (HPIAV) has been detected in dairy cows in the United States. Influenza A virus (IAV) is a negative-sense, single-stranded, RNA virus that has not previously been associated with widespread infection in cattle. As such, cattle are an extremely under-studied domestic IAV host species. IAV receptors on host cells are sialic acids (SAs) that are bound to galactose in either an α2,3 or α2,6 linkage. Human IAVs preferentially bind SA-α2,6 (human receptor), whereas avian IAVs have a preference for α2,3 (avian receptor). The avian receptor can further be divided into two receptors: IAVs isolated from chickens generally bind more tightly to SA-α2,3-Gal-β1,4 (chicken receptor), whereas IAVs isolated from duck to SA-α2,3-Gal-β1,3 (duck receptor). We found all receptors were expressed, to a different degree, in the mammary gland, respiratory tract, and cerebrum of beef and/or dairy cattle. The duck and human IAV receptors were widely expressed in the bovine mammary gland, whereas the chicken receptor dominated the respiratory tract. In general, only a low expression of IAV receptors was observed in the neurons of the cerebrum. These results provide a mechanistic rationale for the high levels of H5N1 virus reported in infected bovine milk and show cattle have the potential to act as a mixing vessel for novel IAV generation. Preprint in bioRxiv (May 3, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.03.592326

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses cross species barriers and have the potential to cause pandemics. In North America, HPAI A(H5N1) viruses related to the goose/Guangdong 2.3.4.4b hemagglutinin phylogenetic clade have infected wild birds, poultry, and mammals. Our genomic analysis and epidemiological investigation showed that a reassortment event in wild bird populations preceded a single wild bird-to-cattle transmission episode. The movement of asymptomatic cattle has likely played a role in the spread of HPAI within the United States dairy herd. Some molecular markers in virus populations were detected at low frequency that may lead to changes in transmission efficiency and phenotype after evolution in dairy cattle. Continued transmission of H5N1 HPAI within dairy cattle increases the risk for infection and subsequent spread of the virus to human populations. Preprint in bioRxiv (May 01, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.01.591751

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

We report highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in dairy cattle and cats in Kansas and Texas, United States, which reflects the continued spread of clade 2.3.4.4b viruses that entered the country in late 2021. Infected cattle experienced nonspecific illness, reduced feed intake and rumination, and an abrupt drop in milk production, but fatal systemic influenza infection developed in domestic cats fed raw (unpasteurized) colostrum and milk from affected cows. Cow-to-cow transmission appears to have occurred because infections were observed in cattle on Michigan, Idaho, and Ohio farms where avian influenza virus–infected cows were transported. Although the US Food and Drug Administration has indicated the commercial milk supply remains safe, the detection of influenza virus in unpasteurized bovine milk is a concern because of potential cross-species transmission. Continued surveillance of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in domestic production animals is needed to prevent cross-species and mammal-to-mammal transmission. Published in Emerging Infectious Diseases (April 20, 2024) https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3007.240508

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Bird flu isn’t just lurking inside cows, new research shows. Florida scientists have reported the first known case of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza in a common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). Though the case dates back to 2022, it’s the latest indication that these flu strains can potentially infect a wide variety of mammals. The report was published Friday in the Nature journal Communications Biology. According to the paper, the flu-infected dolphin was first identified on March 29, 2022. Researchers with the University of Florida’s Marine Animal Rescue Program were notified of a dolphin that appeared to be in clear distress around the waters of Horseshoe Beach in North Florida. By the time they arrived, however, the dolphin had already died. It was subsequently packed in ice and taken to the university for an autopsy the following day. The post-mortem examination found signs of poor health and inflammation in the dolphin’s brain and meninges (the membrane layers that protect the brain and spinal cord). The dolphin tested negative for other common infectious causes of brain inflammation, which prompted the researchers to expand their search. They knew that wild birds can develop neuroinflammation from highly pathogenic strains of avian influenza, that several bird die-offs tied to the flu had occurred in the area recently, and that recent outbreaks had occurred among other populations of marine mammals elsewhere, so they decided to screen for it. Testing then revealed the presence of H5N1 within the dolphin’s lungs and brain. There have been sightings of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in other marine mammals lately, such as harbor seals and other species of dolphins. But this is the first reported case documented in a common bottlenose dolphin and the first report in any cetacean (dolphins and whales) within the waters of North America. Strains of bird flu are classified as highly pathogenic when they cause severe illness and deaths in wild birds, so it’s not necessarily a given that they will be as dangerous to other animals they infect. The current outbreaks of H5N1 bird flu in cows, for instance, have caused generally mild illness to date. But strains belonging to this particular lineage of H5N1 (2.3.4.4b) have been deadly to marine mammals. The strain in this case did not appear to develop known genetic changes that would make it easier to infect and transmit between mammals, the authors found. But flu viruses mutate very quickly, leaving open the possibility that some strains will adapt and pick up the right changes that can make them a much bigger threat to mammals both on land and in the sea. “Human health risk aside, the consequences of A(H5N1) viruses adapting for enhanced replication in and transmission between dolphins and other cetacea could be catastrophic for these populations,” the authors wrote. The researchers are continuing to investigate the case, hoping to pinpoint the origins of the dolphin’s infection and to better understand the potential for bird flu strains to successfully jump the species barrier to these marine mammals. Studiy cited published in Communications Biology (April 18, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06173-x

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

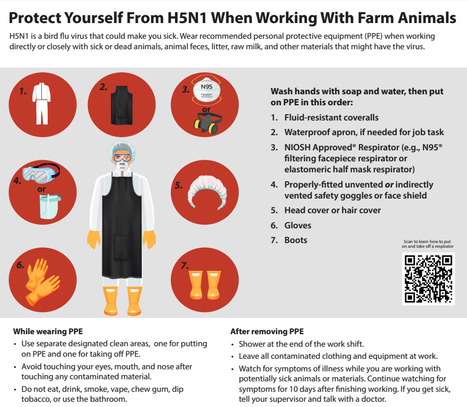

Recommendations for Worker Protection and Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to Reduce Exposure to Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A H5 Viruses - CDC Information for workers Any person working with or exposed to animals such as poultry and livestock farmers and workers, backyard bird flock owners, veterinarians and veterinary staff, and responders should take steps to reduce the risk of infection with avian influenza A viruses associated with severe disease when working with animals or materials potentially infected or confirmed to be infected with these viruses. Avoid unprotected direct or close physical contact with: - Sick birds, livestock, or other animals

- Carcasses of birds, livestock, or other animals

- Feces or litter

- Raw milk

- Surfaces and water (e.g., ponds, waterers, buckets, pans, troughs) that might be contaminated with animal excretions.

If you must work with or enter any not yet disinfected buildings where these materials or sick or dead animals potentially infected or confirmed to be infected are or were present, wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) in addition to the PPE you might be using for your normal duties (e.g., waterproof apron, hearing protection, etc.). Appropriate PPE depends on the hazards present and a site-specific risk assessment. If you have questions on the type of PPE to use or how to fit it properly, ask your supervisor. Recommended PPE to protect against novel influenza A viruses includes: - Disposable or non-disposable fluid-resistant [i] coveralls, and depending on task(s), add disposable or non-disposable waterproof apron

- Any NIOSH Approved® particulate respirator (e.g., N95® or greater filtering facepiece respirator, elastomeric half mask respirator with a minimum of N95 filters)

- Properly-fitted unvented or indirectly vented safety goggles [ii] or a faceshield if there is risk of liquid splashing onto the respirator

- Rubber boots or rubber boot covers with sealed seams that can be sanitized or disposable boot covers for tasks taking a short amount of time

- Disposable or non-disposable head cover or hair cover

- Disposable or non-disposable gloves [iii]

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The U.S. must act decisively, acknowledging the potential gravity of H5N1 mammalian transmission. Humans have no natural immunity to the bird flu virus. The recent detection of H5N1 bird flu in U.S. cattle, coupled with reports of a dairy worker contracting the virus, demands a departure from the usual reassurances offered by federal health officials. While they emphasize there’s no cause for alarm and assert diligent monitoring, it’s imperative we break from this familiar script. H5N1, a strain of the flu virus known to infect bird species globally and several mammalian species in the U.S. since 2022, has now appeared to have breached a new barrier of inter-mammalian transmission, as exemplified by the expanding outbreak in dairy cows in several jurisdictions linked to an initial outbreak in Texas. Over time, continued transmission among cattle is likely to yield mutations that will further increase the efficiency of mammal-to-mammal transmission. As the Centers for Disease Control continues to investigate, this evolutionary leap, if confirmed, underscores the adaptability of the H5N1 virus and raises concerns about the next step required for a pandemic: its potential to further evolve for efficient human transmission. Because humans have no natural immunity to H5N1, the virus can be particularly lethal to them. Despite assertions of an overall low risk of H5N1 infection to the general population, the reality is that the understanding of this risk is limited, and it’s evolving alongside the virus. The situation could change very quickly, so it is important to be prepared. Comparisons to seasonal flu management underestimate the unique challenges posed by H5N1. Unlike its seasonal counterparts, vaccines produced and stockpiled to tackle bird flu were not designed to match this particular strain and are available in such limited quantities that they could not make a dent in averting or mitigating a pandemic, even if deployed in the early stages to dairy workers. The FDA-approved H5N1 vaccines — licensed in 2013, 2017, and 2020 — do not elicit a protective immune response after just one dose. Even after two doses, it is unknown whether the elicited immune response is sufficient to protect against infection or severe disease, as these vaccines were licensed based on their ability to generate an immune response thought to be helpful in preventing the flu. Early studies done by mRNA vaccine companies on seasonal flu are promising, which could be good news here since mRNA vaccines can be made more quickly than vaccines using eggs or cells. Congressional funding is needed to catalyze rapid vaccine development and production. While FDA-approved antiviral drugs like Tamiflu and Xofluza could be an important line of defense against H5N1, logistical barriers impede their timely administration, as they work best when given as early as possible within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms. Most Americans would find it challenging to get a prescription filled for these medicines within the optimal time frame. Streamlining access to stockpiled antiviral drugs through improved test-to-treat measures like behind-the-counter distribution or dedicated telemedicine consultations could vastly improve their effectiveness as a frontline defense. Making plans to do that need to start now. For vulnerable people — older adults and anyone who is immunocompromised — clinicians have become accustomed to relying on monoclonal antibodies. Sadly, their performance for flu has been disappointing in many clinical trials and can’t be counted on. The need for robust diagnostic capabilities cannot be overstated. H5N1 will not be detected by the typical rapid flu antigen tests that are administered in emergency rooms and many doctors’ offices. New tests will have to be made from scratch. The dismantling of diagnostic infrastructure post-Covid-19 and supply chain disruptions, however, pose significant challenges to the availability of such tests. Rapid investment in diagnostic testing, coupled with efforts to secure essential materials, is imperative to ensure timely detection and antiviral treatment. President Biden’s emphasis on infrastructure presents a unique opportunity to fortify America’s defenses against infectious diseases. A national initiative to enhance indoor air quality in schools and communal spaces could mitigate transmission risks should this virus learn how to efficiently be transmitted between humans, and would pay dividends every respiratory virus season and for years to come. In the face of uncertainty, complacency is not an option. The U.S. must act decisively, acknowledging the potential gravity of the H5N1 situation while leveraging every available resource to safeguard public health. The stakes are too high to repeat past mistakes. Luciana Borio is an infectious disease physician, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations, a venture partner at ARCH Venture Partners, and former director for medical and biodefense preparedness policy at the National Security Council. Phil Krause is a virologist, infectious disease physician, and former deputy director of the Office of Vaccines Research and Review at the FDA. The authors have no links to any companies producing or evaluating any of the vaccines or therapies mentioned in this article, and declare no conflicts of interest.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Health Alert Network (HAN). Provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Summary The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is issuing this Health Alert Network (HAN) Health Advisory to inform clinicians, state health departments, and the public of a recently confirmed human infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) virus in the United States following exposure to presumably infected dairy cattle. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) recently reported detections of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in U.S. dairy cattle in multiple states. This Health Advisory also includes a summary of interim CDC recommendations for preventing, monitoring, and conducting public health investigations of potential human infections with HPAI A(H5N1) virus. Background

A farm worker on a commercial dairy farm in Texas developed conjunctivitis on approximately March 27, 2024, and subsequently tested positive for HPAI A(H5N1) virus infection. HPAI A(H5N1) viruses have been reported in the area’s dairy cattle and wild birds. There have been no previous reports of the spread of HPAI viruses from cows to humans. The patient reported conjunctivitis with no other symptoms, was not hospitalized, and is recovering. The patient was recommended to isolate and received antiviral treatment with oseltamivir. Illness has not been identified in the patient’s household members, who received oseltamivir for post-exposure prophylaxis per CDC Recommendations for Influenza Antiviral Treatment and Chemoprophylaxis. No additional cases of human infection with HPAI A(H5N1) virus associated with the current infections in dairy cattle and birds in the United States, and no human-to-human transmission of HPAI A(H5N1) virus have been identified.

CDC has sequenced the influenza virus genome identified in a specimen collected from the patient and compared it with HPAI A(H5N1) sequences from cattle, wild birds, and poultry. While minor changes were identified in the virus sequence from the patient specimen compared to the viral sequences from cattle, both cattle and human sequences lack changes that would make them better adapted to infect mammals. In addition, there were no markers known to be associated with influenza antiviral drug resistance found in the virus sequences from the patient’s specimen, and the virus is closely related to two existing HPAI A(H5N1) candidate vaccine viruses that are already available to manufacturers, and which could be used to make vaccine if needed. This patient is the second person to test positive for HPAI A(H5N1) virus in the United States. The first case was reported in April 2022 in Colorado in a person who had contact with poultry that was presumed to be infected with HPAI A(H5N1) virus. Currently, HPAI A(H5N1) viruses are circulating among wild birds in the United States, with associated outbreaks among poultry and backyard flocks and sporadic infections in mammals....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

U.S. regulators confirmed that sick cattle in Texas, Kansas and possibly in New Mexico contracted avian influenza. They stressed that the nation’s milk supply is safe. A highly fatal form of avian influenza, or bird flu, has been confirmed in U.S. cattle in Texas and Kansas, the Department of Agriculture announced on Monday. It is the first time that cows infected with the virus have been identified. The cows appear to have been infected by wild birds, and dead birds were reported on some farms, the agency said. The results were announced after multiple federal and state agencies began investigating reports of sick cows in Texas, Kansas and New Mexico. In several cases, the virus was detected in unpasteurized samples of milk collected from sick cows. Pasteurization should inactivate the flu virus, experts said, and officials stressed that the milk supply was safe. “At this stage, there is no concern about the safety of the commercial milk supply or that this circumstance poses a risk to consumer health,” the agency said in a statement. Outside experts agreed. “It has only been found in milk that is grossly abnormal,” said Dr. Jim Lowe, a veterinarian and influenza researcher at the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In those cases, the milk was described as thick and syrupy, he said, and was discarded. The agency said that dairies are required to divert or destroy milk from sick animals.... USDA report (March 25, 2024): https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/news/sa_by_date/sa-2024/hpai-cattle

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Mice administered raw milk samples from dairy cows infected with H5N1 influenza experienced high virus levels in their respiratory organs and lower virus levels in other vital organs. Mice administered raw milk samples from dairy cows infected with H5N1 influenza experienced high virus levels in their respiratory organs and lower virus levels in other vital organs, according to findings published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results suggest that consumption of raw milk by animals poses a risk for H5N1 infection and raises questions about its potential risk in humans. Since 2003, H5N1 influenza viruses have circulated in 23 countries, primarily affecting wild birds and poultry with about 900 human cases, primarily among people who have had close contact with infected birds. In the past few years, however, a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus called HPAI H5N1 has spread to infect more than 50 animal species, and in late March, the United States reported a viral outbreak among dairy cows in Texas. To date, 52 cattle herds across nine states have been affected, with two human infections detected in farm workers with conjunctivitis. Although the virus has so far shown no genetic evidence of acquiring the ability to spread from person-to-person, public health officials are closely monitoring the dairy cow situation as part of overarching pandemic preparedness efforts. To assess the risk of H5N1 infection by consuming raw milk, researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory fed droplets of raw milk from infected dairy cattle to five mice. The animals demonstrated signs of illness, including lethargy, on day one and were euthanized on day four to determine organ virus levels. The researchers discovered high levels of virus in the animals’ nasal passages, trachea and lungs and moderate-to-low virus levels in other organs, consistent with H5N1 infections found in other mammals. In addition to the mice studies, the researchers also tested to determine which temperatures and time intervals inactivate H5N1 virus in raw milk from dairy cows. Four milk samples with confirmed high H5N1 levels were tested at 63 degrees Celsius (145.4 degrees Fahrenheit) for 5, 10, 20 and 30 minutes, or at 72 degrees Celsius (161.6 degrees Fahrenheit) for 5, 10, 15, 20 and/or 30 seconds. Each of the time intervals at 63℃ successfully killed the virus. At 72℃, virus levels were diminished but not completely inactivated after 15 and 20 seconds. The authors emphasize, however, that their laboratory study was not identical to large-scale industrial pasteurization of raw milk and reflect experimental conditions that should be replicated with direct measurement of infected milk in commercial pasteurization equipment. In a separate experiment, the researchers stored raw milk infected with H5N1 at 4℃ (39.2 degrees Fahrenheit) for five weeks and found only a small decline in virus levels, suggesting that the virus in raw milk may remain infectious when maintained at refrigerated temperatures. To date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) concludes that the totality of evidence continues to indicate that the commercial milk supply is safe. While laboratory benchtop studies provide important, useful information, there are limitations that challenge inferences to real world commercial processing and pasteurization. The FDA conducted an initial survey of 297 retail dairy products collected at retail locations in 17 states and represented products produced at 132 processing locations in 38 states. All of the samples were found to be negative for viable virus. These results underscore the opportunity to conduct additional studies that closely replicate real world conditions. FDA, in partnership with USDA, is conducting pasteurization validation studies – including the use of a homogenizer and continuous flow pasteurizer. Additional results will be made available as soon as they are available. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, funded the work of the University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers. Published in NEJM (May 25, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2405495

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

How easy is it to switch from seasonal to pandemic flu vaccine production? Does a bird flu vaccine for cows make sense? The answers are complicated. If the H5N1 bird flu virus ever acquires the ability to transmit easily to and among people — keep your fingers crossed that it doesn’t — the world is going to need serious amounts of vaccine. Like, lakes of the stuff. Some manufacturers have been working with H5N1 viruses for years, producing small batches of doses that have undergone preliminary human testing. Some millions of doses — in the low double digits — have even been stockpiled by the U.S. government. But deciding when to start producing H5 vaccine at scale, in the quantities needed to vaccinate the world, is no easy feat. It’s a high-cost, high-risk endeavor. Get it right and you save lives. Hesitate, and lives will be lost. But making the call if the vaccine turns out not to be needed is not a cost-free decision either. There are some obvious questions that come to mind when you start thinking about what might trigger mass production of H5N1 vaccine. Here are a few, and some things to think about to help make sense of a truly complicated situation. Given the concern about H5N1 in dairy cattle, why not just start making H5N1 vax now, in case we need it? The global capacity to make flu vaccine is in the range of about 1.2 billion trivalent (three components in one) doses of vaccine a year, according to a market assessment the World Health Organization published in January. Most of the year, that production capacity is in use doing what it was built to do, making seasonal flu vaccine for the Northern and Southern hemisphere flu seasons. In the weeks between those two runs, plant maintenance is typically done. In a flu pandemic, the output of all those production lines would shift to making pandemic vaccine to protect against the new strain of flu that would likely be triggering large waves of illness worldwide. Here’s the thing. The production lines can make seasonal flu vaccine. Or they can make pandemic flu vaccine. They cannot make both at the same time. That’s why deciding to make pandemic flu vaccine at scale is not a no-cost decision. “You can’t just press the button and begin producing pandemic H5 vaccines. You have to stop producing your seasonal vaccine, and all of you out there know how lifesaving that vaccine is,” Mike Ryan, head of the WHO’s health emergencies program, told reporters at a press conference earlier this month. “So, this requires a very careful consideration.” When decisions like these have to be made, it’s not clear how things are going to play out. A new virus might cause a devastating pandemic. Or, as was the case in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, it might trigger an event that is so mild that politicians will later question whether an emergency response was needed. (In a recent interview, Tom Frieden, who was director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention during the H1N1 pandemic, called it “a pimple of a pandemic.”) In 2009, the world didn’t really have to make a tough decision about whether to stop seasonal flu vaccine production, said Marie-Paule Kieny, who was WHO’s assistant director-general for health systems and innovation at the time. (Kieny has since retired from the global health agency.) That’s because production of the seasonal vaccine for the 2009-2010 Northern Hemisphere winter was almost completed when it became clear the new virus had triggered a pandemic. But another time, a decision might have to be taken to abort the seasonal flu vaccine effort to switch to pandemic vaccine — a decision that would be costly for producers. In most cases, manufacturers only get paid for vaccines they deliver, and if they have to junk a run of seasonal flu vaccine because the client decides it wants pandemic, not seasonal flu vaccine, they have to absorb those costs, said Paula Barbosa, associate director for vaccine policy for the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA). Sure, they’d probably end up selling all the pandemic vaccine doses they could make, as quickly as they could make them. But the costs associated with the abandoned run would eat into those profits. “Individual companies might have specific agreements with certain countries, but overall, what is lost, it’s on the manufacturers,” Barbosa said. There can be opportunity costs as well. At a point during the Covid-19 pandemic, when global vaccine production was operating at full steam, there was a global shortage of glass for vaccine vials. Everything used in vaccine production — the eggs viruses are grown in for most of the traditional flu vaccine manufacturing, the equipment needed to administer vaccines — would likely be in short supply in a serious pandemic. Using any of this stuff to make or administer seasonal vaccine when pandemic vaccine is needed would be a wasted opportunity. “You have to be totally conscious that, especially when you get to a global scale, it’s syringes, it’s needles, vials. It’s the capacity to fill and finish the vaccine. We don’t have that at global scale and most of it, like the antigen, or much of it is concentrated in better-off countries. So yeah, there is a huge supply chain and logistics challenge if we have a global pandemic,” said Jesse Goodman, who was director of the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research during the 2009 pandemic. Goodman is now director of the Center on Medical Product Access, Safety and Stewardship at Georgetown University. Barbosa pointed out another cost of switching into pandemic vaccine production mode. Big manufacturers, like Sanofi and CSL Seqirus, run their flu vaccine production facilities year round, serving clients in both hemispheres. But some smaller companies that make flu vaccine for local markets make it half the year and produce pediatric vaccines the rest of the time. Switching to pandemic flu vaccine production could mean essential childhood vaccines aren’t available for some period of time, Barbosa said. “We really need a process to altogether take that decision and then for there to be a full understanding of what are the consequences, not only for manufacturers, but for worldwide vaccine production,” she said. Is there a process? Is it clear how a decision to make H5N1 vaccine will be made? “Nothing is clear,” said Kieny. After the 2009 pandemic, the WHO held a series of three meetings with industry, regulators, and national authorities to try to figure out whether a framework for making a switch from seasonal to pandemic production could be devised. Industry very much wanted to know they would be issued marching orders. They still do. “Manufacturers themselves cannot be responsible for this decision,” Barbosa said. “Right now there is no formal process to tell all manufacturers to switch from seasonal vaccine production to pandemic production. Industry does need a clear signal to do that switch even fully or partially,” she said. “WHO declaring a pandemic is helpful. But it might not be enough. For instance, if it’s a pandemic, and the pandemic virus causes milder disease … there may not be a need to manufacture a pandemic vaccine at all.” The WHO-led consultations, which were held from 2013 through 2017, did not result in a firm plan for how to do this. It wasn’t clear that anyone wanted to own this decision-making responsibility, Kieny said — “at least until the situation gets really bad.” Gary Grohmann, who used to be the head of immunobiology for Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration — its FDA-equivalent — was involved in those meetings. He suggested individual countries will give manufacturers they purchase from directions, based on the best advice available from their public health agencies, and from the WHO. When it perceives there is a need, the latter will make a recommendation that pandemic flu vaccine production begin, Grohmann said. “That will be only a recommendation. And it would be up to the individual countries to make the decision and then ask their manufacturers … to make their vaccines and to stop production, possibly, of other vaccines,” he said. Major manufacturers, though, sell to multiple clients. What if the country in which the plant is housed wants to start pandemic vaccine production, but another important client wants to proceed with seasonal production, in case the pandemic doesn’t take off? Kieny believes some big national governments may get the ball rolling when they decide it’s time to buy pandemic vaccine. “It depends when the big customers, and especially the U.S., will say, ‘We think that it’s worth putting the money on the table.’ Then everyone will rush and do the same,” she said. “It’s not a question of a switch. It’s a question of a decision. And it’s a financial decision to invest.” That could be particularly true in the wake of the Covid pandemic, when messenger RNA vaccines made their global debut, especially if a flu pandemic were to happen in the near term. A number of the mRNA manufacturers, Pfizer and Moderna among them, have been working on, but have not yet licensed, seasonal flu vaccines. Without a seasonal product line to disrupt, it would be easier for those players to make pandemic vaccine — should they choose to enter the market. But there would need to be the promise of sales. “For vaccine lines that aren’t used for flu now, the decision isn’t to switch, it’s whether to invest and when to start producing,” Kieny said. Wenqing Zhang, head of the WHO’s global influenza program, said after its 2017 consultation with stakeholders, the WHO revisited the whole question of how pandemic influenza vaccine production would be triggered, eventually coming up with a document called the Pandemic Influenza Vaccine Response-Operational Framework. The document, finalized in 2022, has not been published, she said, because some items in it touch on issues that are up for negotiation in the ongoing efforts to update the International Health Regulations. Zhang said the document, which is not available online, acknowledges that manufacturers would need a signal from the WHO that a pandemic may be underway. But the WHO declaration would be about the risk that the virus poses, she said. Whether the document will be published as is or will require revisions will depend on the outcome of the IHR negotiations. So watch this space. Flu vaccine manufacturers just took a component out of the seasonal vaccine, the influenza B/Yamagata virus that disappeared during the Covid-19 pandemic. Why not use that space in the seasonal shot to start protecting people against H5N1? Goodman actually advocates something similar: He’d like to see H5N1 vaccine made in a monovalent shot — in other words, not combined with vaccines targeting seasonal flu viruses — that people could opt to get if they wanted to start protecting themselves against this virus. He proposed it in an article in Clinical Infectious Diseases in 2016. Rather than stockpile vaccine against H5, stockpile immunity in people, he argues. “Even if this particular threat” — the H5N1 outbreak in cows — “doesn’t turn into a pandemic, I do think it should give further impetus to really thinking about doing that,” he told STAT. But the idea of bundling H5N1 vaccine into the seasonal flu shot would cause regulatory challenges. The virus is not very immunogenic, meaning it doesn’t trigger a strong immune response in people. Research done nearly 20 years agoshowed that in order to achieve what would probably be a protective response, the vaccine would need to be given in two massive doses; later research showed two regular sized doses with an adjuvant, a compound that boosts the immune response a vaccine generates, would likely provide protection. Most seasonal flu shots do not contain an adjuvant — the sole exception is a vaccine for seniors sold by Seqirus, which contains the company’s MF-59 adjuvant. Adding an adjuvant to the seasonal shots would change the vaccines enough that new licenses might be needed — a big lift for manufacturers. In addition, studies would be needed to make sure that the H5N1 component did not erode the immune response to the other components of the vaccines. Zhang said that before H5N1 or another potential pandemic vaccine could be used in this way there would need to be more research. There’s no data, she noted, on what happens after repeated vaccination against H5N1. And it’s not clear when would be the best time to give it, because immunity induced by vaccination will wane over time. “All these, I think, are research questions that need to be addressed,” she said. If vaccinating people is such a tough call to make, why not just vaccinate the cows? This may turn out to be something that happens, but it’s still very early days. Some makers of animal vaccines are reportedly working on developing H5N1 vaccines for cows. But there are still a lot of questions that need answering before farmers are likely to embrace this approach, said Meghan Davis, a dairy and mixed animal veterinarian who does “One Health” research in Johns Hopkins University’s department of environmental health and engineering and school of medicine. (One Health is a term that refers to the intersection of human and animal health.) “I think we do not have enough information right now to address the really pragmatic questions that dairy producers are going to have, if they’re going to spend money for this,” Davis told STAT. Farmers will want to know who is going to pay for a vaccine that they may be mainly using to lower the risk that H5N1 will spill over from cows to people. Though animal vaccines can be much less expensive than the human equivalents, the price of the serum itself is not the only cost of an immunization program. If a vaccine has to be administered by a veterinarian, that adds to the cost. If it has to be given more than once, the cost goes up. Will all cows need it, or could you target only lactating cattle? How long will the immunity the vaccine induces last? “Without the answers to those questions, you really can’t think about your cost benefit at all,” she said. But Davis said farmers may see advantages of vaccination. The impact of H5N1 in cows is still coming into view because farmers have been pretty close-mouthed about what they are experiencing when the virus moves into a herd. However, word is starting to emerge that some of the affected cows do not return to pre-infection milk production levels, that when they recover from the infection some experience a “deficit,” Davis said. “Now you’ve got a cow who’s not going to produce as much as she would have produced at that point in her lactation.” In such cases, farmers may decide to send cows like these to slaughter earlier than otherwise would have been the case, getting fewer years of production out of these animals. If a vaccine prevented infection and protected against a drop in production, that might change the economics of the approach, she said. Another issue related to vaccination of animals against H5N1 relates to international trade. Though the World Organization for Animal Health — the animal equivalent of the World Health Organization — recommends against it, some countries restrict imports of poultry that have been vaccinated against avian influenza strains, because testing can’t easily differentiate between antibodies that are the result of previous infection or vaccination. Davis said this may be less of an issue for dairy cattle, as milk sales are more local and regional than international, but she noted it might be an issue for cheeses.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The case marks the first detection of the highly pathogenic strain of bird flu on the continent. Australia has reported its first human case of the H5N1 avian influenza in a child who recently returned from India. The case marks the first time the highly pathogenic strain of bird flu, which has killed millions of birds and mammals since it began circulating in 2020, has been detected on the continent. The child contracted the virus in India in March of this year - likely through contact with a sick bird - and experienced a “severe infection,” but has since made a full recovery, according to local health authorities. Officials said contact tracing has not identified any further infections and that the risk of transmission to others was “very low”, as the virus has not yet shown evidence that it can spread between people. The Department of Health in the Australian state of Victoria, where the human case was identified, are also responding to an outbreak of avian influenza at a poultry farm but has said that it is an unrelated incident. Although H5N1 infections in people are rare, the highly pathogenic virus carries an alarmingly high mortality rate. Of the 800 cases reported since the late 1990s, roughly 50 per cent resulted in death. The virus has recently broken out among dairy cattle in the US in an unprecedented outbreak. So far, 51 herds in nine US states have been affected, although experts think it is far more widespread. The apparent ability of the virus to spread between cows is significant because it provides more opportunities for it to evolve to better infect and spread between other mammals. Of particular concern is whether H5N1 might now be able to infect pigs, often described as ‘mixing vessels’ for influenza and making it more likely that the virus could adapt to spread between humans. So far this year, there have been two other confirmed human cases of H5N1. In Vietnam, a man died in March after direct contact with an infected bird, whilst in Texas a farm worker caught the virus from sick cattle – although his symptoms were mild. The US Centre for Disease Control is monitoring a further 300 people who have been exposed to the virus via cattle for signs of infection. The WHO still considers the risk to humans low but urged countries to rapidly share information to enable real-time monitoring of the situation to ensure preparedness as the virus continues to spread.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Scientists have found several strains of highly pathogenic avian influenza in a small number of NYC’s wild birds. A recent study has found a very small number of wild urban birds that either live in or migrate through New York City are carrying an unexpected hitchhiker: the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 (ref). This worrying discovery demonstrates that potentially serious human health risks are not limited to rural environments or to commercial factory farms as most people believe, but can also be found lurking in large cities. Thus, this study — the first of its kind — highlights the dangers of close contact between animals and humans because they may end up sharing infections — or even pandemics. “To my knowledge, this is the first large-scale U.S. study of avian influenza in an urban area, and the first with active community involvement,” the study’s senior author, microbiologist and geneticist Christine Marizzi, an Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said in a statement. Dr Marizzi also is the principal investigator of the New York City Virus Hunters (NYCVH) Program, and the director of community science at BioBus, which is an initiative to bring cutting-edge laboratory science to communities of students that have been historically underrepresented in science with the help of a converted school bus. Many migratory bird species stop over in New York City during their long journeys, which creates the ideal opportunity for different virus strains to meet and mix. “Birds are key to finding out which influenza and other avian viruses are circulating in the New York City area, as well as important for understanding which ones can be dangerous to both other birds and humans,” Dr Marizzi explained. “And we need more eyes on the ground — that’s why community involvement is really critical.” The findings were the result of a citizen scientist program to monitor the health of urban wild birds. Samples were collected by high school students in New York City who participate in both research and communication efforts as paid interns under Dr Marizzi’s expert mentorship. As part of their work, they’re provided with all the necessary protective gear to go out into the field and collect bird fecal samples, which they then help screen for viruses. Additional samples are also donated from local animal welfare centers, particularly the Wild Bird Fund, which is a local wild bird rescue. (Disclosure: I’ve been a $upporter of the Wild Bird Fund for many years.). To do this study, the junior scientist interns, or “Virus Hunters”, collected more than 2500 swabs and fecal samples in total from the Wild Bird Fund and from NYC’s parks and other natural areas across the boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx. The samples were then screened in a lab at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for the presence of two avian viruses: avian influenza and avian paramyxovirus. The Virus Hunters identified eight birds that were positive for avian paramyxovirus using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Two type 1 avian paramyxoviruses (APMV1, also known as Newcastle’s Disease Virus), were isolated from feral rock pigeons, Columba livia. These two viral isolates were named, reported to the USDA, and the whole genome sequences were published at the online data repository GenBank. APMV1 is a viral pathogen that affects pigeons and is present in most countries. It is a serious disease that can spread rapidly and cause high rates of pigeon illness and death. Other paramyxovirus strains may affect other avian species, particularly poultry. Between January 2022 and November 2023, the Virus Hunters continued their work by collecting 1927 samples from raptors, poultry and waterfowl (Figure 1). They screened these samples specifically for H5N1, also known as bird flu. They detected the virus in six city birds representing four different species: Canada geese, Branta canadensis; red-tailed hawks, Buteo jamaicensis; peregrine falcons, Falco peregrinus; and domestic chickens, Gallus gallus domesticus. The positive samples came from the urban wildlife rehabilitation centers, highlighting the critical role that such centers can play in viral surveillance. After comparing the genomic sequences of the samples to each other and to other H5N1 viral genomes available in GenBank, the Virus Hunters found they were a mix of the Eurasian H5N1 2.3.4.4.b clade and local North American avian influenza virus genotypes. Is New York City sitting on a ticking H5N1 pandemic time bomb? “It is important to mention that, because we found H5N1 in city birds, this does not signal the start of a human influenza pandemic,” Dr Marizzi cautioned. “We know that H5N1 has been around in New York City for about 2 years and there have been no human cases reported.” Currently, only one person has so far been infected by the H5N1 virus in the United States — a dairy worker in Texas. And yet despite the rarity of human H5N1 infections, this virus worries scientists that as bird flu spreads worldwide, the risk of it “jumping” the species barrier into humans continues to grow. For this reason, it’s important that people know what they can do to protect themselves from an infection with H5N1. “It’s smart to stay alert and stay away from wildlife,” Dr Marizzi advised. “This also includes preventing your pets from getting in close contact with wildlife.” Domestic cats are particularly susceptible. For example, out of 24 cats known to have contracted H5N1 on a single Texas dairy farm last month, twelve of them have died so far. If one must handle sick or injured birds or other wildlife, it is important to always use safe practices. These practices include placing a towel, blanket, jumper or pillowcase gently over the stricken animal. This will help keep it calm and aid with safe handling. If dealing with a sick or wounded bird, it is best to gently wrap it in a towel or hold the wings close to its body and place it into a paper bag or box for transport to bird rescue center. Research Published in Journal of Virology (May 15, 2024):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Avian influenza (serotype H5N1) is a highly pathogenic virus that emerged in domestic waterfowl in 1996. Over the past decade, zoonotic transmission to mammals, including humans, has been reported. Although human to human transmission is rare, infection has been fatal in nearly half of patients who have contracted the virus in past outbreaks. The increasing presence of the virus in domesticated animals raises substantial concerns that viral adaptation to immunologically naive humans may result in the next flu pandemic. Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) to track viruses was historically used to track polio and has recently been implemented for SARS-CoV2 monitoring during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, using an agnostic, hybrid-capture sequencing approach, we report the detection of H5N1 in wastewater in nine Texas cities, with a total catchment area population in the millions, over a two-month period from March 4th to April 25th, 2024. Sequencing reads uniquely aligning to H5N1 covered all eight genome segments, with best alignments to clade 2.3.4.4b. Notably, 19 of 23 monitored sites had at least one detection event, and the H5N1 serotype became dominant over seasonal influenza over time. A variant analysis suggests avian or bovine origin but other potential sources, especially humans, could not be excluded. We report the value of wastewater sequencing to track avian influenza. Preprint in medRxiv ( May 10, 2024): https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.05.10.24307179v1.full.pdf

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

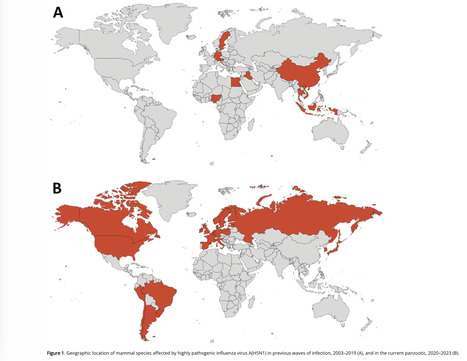

Sporadic human infections with highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) virus, with a wide spectrum of clinical severity and a cumulative case fatality of more than 50%, have been reported in 23 countries over more than 20 years. HPAI A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b viruses have spread widely among wild birds worldwide since 2020–2021, resulting in outbreaks in poultry and other animals. Recently, HPAI A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b viruses were identified in dairy cows, and in unpasteurized milk samples, in multiple U.S. states. We report a case of HPAI A(H5N1) virus infection in a dairy farm worker in Texas. In late March 2024, an adult dairy farm worker had onset of redness and discomfort in the right eye. On presentation that day, subconjunctival hemorrhage and thin, serous drainage were noted in the right eye. Vital signs were unremarkable, with normal respiratory effort and an oxygen saturation of 97% while the patient was breathing ambient air. Auscultation revealed clear lungs. There was no history of fever or feverishness, respiratory symptoms, changes in vision, or other symptoms. The worker reported no contact with sick or dead wild birds, poultry, or other animals but reported direct and close exposure to dairy cows that appeared to be well and with sick cows that showed the same signs of illness as cows at other dairy farms in the same area of northern Texas with confirmed HPAI A(H5N1) virus infection (e.g., decreased milk production, reduced appetite, lethargy, fever, and dehydration). The worker reported wearing gloves when working with cows but did not use any respiratory or eye protection. Conjunctival and nasopharyngeal swab specimens were obtained from the right eye for influenza testing. The results of real-time reverse-transcription–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) testing were presumptive for influenza A and A(H5) virus in both specimens. On the basis of a presumptive A(H5) result, home isolation was recommended, and oral oseltamivir (75 mg twice daily for 5 days) was provided for treatment of the worker and for postexposure prophylaxis for the worker’s household contacts (at the same dose). The next day, the worker reported no symptoms except discomfort in both eyes; reevaluation revealed subconjunctival hemorrhage in both eyes, with no visual impairment. Over the subsequent days, the worker reported resolution of conjunctivitis without respiratory symptoms, and household contacts remained well.... Published in NEJM (May 3, 2024):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The USDA tested 30 samples from states with herds infected by H5N1. Tests of ground beef purchased at retail stores have been negative for bird flu so far, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced Wednesday, after studying meat samples collected from states with herds infected by this year's unprecedented outbreak of the virus in cattle. The results "reaffirm that the meat supply is safe," the department said in a statement published late Wednesday after the testing was completed. Health authorities have cited the "rigorous meat inspection process" overseen by the department's Food Safety Inspection Service, or FSIS, when questioned about whether this year's outbreak in dairy cattle might also threaten meat eaters. "FSIS inspects each animal before slaughter, and all cattle carcasses must pass inspection after slaughter and be determined to be fit to enter the human food supply," the department said. The National Veterinary Services Laboratories tested 30 samples of ground beef in total, which were purchased at retail outlets in states with dairy cattle herds that had tested positive. To date, dairy cattle in at least nine states — Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Michigan, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota and Texas — have tested positive for H5N1, which is often lethal to poultry and other animals, like cats, but has largely spared cattle aside from sometimes disrupting their production of milk for a few weeks. A USDA spokesperson said the ground beef they tested came from stores in only eight of those states. Colorado was only confirmed to have H5N1 in a dairy cow after USDA had collected the samples. The spokesperson did not comment on whether beef from stores in additional states would be sampled. More results from the department related to bird flu in beef are expected soon. Samples collected from the beef muscle of dairy cows condemned by inspectors at slaughter facilities are still being tested for the virus. The department is also testing how cooking beef patties to different temperatures will kill off the virus. "I want to emphasize, we are pretty sure that the meat supply is safe. We're doing this just to enhance our scientific knowledge, to make sure that we have additional data points to make that statement," Dr. Jose Emilio Esteban, USDA under secretary for food safety, told reporters Wednesday. The studies come after the USDA ramped up testing requirements on dairy cattle moving across state lines last month in response to the outbreak. Officials said that was in part because it had detected a mutated version of H5N1 in the lung tissue of an asymptomatic cow that had been sent to slaughter. While the cow was blocked from entering the food supply by FSIS, officials suggested the "isolated" incident raised questions about how the virus was spreading. Signs of bird flu have also made its way into the retail dairy supply, with as many as one in five samples of milk coming back positive in a nationwide Food and Drug Administration survey. The FDA has chalked those up to harmless fragments of the virus left over after pasteurization, pointing to experiments showing that there was no live infectious virus in the samples of products like milk and sour cream that had initially tested positive. But the discovery has worried health authorities and experts that cows could be flying under the radar without symptoms, given farms are supposed to be throwing away milk from sick cows. One herd that tested positive in North Carolina remains asymptomatic and is still actively producing milk, a spokesperson for the state's Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services told CBS News. It remains unclear how H5N1 has ended up in the milk supply. Don Prater, the FDA's top food safety official, said Wednesday that milk processors "can receive milk from hundreds of different farms, which may cross state lines," complicating efforts to trace back the virus. "This would take extensive testing to trace it that far," Bailee Woolstenhulme, a spokesperson for the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food, told CBS News. Woolstenhulme said health authorities are only able to easily trace back milk to so-called "bulk tanks" that bottlers get. "These bulk tanks include milk from multiple dairies, so we would have to test cows from all of the dairies whose milk was in the bulk tank," Woolstenhulme said.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Virus has already killed other mammals including sea lions and seals, while also taking toll on farm animals. The first case of a walrus dying from bird flu has been detected on one of Norway’s Arctic islands, a researcher has said. The walrus was found last year on Hopen island in the Svalbard archipelago, Christian Lydersen, of the Norwegian Polar Institute, told AFP. Tests carried out by a German laboratory revealed the presence of bird flu, Lydersen said. The sample was too small to determine whether it was the H5N1 or the H5N8 strain. “It is the first time that bird flu has been recorded in a walrus,” Lydersen said. About six dead walrus were found last year in the Svalbard islands, about 1,000km (620 miles) from the north pole and halfway between mainland Norway and the north pole.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

In early March, veterinarian Barb Petersen noticed the dairy cows she cared for on a Texas farm looked sick and produced less milk, and that it was off-color and thick. Birds and cats on the farm were dying, too. Petersen contacted Kay Russo at Novonesis, a company that helps farms keep their animals healthy and productive. “I said, you know, I may sound like a crazy, tinfoil hat–wearing person,” Russo, also a veterinarian, recalled at a 5 April public talk sponsored by her company. “But this sounds a bit like influenza to me.” She was right, as Petersen and Russo soon learned. On 19 March, birds on the Texas farm tested positive for H5N1, the highly pathogenic avian flu that has been devastating poultry and wild birds around the world for more than 2 years. Two days later, tests of cow milk and cats came back positive for the same virus, designated 2.3.4.4b. “I was at Target with my kids, and a series of expletives came out of my mouth,” Russo said. Now, 3 weeks into the first ever outbreak of a bird flu virus in dairy cattle, Russo and others are still dismayed—this time by the many questions that remain about the infections and the threat they may pose to livestock and people, and by the federal response. Eight U.S. states have reported infected cows, but government scientists have released few details about how the virus is spreading. In the face of mounting criticism about sharing little genetic data—which could indicate how the virus is changing and its potential for further spread—the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) did an unusual Sunday evening dump on 21 April of 202 sequences from cattle into a public database. (Some may be different samples from the same animal.) And despite public reassurances about the safety of the country’s milk supply, officials have yet to provide supporting data. The cow infections, first confirmed by USDA on 25 March, were “a bit of an inconvenient truth,” Russo says. Taking and testing samples, sequencing viruses, and running experiments can take days, if not weeks, she acknowledges. But she thinks that although officials are trying to protect the public, they are also hesitant to cause undue harm to the dairy and beef industries. “There is a fine line of respecting the market, but also allowing for the work to be done from a scientific perspective,” Russo says. Only one human case linked to cattle has been confirmed to date, and symptoms were limited to conjunctivitis, also known as pink eye. But Russo and many other vets have heard anecdotes about workers who have pink eye and other symptoms—including fever, cough, and lethargy—and do not want to be tested or seen by doctors. James Lowe, a researcher who specializes in pig influenza viruses, says policies for monitoring exposed people vary greatly between states. “I believe there are probably lots of human cases,” he says, noting that most likely are asymptomatic. Russo says she is heartened that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has “really started to mobilize and do the right thing,” including linking with state and local health departments, as well as vets, to monitor the health of workers on affected farms. As farms in more states began to report infected dairy cows last month, one theory held migratory birds were carrying the virus across the country and introducing it repeatedly to different dairy herds. But Lowe dismisses the idea as “some fanciful thinking by some cow veterinarians and some cow producers” who hoped to “protect the industry.” Richard Webby, an avian influenza researcher at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, notes that available data on the virus’ genetic sequence show “no smoking guns”—mutations that could enable it to jump readily from birds to cows. At a 4 April meeting organized by a group known as the Global Framework for the Progressive Control of Transboundary Animal Diseases, Suelee Robbe Austerman of USDA’s National Veterinary Services Laboratory said “a single spillover event or a couple of very closely related spillover events” from birds is more likely. The cow virus—which USDA has designated 3.13—could then have moved between farms as southern herds were moved northward for the spring, perhaps spreading from animal to animal on milking equipment. Lowe notes that researchers at Iowa State necropsied infected cows and found no virus in their respiratory tracts, which could enable spread through the air. USDA considers H5N1 in poultry a “program disease,” which means it is foreign to the country and subject to regulations to control it. But the agency has made no such determination for the cow disease, which means the federal government has no power to restrict movement of cattle or to require testing and reporting of infected herds or of the humans who work with them. As a result, confusion is rife. A knowledgeable source who asked not to be identified says cattle that were healthy when they left a Texas farm appear to have brought the virus to a North Carolina farm. That raises the possibility that many cattle are infected but asymptomatic, which would make the virus harder to contain. Evidence suggests it has spread from cattle back to poultry, USDA says. Another source told Sciencenone that birds tested positive for the 3.13 strain and were culled at a Minnesota turkey farm right next to a dairy farm that refused to test its cattle. The industry and veterinarians bear some responsibility for the confusion, Lowe says. “We didn’t even try to get ahead of this thing,” he says. “That’s a black mark on the industry and on the profession.” Webby also faults USDA for not releasing data more quickly. The agency made six sequences from cattle—plus six related ones from birds and one from a skunk—available on the GISAID database on 29 March, 1 week after learning that cows were infected. It released one more sequence on 5 April, but then shared nothing else until the data dump 16 days later. Webby suspects the agency has moved cautiously because of the potential impact on the dairy industry. “There are a lot of people who are vested in this, and their livelihoods, at least on paper, can be impacted by whatever is found.” Thijs Kuiken, an avian influenza researcher at Erasmus Medical Center, says the “very sparse” information released by the U.S. government has international implications, too. State and federal animal health authorities have “abundant information … that [has] not been made public, but would be informative for health professionals and scientists” in the United States and abroad, he says, “to be able to better assess the outbreak and take measures, both for animal health and for human health.” He notes that even the new sequences released by USDA do not include locations of the samples or the date they were taken. USDA said in a statement to Sciencenone that it will continue “to provide timely and accurate updates” and that its staff “are working around the clock” on a thorough epidemiological investigation to determine routes of transmission and help control spread. With its Sunday evening release, USDA made the unusual move to bypass GISAID—which requires a login and restricts how data can be used—and instead posted on a database run by the National Institutes of Health that everyone can access and do with as they please. USDA explained it did this “in the interest of public transparency and ensuring the scientific community has access to this information as quickly as possible to encourage disease research.” The dairy industry is particularly worried that sales could suffer because of unwarranted fears that milk might infect people with the virus. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has said it has “no concern” that pasteurized milk presents risks because the process “has continually proven to inactivate bacteria and viruses, like influenza, in milk.” But Lowe says for this specific virus, there are no data to back that claim. That’s “shocking,” he says. “It should not be that hard to get that data. I do not know why the foot dragging is occurring there.” In a statement to Sciencenone, FDA said the agency is working to “reinforce our current assessment that the commercial milk supply is safe” and will share data as soon as possible. “U.S. government partners are working with all deliberate speed on a wide range of studies looking at milk along all stages of production, including on the farm, during processing and on shelves,” the statement said. Daniel Perez, an influenza researcher at the University of Georgia, is doing his own test tube study of pasteurization of milk spiked with a different avian influenza virus. The fragile lipid envelope surrounding influenza viruses should make them vulnerable, he says. Still, he wonders whether the commonly used “high temperature, short time” pasteurization, which heats milk to about 72°C for 15 or 20 seconds, is enough to inactivate all the virus in a sample. Lowe predicts that with increased safety precautions at farms, including more rigorous cleaning of milking equipment, and the end to the seasonal movement of cattle, this outbreak likely will die out—as often happens when bird influenza viruses infect mammals that do not make particularly good hosts. But he and other researchers say to truly assess the continuing threat of H5N1 in cattle, they need to understand how this virus succeeded at infecting dairy cows in the first place. “Which cells is the virus replicating in? How is it getting around the body? What receptor is it using to get into cells?” Lowe wonders. “Those are the really interesting questions.” Correction, 23 April 2024, 7:35 a.m.: A previous version of this story said James Lowe necropsied infected cows. He didn't but noted that researchers at Iowa State University did.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

As the virus continues its spread to new species, the World Health Organization fears it is moving closer to people. The risk of bird flu jumping into humans is of “enormous concern,” the World Health Organization has warned as the virus continues its spread into new species. Since 2020, an outbreak of the H5N1 strain has killed tens of millions of birds worldwide, along with thousands of mammals, including sea lions, elephant seals and even one polar bear. More recently, the virus emerged in 16 herds of cattle in Texas – a development which has surprised experts, as it was previously believed the animals were not susceptible to infection, and raised concerns that H5N1 could eventually spill over into humans. “This remains, I think, an enormous concern,” Dr Jeremy Farrar, the WHO’s chief scientist, told reporters on Thursday in Geneva. “When you come into the mammalian population, then you’re getting closer to humans … this virus is just looking for new, novel hosts.” He warned that, by circulating in new mammals, the virus improves its chances of further evolving and developing “the ability to infect humans and then critically the ability to go from human to human”. In the recent cattle outbreak in Texas, one person was diagnosed with bird flu following close contact with dairy cows presumed to have been infected. Over the past 20 years, hundreds of others have caught the virus following exposure to an infected animal – yet there has been no evidence of human-to-human transmission in these cases. Yet the mortality rate for humans is “extraordinarily high,” Dr Farrar warned. From 2003 to 2024, 463 deaths and 889 cases were reported from 23 countries, according to the WHO – a case fatality rate of 52 per cent. The Texas infection is the second case of bird flu in the US and appears to have been the first infection of the H5N1 strain through contact with an infected mammal, said the WHO. Dr Farrar said the ongoing bird flu outbreak had become “a global zoonotic animal pandemic” and called for increased monitoring, adding that it was “very important” to understand how many human infections are occuring “because that’s where adaptation [of the virus] will happen”. He added: “It’s a tragic thing to say, but if I get infected with H5N1 and I die, that’s the end of it. If I go around the community and I spread it to somebody else then you start the cycle.” He said efforts were being made to develop vaccines and therapeutics for the strain and stressed the importance of international health authorities having the capacity to diagnose the virus. This would ensure that the world would be “in a position to immediately respond” if the strain “did come across to humans, with human-to-human transmission”, said Dr Farrar.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|